- Policy Analysis

- Policy Alert

Pyongyang's Posturing: The Iranian Dimension

Just hours before Pyongyang claimed to have tested a hydrogen bomb, Iran unveiled another underground facility and showed off North Korean-designed long-range missiles.

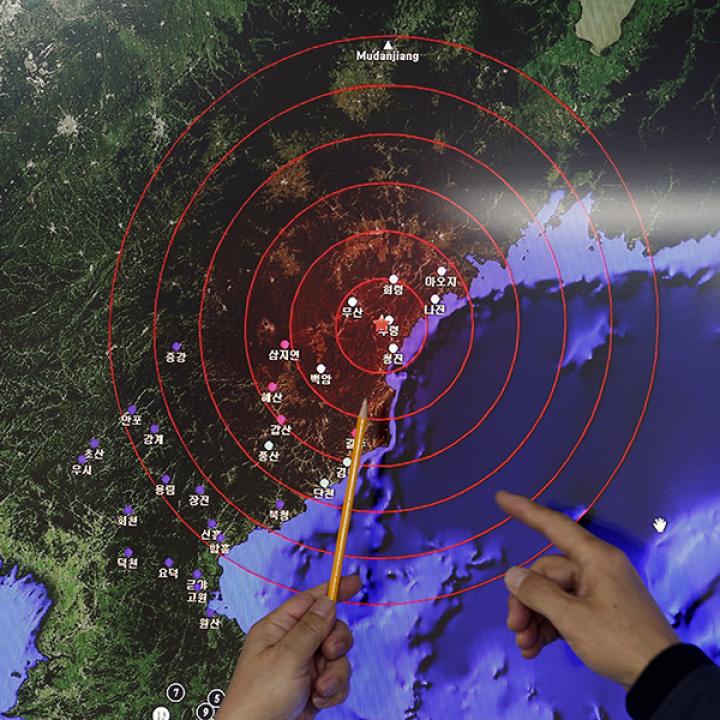

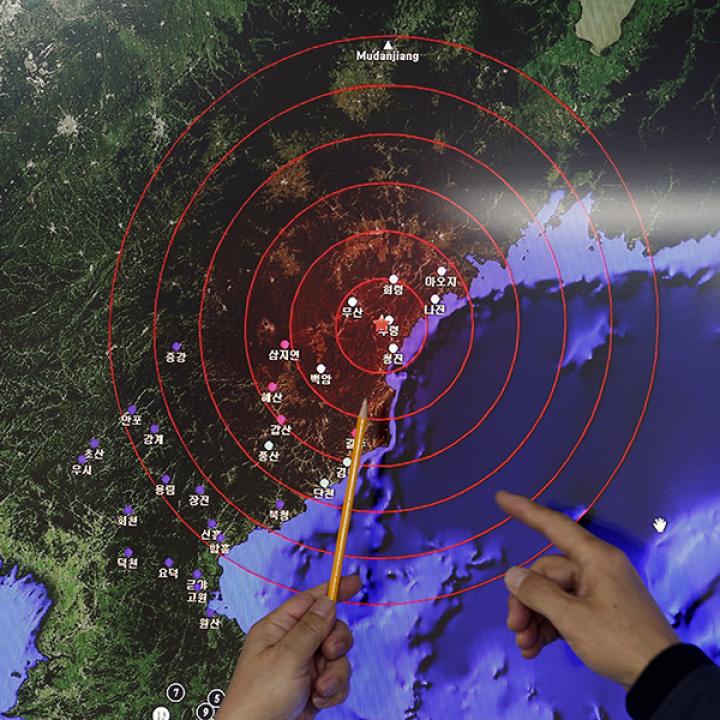

Evidence of North Korea's January 6 nuclear test is still being analyzed, but already there is doubt about whether it was a powerful hydrogen bomb, as Pyongyang has claimed. Rather, it was probably a fission-type atomic bomb similar to the design the country has already tested three times, although perhaps a more sophisticated version known as a boosted weapon. Whatever the case, the incident's immediate consequences relate to East Asia, where South Korea, Japan, and even close ally China were already concerned about Kim Jong-un's petulant leadership style. Yet there are several bothersome connections to the Middle East as well, which should prompt international attention.

North Korea's first nuclear tests in 2006 and 2009 are believed to have used plutonium extracted from spent reactor fuel. Its 2013 test may have used high-enriched uranium obtained from a centrifuge enrichment plant, the existence of which was revealed to an astonished visiting group of former U.S. officials and academics in 2010. Pyongyang had acquired the centrifuge technology from Pakistan, including the comparatively efficient P2 machines, which are a great improvement over the P1 machines that dominate Iran's inventory, also originally obtained from Pakistan. Tehran is developing its own IR-2m machines, which are similar to the P2; such work is permitted under last year's U.S.-brokered nuclear deal.

There are overlaps in missile technology as well. Both Pakistan and Iran manufacture and operate versions of the North Korean Nodong missile, which has a range of around 1,000 miles and is capable of carrying a nuclear warhead. In Pakistan the missile is known as the Ghauri and forms part of the country's strategic nuclear force. Iran calls its version the Shahab-3 and has developed a more advanced variant named Emad. On January 5, Iranian state television showed what it said were Emad missiles on launcher vehicles in a tunnel complex being inspected by parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani. The photos were similar to ones shown in October, purportedly from a different tunnel complex.

Despite the nuclear accord with the United States and longstanding international restrictions on its ballistic missile activities, Iran continues to develop missiles of various types. It was the recent testing of an Emad type that violated a UN Security Council resolution and was poised to trigger new U.S. sanctions on Iran last week, until a sudden decisionmaking U-turn in Washington. The United States is also concerned about sales of North Korean missile equipment to Iran, as well as the presence of Iranian technicians in North Korea, where they are working on a missile booster.

These developments, along with the latest flare-up in Tehran's relations with Saudi Arabia (see "Saudi-Iranian Diplomatic Crisis Threatens U.S. Policy"), add a dangerous dimension to ongoing Gulf tensions. While technical experts can muse about imperfections in North Korean nuclear weapon technology and the complexities of finding a missile/warhead combination that would actually work in practice, perception is its own reality. If Iran still has links to North Korean missile technology, it may be able to access nuclear weapon skills as well. Confusing as it may be for diplomats seeking to ease tensions in the Middle East, the relationship between Tehran and Pyongyang should not be considered a separate issue.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Gulf and Energy Policy Program at The Washington Institute, and coauthor (with Olli Heinonen) of Nuclear Iran: A Glossary.