When the next President enters office, Iran will be a nuclear-weapons threshold state operating more than 5,000 centrifuges, with more than 14,000 additional ones at hand but deactivated—assuming the July 14 accord is implemented and survives its infancy. It will be openly engaged in research and development on advanced centrifuges. Its heavy water reactor and its underground second enrichment facility will both be modified but otherwise intact and in use. Iran will have successfully defied multiple UN Security Council resolutions by refusing to suspend uranium enrichment, to dismantle illicitly built nuclear infrastructure, and to make a full declaration regarding its past clandestine nuclear activities or fully address IAEA inquiries about them.

Iran will also possess a large, sophisticated ballistic missile arsenal, face no ban on the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles, and will be relieved of sanctions against its missile efforts by 2023 regardless of its actual missile activities. Its regional influence will have expanded, and its support for terrorism will likely continue unabated, benefited by Iran’s influx of financial resources and the prospective lifting of sanctions against its export of conventional arms in 2020 and selective de-designations of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force and its commanders.

Iran will not be free of all sanctions, but it will have shed the most significant and restrictive ones, allowing it to grow economically and expand its influence diplomatically and militarily. A major divide will linger between the United States and its closest regional allies over perceived U.S. diffidence in the face of Iranian assertiveness, further eroding a U.S.-led security architecture already reeling from the Iraq War, the Arab uprisings, and subsequent American disengagement from an active role in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere.

It might be tempting to regard these developments as regrettable but peripheral to America’s global foreign policy agenda as Asia and Russia loom larger as concerns. Some may regard it as an acceptable price for deferring a long-running confrontation between Tehran and Washington over Iran’s nuclear ambitions. But the truth is that Iran poses a challenge to vital U.S. interests in the Middle East: nonproliferation, counterterrorism, the freedom of navigation in key waterways such as the Strait of Hormuz, cyber security, and others. Iran’s strategy for advancing its own objectives clashes with America’s strategy for advancing its interests, which aims to ensure regional stability, provide for the security of Israel and other allies, weaken violent non-state actors, and prevent the rise of any hegemon from within the region or without.

The next President will thus inherit not only a nuclear accord that was opposed by majorities of congress and the American public, but a broader policy that her or she regardless of party affiliation will find insufficient to meet the challenges the U.S. faces with respect to Iran and the Middle East. As part of a broader comprehensive strategy to rebuild American alliances, advance U.S. interests, and improve stability and security in the region, the next Administration should devise an Iran policy focused on re-establishing American deterrence, strengthening constraints on Tehran’s nuclear program, countering Iranian efforts to project power regionally, and increasing pressure on the regime. The next President will be doing so in a more difficult international and regional environment and with fewer tools at the ready compared to predecessors.

Mike Singh on Iran and its Regional Ambitions from The John Hay Inititative on Vimeo.

The Obama Administration’s Iran policy has boiled down to a double gamble: first, that striking an agreement with Tehran that relieved sanctions while leaving it with an extensive nuclear weapons capability was better than the available alternatives; and second, that U.S. overtures and security assurances, together with the time bought by the agreement, could see Iran transformed into a more benevolent regional power whose threat to the United States and its allies is diminished. The challenge for the next President is that he or she will not know upon assuming office, or perhaps even over the full four to eight years of his or her tenure, whether President Obama’s gambles will ultimately pay off. Nor will the next Administration have the luxury of waiting to see the nuclear bargain’s impact on Iran’s long-term internal dynamics, because it seems more likely that Iranian behavior will worsen rather than improve in the short-to-medium-term, and that the regime will strengthen its hold on power.

