The threat of decertifying the nuclear deal gives the administration an opening with those who wish to preserve it, so the president should use this leverage wisely rather than taking an all-or-nothing approach.

Read Part 1 of this PolicyWatch, which outlines the five decisions the Trump administration needs to make in deciding the JCPOA's fate.

As President Trump prepares to deliver a major Iran policy address on October 12, his administration has a number of ways to approach the October 15 deadline for certifying the nuclear deal. Thus far, rhetoric from the president and members of his cabinet have fueled speculation that he will withhold certification.

Rather than abandoning its considerable leverage over proponents of the deal, however, the administration should view the certification debate as an opportunity to press them on long-delayed steps they have indicated a willingness take on Iran. In doing so, the president should push for what he wants most while remaining mindful of what he can realistically obtain.

NO CONTEXT FOR DECERTIFICATION?

The administration has not yet created a context for decertifying the deal. Much of the relevant reporting and analysis tends to conflate decertification with two other actions: first, finding Iran in noncompliance with the JCPOA, and second, deciding to stop fulfilling U.S. obligations under the JCPOA. These misperceptions have led many to conclude that decertification is either unwarranted or immediately harmful to U.S. interests. If the administration is seriously considering decertification, it needs to make a much greater effort to counter those errors and create a context in which decertification can be judged on its own merits rather than being confused with other options.

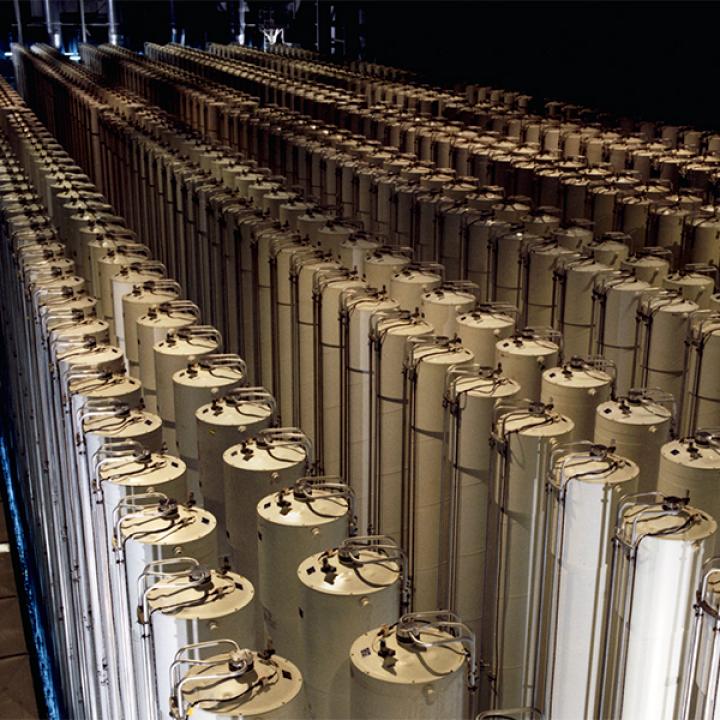

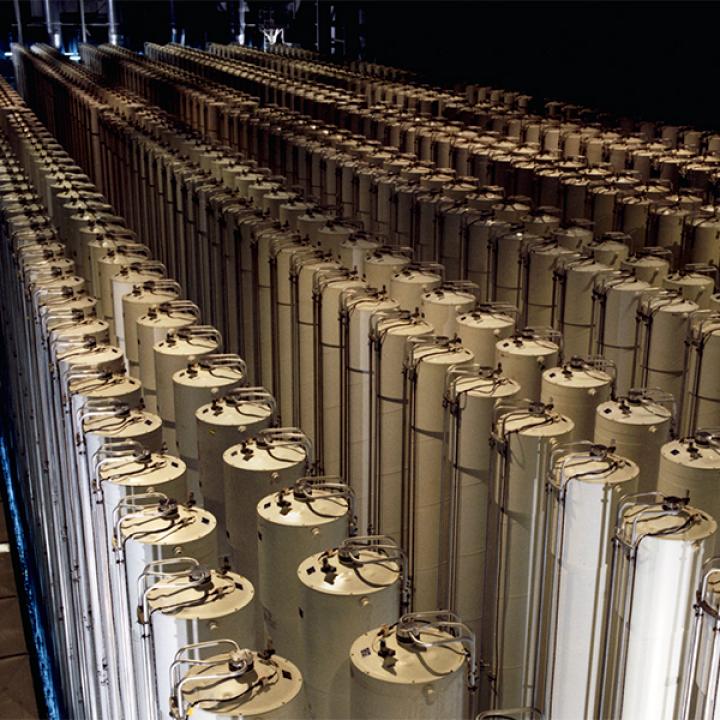

On the first point, the text of the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015 (INARA) is clear that certification does not depend on what the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) says about Iranian compliance. Rather, the INARA standard is a U.S. determination that "Iran is transparently, verifiably, and fully implementing the agreement, including all related technical or additional agreements," which is a much more demanding standard than the IAEA's. On August 22, for example, Iranian nuclear official Ali Akbar Salehi claimed that pictures of the supposedly disabled Arak reactor had been "Photoshopped," and that restarting the reactor would take only a few months. The IAEA has not reacted publicly to Salehi's comments; in fact, its procedures may not require it to comment on such statements. Yet failure to clarify such provocative Iranian statements makes it difficult for the Trump administration to say that the nuclear accord is being "transparently, verifiably, and fully implemented."

