A new book aims to defend Sayyed Qutb, but the rapid collapse of Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood government is yet another demonstration that his philosophies are no alternative to modernity.

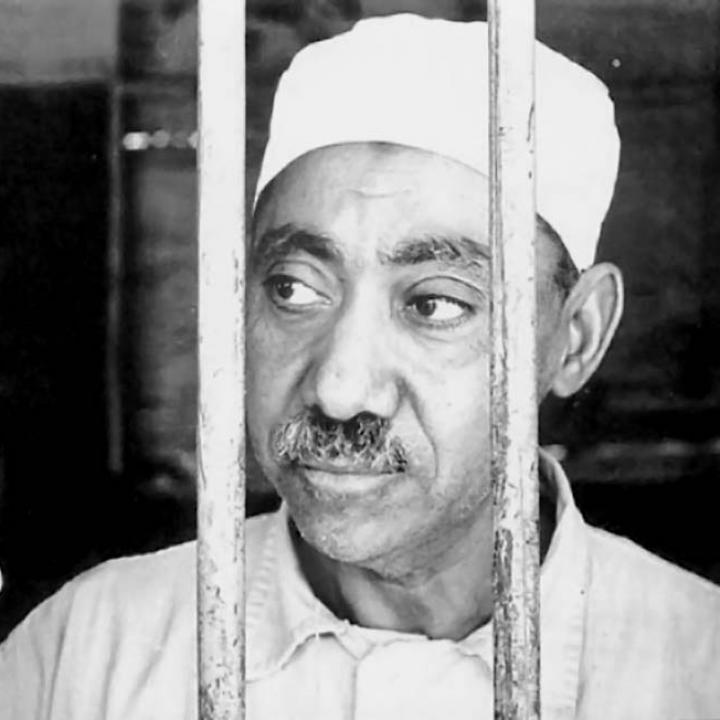

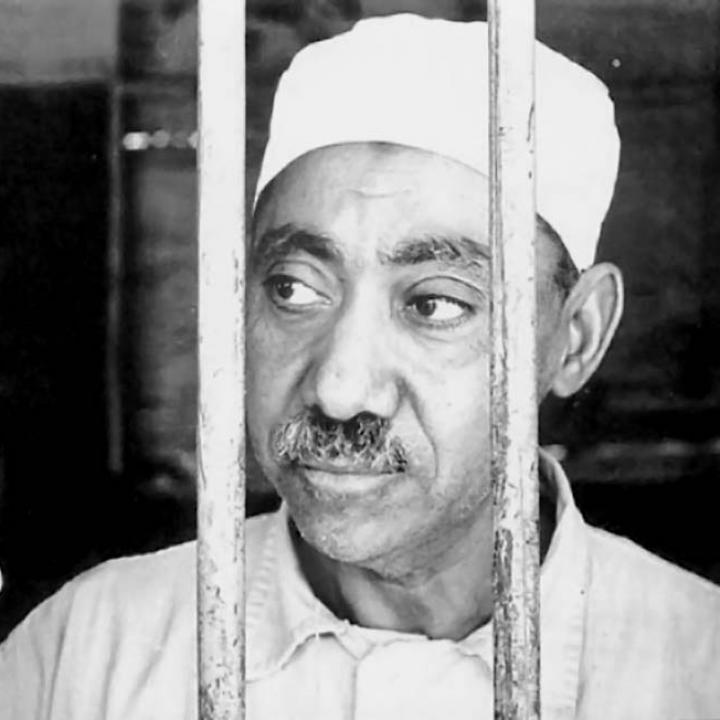

Sayyid Qutb was an Egyptian educator, writer and literary critic. He was also a founding theorist of jihadism and one of the few intellectuals that Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood has produced in its 85-year history. Qutb's ideas shaped the uncompromising approach to governance that led to Mohammed Morsi's recent ouster.

Born in the Egyptian village of Musha in the southern governorate of Asyut in 1906, Qutb was raised in a religious, politically active home with strong nationalist tendencies. He was educated at Dar al-Ulum in Cairo, the same university that Muslim Brotherhood founder Hassan al-Banna had attended, and he worked as a teacher for the Ministry of Education after graduating in 1933. Qutb, who had reportedly memorized the Quran by the age of 10, initially took to the secular culture of Cairo's literary scene. But then he spurned both democracy and secularism, embracing instead a zealous moralism.