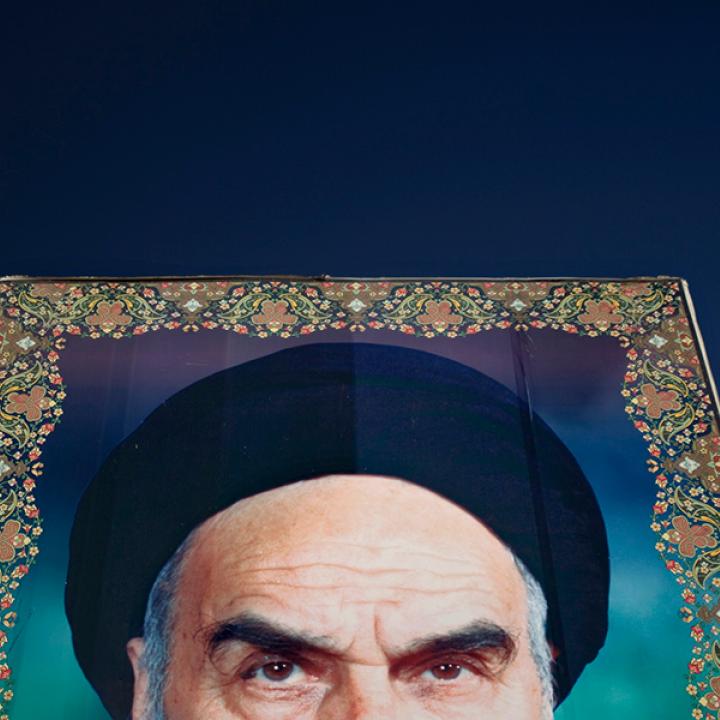

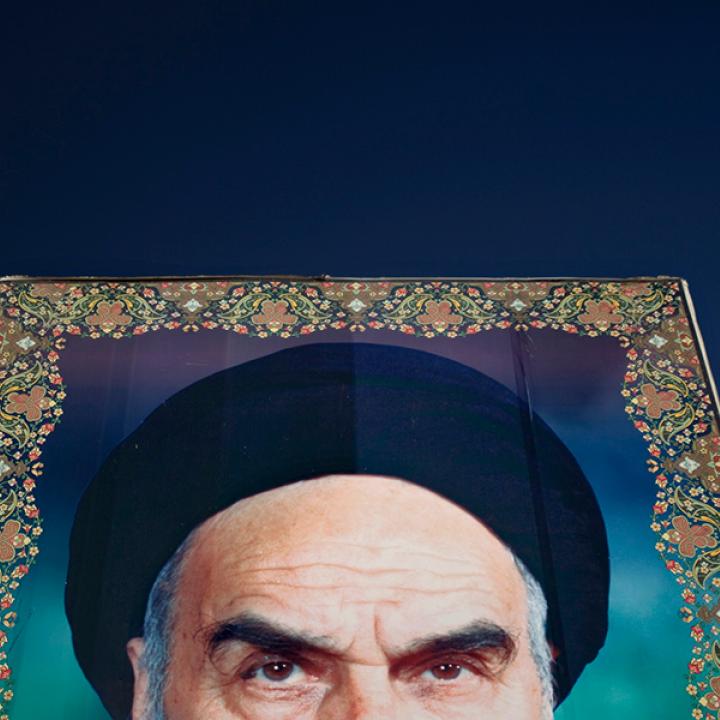

Anti-Americanism is one of the founding pillars of Iran’s Islamic regime, and Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei may feel the need to reassert his fidelity to it following his nuclear compromise with Washington. He may also be wary that the agreement will disproportionately benefit President Hassan Rouhani and his pragmatic faction and thus take steps to strengthen Rouhani’s hardline opponents to prevent the political balance he assiduously seeks to maintain from being disturbed. As Secretary of State John Kerry has noted, the deal was done over the objections of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and the Guards are unlikely to slip quietly into the Iranian night.

Furthermore, Iranian regional behavior is not driven only by the policy choices of the United States or by nuclear diplomacy but also by events in the region. Iran’s security strategy hinges on projecting power well beyond its borders while seeking to create an inhospitable security environment for the United States and its allies. To advance this strategy, Iran has cultivated impressive asymmetric capabilities to compensate for its conventional military weakness, primarily by building, training, arming, and funding proxies and allies such as Hizballah, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and Shi'a militias in Iraq and Syria. It has in a sense similarly instrumentalized the Syrian regime, which is vital to Iran’s ability to project power in the Levant and coordinate with its proxies there. Iran has thus invested significant effort and resources in propping the Assad regime up. Tehran has also built a rudimentary but nevertheless serious anti-access/area denial (A2AD) capability with sea mines, fast boats, offensive cyber capabilities, and an extensive missile arsenal, among other things.

Because the regional situation is growing more chaotic and the chaos is unlikely to soon abate, and since Iran shows no sign of reconsidering its regional interests or strategy for advancing them, its destabilizing activities are likely to wax rather than wane. Iran’s activities in turn draw a response from U.S. allies in the region, who are increasingly assertive as a result of American disengagement. The consequent dynamic will likely feed a vicious cycle of unresolved conflict spreading. That cycle may well include efforts by U.S. regional allies to develop their own nuclear programs to match Iran’s status as a nuclear weapons threshold state, in order to ensure their ability to respond in kind to any quick Iranian nuclear breakout.