On the second point, a decision to decertify would not automatically change existing U.S. sanctions on Iran or end any of the waivers/suspensions Washington issued in order to implement the JCPOA. The president can decide at any time to reimpose pre-JCPOA sanctions, and if he withholds certification under INARA next week, that makes no difference to the waivers now in place. In other words, certifying under INARA and waiving JCPOA-related sanctions are independent events.

As a practical matter, a presidential decertification would almost certainly spur a congressional debate about whether to reimpose sanctions by law, and the White House is unlikely to act until that debate is over, especially since INARA provides expedited review within sixty days. During the congressional debate period, the administration would therefore have considerable leverage over supporters of the deal -- be they domestic, European, or Iranian -- to press for actions that increase the likelihood of the United States staying within the deal.

WHAT WASHINGTON CAN REALISTICALLY PRESS FOR

Under the JCPOA, the United States and its allies retained the ability to isolate Iran for behavior that falls outside the nuclear deal's scope. Indeed, the Obama administration repeatedly drew attention to Tehran's terror sponsorship, ballistic missile testing, weapons procurement, and human rights abuses by issuing new designations under remaining sanctions authorities. The Trump administration has continued that approach, and the certification decision need not alter it -- Washington could push European allies to do more on all these fronts if they want to see the United States recertify or at least stay within the JCPOA.

U.S. pressure has also highlighted Iran's use of deceptive financial practices to fund its illicit activities. Given the ongoing nature of such practices, Washington should urge European authorities to remind their banks about the importance of enforcing "know your customer" rules. Such prodding would be especially appropriate because the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and other Iranian entities remain subject to EU asset freezes.

The administration should also press for vigorous implementation of all relevant UN Security Council resolutions. In addition to reemphasizing Resolution 2231 -- which implemented the JCPOA and carried forward the remaining UN sanctions infrastructure against Iran -- Washington could remind the international community that Tehran is openly flouting the council's prohibition on Iranian arms exports and its separate bans on arms exports to Hezbollah and Yemen's Houthi rebels. For example, the administration could galvanize concerns about Hezbollah's role in stoking sectarian violence in Syria as a way to restart procedures on blocking Iranian arms transfers to the group, specifically by resuming some of the additional efforts implemented after the 2006 Hezbollah-Israel war. Along the same lines, Iran's largest airline, Mahan Air, has repeatedly transferred arms to the group's forces in Syria, yet Mahan planes are still permitted to fly freely across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Given Hezbollah's increasingly important military role in the region, U.S. officials should urge their European counterparts to both ban Mahan flights and take action under the EU's 2014 terrorist designation of Hezbollah's military wing.

Moreover, a number of Iranian missile development entities remain subject to UN and EU sanctions, and these lists could be augmented with minimal implications for Europe's growing commercial and diplomatic ties with Iran. On nuclear matters, Washington could encourage more vigorous international enforcement of the "procurement channel" that Iran is supposed to use to purchase nuclear-related technology, as well as start discussions on forging P5+1 consensus about what happens when the JCPOA's sunset dates arrive. Through it all, U.S. officials should bear in mind that sanctions are only one part of a policy that needs to involve other elements of national power, including diplomacy and appropriate military steps (e.g., intercepting arms transfers at sea).

The challenge for the Trump administration is to figure out the best means of reinvigorating and reinforcing international action on these issues. Any decision about whether to decertify the nuclear deal and reimpose sanctions should be made in this context: what will the United States get if it recertifies and/or continues waivers, and what will it lose if does not recertify? If the administration moves forward without asking allies to act in these areas, then it cannot expect these partners to cooperate in the future.

SHIFTING THE RHETORIC

Washington's options are much broader than the extremes of recertifying the JCPOA as is or leaving the deal altogether. Taking stronger action against Iran's destabilizing regional activities and expanding missile program while calling for full enforcement of the nuclear deal could give the president sufficient justification for either recertifying the deal later on or decertifying it while continuing to waive/suspend sanctions. Those who wish to see the United States stick with the JCPOA would be ill advised to refuse such middle courses out of hand. If critics insist that they will accept nothing less than Trump's capitulation, they will put the JCPOA at grave risk.

Katherine Bauer is the Blumenstein-Katz Family Fellow at The Washington Institute. Patrick Clawson is the Institute's Morningstar Senior Fellow and director of research.