- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 2941

Qatar Diplomacy: Unraveling a Complicated Crisis

President Trump's personal intervention to end the split between U.S. Gulf allies will be a major test of his authority—and his patience.

Since a diplomatic row erupted last June between Qatar and the coalition of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Bahrain, various efforts to resolve the dispute have failed. In the past week, however, Washington appears to have launched a new round of U.S. diplomacy.

First, the White House reportedly intends to invite all six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) to a May summit at Camp David. And on February 27-28, President Trump held separate telephone calls with Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Muhammad bin Zayed of Abu Dhabi (the leading emirate of the UAE), and Emir Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani of Qatar. The White House readouts of the three conversations were essentially identical—each leader was thanked for highlighting ways in which all GCC states "can better counter Iranian destabilizing activities and defeat terrorists and extremists."

President Trump then spoke with Egyptian president Abdul Fattah al-Sisi on March 4. This time the readout mentioned "Russia and Iran's irresponsible support for the Assad regime's brutal attacks against innocent civilians," as well as a pledge to "work together on...achieving Arab unity and security in the region." So far there has been no report of Trump contacting the fourth leader of the Arab coalition, King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa of Bahrain.

What is the context?

Saudi Arabia is the region's largest oil exporter; the UAE is second. Qatar is the world's largest exporter of liquefied natural gas and shares its largest gas field with Iran. By virtue of its small citizen population of around 300,000, Qatar also has the world's highest per capita income, and it has used this wealth to carve out an independent foreign policy, for example inviting Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to the 2007 GCC summit in Doha. At the same time, Qatar hosts 10,000 U.S. military personnel at al-Udeid Air Base, from which U.S. aircraft routinely launch strikes on Islamic State targets in Syria.

Who are the key players?

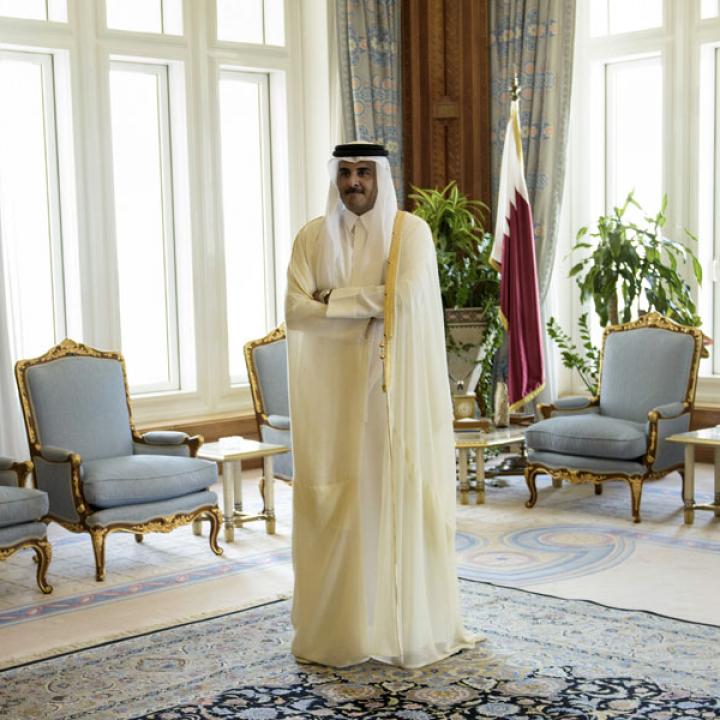

The two most important figures in resolving the dispute are the crown princes of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi, respectively known as MbS and MbZ, and the de facto leaders of their countries. MbZ has apparently taken the lead role on this matter. On the Qatari side, Emir Tamim is not as powerful on the regional stage, and his father, Hamad bin Khalifa, is not regarded as a significant player by foreign diplomats in Doha, despite Emirati claims that he is crucial. U.S. diplomacy is led by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary James Mattis. Emir Sabah al-Ahmed al-Sabah of Kuwait has also been laboring for months to resolve the crisis.

What is the dispute?

Unraveling the most relevant differences between the Arab coalition and Qatar has become increasingly complicated. Their historical enmity predates the discovery of local oil and gas deposits. The current crisis also seems like a re-run of a previous row in early 2014, when Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from Qatar for several months after accusing it of meddling in their domestic affairs. When the latest rupture occurred, the Arab coalition produced a list of thirteen demands (subsequently recast as six "principles") and closed Qatar's land border and air links.

At times, the key issue—particularly for MbZ, but also for Egypt—seems to be Doha's reputation for allowing exiled Muslim Brotherhood members to live in Qatar. Other demands relate to restraining Al Jazeera's often-inflammatory satellite television broadcasts and ceasing support for terrorism. But the first item on the coalition's list is all about Iran. Specifically, Doha has been ordered to do the following: "Curb diplomatic ties with Iran and close its diplomatic missions there. Expel members of Iran's Revolutionary Guard from Qatar and cut off any joint military cooperation with Iran. Only trade and commerce with Iran that complies with U.S. and international sanctions will be permitted."