In 1950, after spending two years in the U.S. on a government scholarship, Qutb returned to Egypt. His antagonism toward the West had hardened. America, and indeed much of the Arab world, embodied what he called jahiliyya, a Quranic term that connotes apostasy, immorality and evil. Thoroughly radicalized, he formally joined the Muslim Brotherhood in 1953. A year later he was arrested, along with other Brotherhood members, during Gamal Abdel Nasser's crackdown on the group. For the next 12 years, until his execution in 1966, Qutb slid further toward militancy, formulating his distinctive brand of Islamism, which advocates violently toppling non-Islamic governments and replacing them with puritanical Muslim theocracies. His life and voluminous writings have inspired generations of terrorists, including al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, whose own writings frequently quote Qutb.

But anthropologist James Toth thinks Qutb wasn't all that bad. In "Sayyid Qutb: The Life and Legacy of a Radical Islamic Intellectual," Mr. Toth generously casts his subject as a "complicated" figure whose religious beliefs were "reasoned" and "credible." He dismisses the common portrayal of Qutb, in which he is "totally consumed by hatred for the West," as an "Orientalist" trope to rally public opinion against Islamism. He insists that Qutb's vision constitutes "a viable alternative to a Western-derived modernity."

It's a bold but unpersuasive argument. Mr. Toth mistakes the internal logic of Qutb's writings for reason and fails to note that they rest on a series of bigoted premises. He claims that the West caricatures Qutb to justify its supposedly hawkish ambitions in the Middle East when, in fact, the opposite is true: It was Qutb who called his readers to arms based on a caricature of the West. And Mr. Toth ignores radical Islam's record of social brutality and economic failure, which hardly makes it a "viable alternative" to modernity -- unless, that is, it's underwritten by substantial oil wealth.

The author aims to analyze Qutb's ideas without "in any way judging" them. The picture of Qutb that nevertheless emerges isn't pretty. Mr. Toth concedes that Qutb was an "unabashed adherent of patriarchy" and had a profound hatred of Christians and Jews, against whom Qutb declared jihad because they "distorted God's word and deviated from God's path." Qutb also raged against "errant Muslims," who, he said, should likewise be targeted for violence because they are "domestic enemies."

Qutb's ultimate goal was imposing a very controlling interpretation of Shariah, or Islamic law, which he said can be applied to "all aspects of life." He sanctified violence against the protectors of the non-Islamic status quo. Under Qutb's preferred political system, people would swear an oath to a "just ruler," whose sole purpose is enforcing the divine law. Qutb opposed the establishment of legislatures, which he believed couldn't legitimately "overturn or vote out sacred laws." Mr. Toth is coy about all of this. "Qutb was not a democrat," he writes.

The author offers the stock account of Qutb's biography. He relies almost exclusively on secondary sources and argues that Nasser's repression catalyzed Qutb's conversion from "moderate Islamist" to "radical Islamist." He rightly points to Qutb's 1964 book "Signposts on the Road" -- in which, according to Mr. Toth, Qutb "directed his troops to go out and smite evil and propagate the good" so as to replace modernity with "true Islam" -- as the capstone of Qutb's radicalism. He contrasts this "call to battle" with Qutb's earlier, supposedly "moderate," works, such as "Social Justice in Islam" (1949), which presented Islamism as a movement for achieving greater societal equality.

Yet there is continuity between Qutb's earlier "moderate" and later "radical" Islamism. During both periods, implementing Qutb's ideas required violence: How else to enforce a ban on coed beach bathing, or to criminalize songs that "corrupted the virtues of men and women," as Qutb advocated during his so-called moderate years? Indeed, the repressiveness of Qutb's allegedly moderate Islamism differs primarily in scale from the global terrorism that his radical Islamism inspired.

Western policy makers and intellectuals for too long have refused to see that "radical" and "moderate" Islamism, while not equally violent, both produce tyranny. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the West feared that writing off Islamism entirely would mean alienating the Muslim world. But the resulting approach, which attempted to boost "moderate" Islamists over the "radicals," wasn't just an exercise in self-delusion: It meant missing opportunities to support anti-Islamist Muslims when they rose up against Islamist dictators, as we have seen this year in Egypt and Turkey.

The rapid collapse earlier this month of Egypt's Brotherhood regime demonstrates that Qutb's philosophy isn't an alternative to modernity. It's the opposite of modernity, better known as backwardness. The Muslim world deserves better.

Eric Trager is a Next Generation fellow at The Washington Institute.

Wall Street Journal