Furthermore, Iran’s nuclear efforts should not be considered separate from its regional strategy but part of it; if Iran’s strategy remains unchanged, its nuclear weapons ambitions should also be expected to linger. Nuclear weapons would add a strategic element to Iran’s existing asymmetric deterrent, bolster the regime’s domestic security, and ensure that external adversaries’ freedom to respond to Iranian and Iranian-sponsored attacks and subversion is limited. Relative freedom from effective countermeasures, in turn, would provide Iran an incentive to increase such activities.

Iran will not only have a strong incentive to develop nuclear weapons, but the nuclear agreement will also leave it with the capability to do so. Indeed, that capability will grow rather than diminish over the agreement’s duration as the restrictions on Iranian nuclear activities phase out. Even assuming Iran does not withdraw from the arrangement sooner, after 15 years Iran will face no restrictions on enriching uranium above 3.67 percent (90 percent is generally regarded as weapons-grade), and will begin deploying advanced centrifuges that can enrich uranium many times as efficiently as its existing machines after eight and a half years have passed. Iran will also have far more resources to pursue these and other goals: Limits on its oil exports will have been removed, international investment in expanding its hydrocarbon production will be unfettered, and oil prices are likely to be above their unusually low 2014-15 levels.

While Iran’s nuclear weapons capability will grow, the tools available to the United States to counter and contain it will be diminished. Iran’s growing nuclear activities and its remaining nuclear infrastructure will have been granted legitimacy by the international community, its defensive and offensive military capabilities will be greater, and the United States will have agreed not only to refrain from imposing additional sanctions on Iran for nuclear advances but will also have suspended its most significant sanctions. A military strike, in addition to its other downsides, will be increasingly complicated due to international involvement in Iranian nuclear activities and foreign investment in Iran's key economic sectors, such as hydrocarbons. To avoid the twin debilities of simple acquiescence to Iranian nuclear and regional activities or increasing reliance on military or other direct action to deter or reverse them, new strategies and tools will be needed.

While much of the focus in advance of January 2017 will be on the nuclear agreement, the next Administration will require—as a result of the situation it will inherit—an entirely new Iran strategy. Such an approach will require a broad policy review that assesses the state of Iran’s nuclear activities, its regional activities, the broad situation in the Middle East, and the stances of key U.S. allies in the region and beyond. Such a review should nest discrete questions such as how to handle the nuclear issue and how to counter Iranian regional behavior into broader assessment of the challenges Iran poses to U.S. interests and objectives. It should be devised in partnership with Congress, taking into account the congressional and public concerns expressed during the review of the JCPOA and any subsequent congressional actions. It should produce a strategy for countering those challenges and improving U.S. tools for implementing it–this in the context of a comprehensive Middle East strategy that takes into account extant realities and broader U.S. foreign policy goals.

On the critical question of Iranian nuclear proliferation, the next President should make clear that the aim of American policy is not only to prevent Iran from possessing an actual nuclear weapon, but to prevent it from having an exercisable nuclear weapon capability. The nuclear accord of July 14, 2015, is insufficient to reliably prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon covertly and expires entirely in a phased manner between 2020 and 2030, giving rise to the possibility that Iran could “break out” quickly even at declared sites (albeit in contravention of its international obligations).

In light of these and other serious deficiencies, the next Administration will undoubtedly look to strengthen nuclear constraints on Iran and will wish to do so in partnership with key allies in Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and elsewhere. Indeed, given the expiration of nuclear restrictions on Iran in relatively short order, the U.S. debate will not be whether the strengthening of these constraints is required, but how to accomplish it.

Strengthening the nuclear constraints on Iran will be complicated by the Obama Administration’s support for the 2015 accord and the subsequent UN Security Council resolution enshrining it. These decisions are not binding on the next President and in fact offer a mechanism to unwind the accord and reimpose U.S. and international sanctions whenever the next President desires to do so. However, President Obama’s decisions will make it harder for his successor to gain allied support for measures necessary to deter the expansion of Iran’s nuclear program. Doing so will be easier if the next Administration develops an early and specific concept of what additional constraints it seeks; the Administration should therefore consider focusing especially on the failure to address Iran’s past weaponization activities, the weakness of the IAEA inspection regime for suspect sites, the automatic sunset of its restrictions, and its lifting of non-nuclear sanctions without imposing limitations in non-nuclear areas (such as ballistic missile development) on Iran.

Even as it seeks to strengthen the constraints on Iran’s nuclear program, the next Administration must deter Iranian nuclear-related activity neglected entirely or even facilitated under the accord, such as advanced ballistic missile activities, and take steps to deter a covert Iranian breakout attempt. The next President should consider a broader spectrum of options to deter Iran’s development of nuclear-capable ICBMs and reentry vehicles and respond to other egregious Iranian behavior, and make public its readiness to use force if necessary.