How deep are the differences?

MbS commented this week that the crisis with Qatar "could last for a long time," comparing it with the U.S. embargo on Cuba. Yet however serious the dispute may be to the parties themselves, some of their behavior thus far seems petty to outsiders. For example, the children's section of the new Louvre Abu Dhabi museum recently displayed a map of the southern Gulf that erased the Qatari peninsula. The museum described the omission as an "oversight," but the problem resurfaced just last week, when a map provided to Bloomberg television by the Saudi state-owned oil company made an identical omission. (Bloomberg offered an on-air apology a day later.) Meanwhile, MbZ has been hosting peripheral disenchanted members of the Qatari royal family in Abu Dhabi; one left in January after protesting he was being held against his will; another was welcomed on February 20.

How do reports of foreign hacking fit in?

Both Qatar and the UAE have used cyberwarfare during the dispute. At some point, the personal email account of the UAE ambassador to Washington, Yousef Al Otaiba, was compromised by individuals presumably acting on Doha's behalf. And last May, just after President Trump celebrated Gulf unity at a summit in Riyadh, hackers infiltrated the Qatar News Agency and sent out a story that was supportive of Iran, prompting outrage from the UAE and Saudi Arabia. U.S. officials have reportedly concluded that the hack was perpetrated by or on behalf of the UAE.

Are there policy differences within the Trump administration?

President Trump's initial tweets about the dispute appeared to take Saudi Arabia and the UAE's side, while Tillerson and Mattis seemed to regard the crisis as a distraction from Washington's main regional priority: supporting Gulf allies against the Iranian threat. But they now seem to share unity of purpose.

In January, Tillerson and Mattis jointly hosted the first U.S.-Qatar Strategic Dialogue, which was reportedly a great success. And when MbS visits the White House this month, Qatar will be on the agenda. President Trump may try to split him off from MbZ on this issue; MbZ himself has been invited for a White House meeting a few days later, while Emir Tamim is scheduled to visit in April. Whether President Trump can broker an accord may depend on the extent to which the three leaders pride their relationship with him and the United States. The proposed Camp David summit in May is unlikely to happen unless the crisis is resolved by then.

Is the crisis amenable to negotiation?

The coalition's demand that Qatar break diplomatic links with Iran is especially thorny given Tehran's complicated relations with several of the parties. Although Saudi Arabia and Bahrain broke off formal relations with the Islamic Republic after the Saudi embassy in Tehran was attacked by rioters in 2016, the UAE has maintained official links. Iran has a large consulate in Dubai, where a significant proportion of UAE citizens with Iranian heritage live. Iran is also the UAE's second-largest export market, accounting for around 9 percent of its outgoing trade, worth about $30 billion annually.

Meanwhile, Qatar's ties with Iran have been exaggerated at times. The coalition demand to expel Revolutionary Guard troops is probably based on a false news report that such personnel had been stationed outside palaces in Doha. Foreign diplomats posted in the Qatari capital say that there is no truth to the allegation, and that there are no significant military or political ties between the two countries. Their bilateral trade has increased only marginally in the past few months and remains very low. Now that its border with Saudi Arabia is closed, Qatar has to import everything it needs via sea or air. Iranian milk is on sale in Qatari supermarkets, but so is milk from Turkey and Britain.

Is there an Israeli angle?

Israel has a stake in the dispute given its own concerns about Iran and terrorism, but its relationship with the Gulf players is similarly complicated. In late January, after prominent American Jews visited Doha at Qatar's expense, the Israeli embassy in Washington tweeted, "We oppose Qatar's outreach to pro-Israel Jews." At the same time, Israel used to have a diplomatic office in Doha, and its passport holders are still permitted entry to attend conferences in Qatar. Israel is also grateful for Qatar's financial support to reconstruction efforts in Gaza and parallel mediation role with Hamas. Yet while such funds are required to pass through official Israeli channels, concerns persist that some of the money has been leaked to Hamas and similar groups for terrorist activity.

On the other side of the dispute, the UAE is central to what Israeli diplomats call the "iceberg strategy," which entails cementing discreet ties with Gulf states threatened by Iran. The UAE is the only Gulf state with an official Israeli diplomatic presence, in the form of a representative office to the International Renewable Energy Agency headquartered in Abu Dhabi.

Is there a domestic U.S. angle?

The New York Times reported last weekend that Special Counsel Robert Mueller was investigating Lebanese American businessman George Nader regarding possible UAE attempts to buy political influence via financial support for Trump's presidential campaign. Nader apparently received a detailed report from top Trump fundraiser Elliott Broidy about an Oval Office meeting in which Broidy lobbied the president to meet privately with MbZ, back the UAE's regional policies, and fire Secretary Tillerson. Broidy has accused Qatar of hacking his emails to get that report.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Gulf and Energy Policy Program at The Washington Institute.