With regard to Iran’s regional policy, U.S. allies in the Mideast are arguably more concerned about Iranian destabilization and subversion of neighbors than they are about its nuclear program. Here, the next President’s room for maneuver will be greater, as neither Iran nor the United States made any commitments in this area in the nuclear accord. The need for action will also be great, given the Obama Administration’s relative inaction and the likelihood that Iran’s destabilizing activities will increase.

Two lines of action are required. First, the U.S. government and those of its allies must impose costs on Iran for its destabilizing regional activities. This should include blocking the flow of Iranian material and financial assistance to proxies, actions against those proxies themselves (for example, designating them under relevant sanctions laws where this has not already been done), countering Iranian efforts to harass commercial shipping and naval vessels in the Gulf, and responding to Iranian cyber threats and attacks. The U.S. will also need to develop tools and strategies to counter Iranian A2AD efforts, which are likely to increase in the wake of the nuclear accord. To be credible, this should be done in the context of an overall increase in defense spending.

In addition, nothing prevents the United States and its allies from ramping up sanctions on Iran in response to its destabilizing regional activities. Indeed, such actions could reinstate some of the pressure alleviated by the lifting of nuclear sanctions. While U.S. allies in Europe and elsewhere may prove initially reluctant to support such steps, a strong case can be made that their interests are undermined by Iran’s contribution to Middle East instability, especially in Syria and Iraq. Such sanctions and designations may also induce caution within the international business community about reengaging in Iran, for the same reasons they withdrew during the past decade: the reputational risk of doing business with entities engaged in illicit activities.

Efforts to counter Iran would be immeasurably strengthened by changes to U.S. strategy in Syria, by increasing pressure on the Assad regime, and, in Iraq, by sidelining Iranian proxies and IRGC forces and preventing Shi'a militias from becoming institutionalized, as they have been in Lebanon and in Iran itself. In contrast, U.S. strategy may be hampered by what are likely to be growing relationships between Iran on the one hand and Russia and China, among others, on the other. The next Administration should use the tools available to it to ensure that these relationships do not fuel additional destabilizing Iranian policies.

Second, the U.S. government should strengthen its regional allies and improve its coordination with them. This will mean strengthening the bonds of the alliances themselves, as well as strengthening the capabilities of each of our allies to better counter Iranian mischief. One of Iran’s chief advantages in Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere is the simple fact that the United States and its allies are not on the same page strategically and thus do not coordinate effectively. At the same time, greater attention should be paid to strengthening vulnerable governments, especially those of Lebanon and Jordan.

Regardless of whether Iran is complying with the nuclear agreement or expanding its destabilizing regional behavior, the next President should also seek effective ways to support human rights in Iran, and to demonstrate American sympathy with political reformers. This will be most effective as an international rather than a unilateral effort and should encompass the development of technological tools that could assist dissidents globally, advance action on Iranian human rights abuse in international forums, and demonstrate other forms of international support for activists. This should be done in recognition that a true resolution of international concerns with Iranian policy is likely only to follow a broader political shift within Iran itself, albeit one that only Iranians can bring about.

A final question the next President will have to confront will be whether to engage with Iran. Engagement is a tool, not a strategy. The U.S. government should continue to use engagement on a case-by-case basis, as it uses any other tactic in its foreign policy toolkit, in coordination with allies, and in support of the objectives described above. Engagement should be thought of not as an Obama Administration policy, because in reality the U.S. government has selectively engaged with Iran for decades under Presidents Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Clinton, and George W. Bush. Crucially, the U.S. government should broaden its engagement beyond the handful of officials dispatched by the Iranian regime to the nuclear negotiations to include other segments of Iranian society that may have a greater interest in better relations with the United States. Even as the United States and its allies seek to counter destabilizing Iranian behavior, the door should be left open should Iran choose finally to undertake a strategic shift—but the shift must be Tehran’s, not Washington’s.

The next President is likely to inherit an Iran policy with which he or she is dissatisfied—not only an overly generous nuclear accord, but also a record of relative inaction against Iran’s expanding regional activities and on questions of human rights. Countering Iran in the wake of the nuclear accord will be a challenging and complicated task. International consensus may prove elusive, and the U.S. government will have sacrificed many of its most effective tools of pressure. But it is a task than cannot be shirked. It should be pursued with an eye not only to thwarting the threats Iran poses to U.S. interests, but also as part of the sort of comprehensive strategy toward the Middle East that has been absent in recent years, one that takes care to not only preserve but to enhance American influence and leadership globally.

John Hay Institute