- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

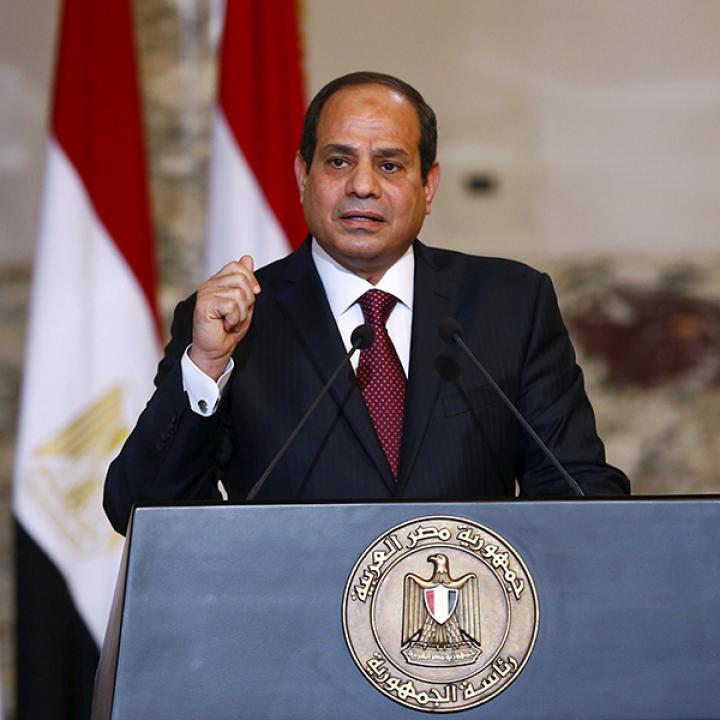

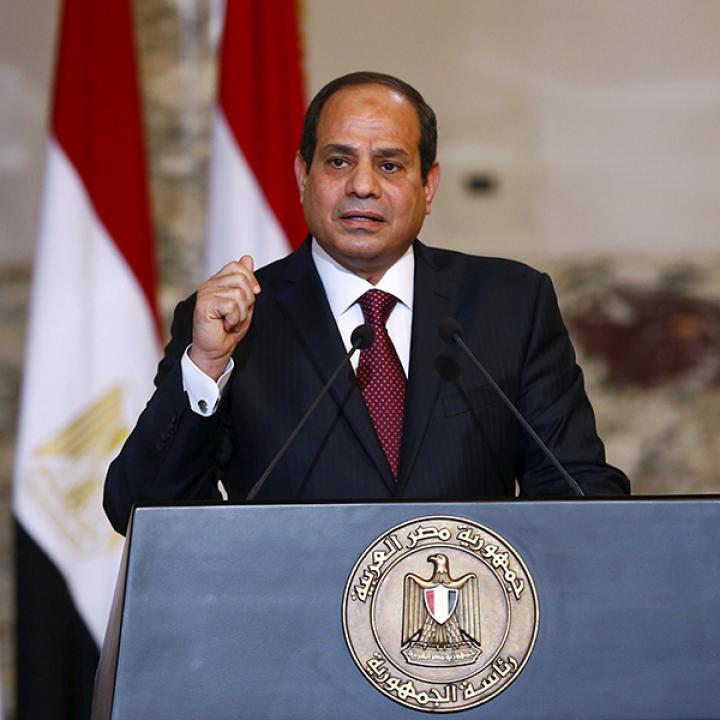

Sisi's New Approach to Egypt-Israel Relations

Cairo believes that relations with Israel are strategically and diplomatically beneficial, and the trend toward greater rapprochement will likely continue.

Since the Egyptian military’s entrance into political life and its toppling of former president Mohamed Morsi on July 3, 2013, there have been questions as to how Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s government will deal with Israel. Many wondered if the government would continue the current trajectory of relations, as relations underwent a chill during the Military Council and Morsi years, in part triggered by the storming of the Israeli Embassy in Egypt during September 2011. Until recently, relations between Israel and Egypt relied on Washington as mediator in negotiations. However, Sisi’s government has significantly altered this dynamic.

The escalation of the political crisis between Egypt’s secular opposition and the Muslim Brotherhood had largely overshadowed Egypt-Israel relations during the Morsi era. However, the Morsi government still made several steps towards freezing the Egypt-Israel relationship: it sent Prime Minister Hesham Qandil to the Gaza Strip during Israel’s operation “Pillar of Defense” in November 2012 and attempted a rapprochement with Iran.

Shortly after the July 3 military intervention, Israel began unequivocally backing the new regime. Israel launched diplomatic missions in Washington and several major European capitals to support Egypt’s new political situation and prevent a diplomatic blockade on Cairo. Nor were these efforts unrewarded; Egypt-Israel relations have witnessed unprecedented growth during the Sisi regime, often driven by Sisi himself.

When Sisi became the country’s de facto leader, his first challenge was the series of terrorist attacks against the military in the Sinai peninsula. Egypt’s security partnership with Israel immediately came into play; Sisi’s government coordinated with Israel, which gave Egyptian forces the green light to deploy in northern Sinai’s B and C Zones to fight armed Takfiri groups with heavy weapons, armored vehicles, and air incursions.

These actions went directly against what is stipulated in the security appendix of the Camp David Accords, and they demonstrated the flexibility and coordination between Egypt and Israel early in Sisi’s tenure. Confronting armed groups in the Sinai has remained one of the most important security issues shared by both countries. Israel itself has conducted a number of aerial intelligence missions to uncover terrorists’ hiding spots. However, in an attempt to avoid controversy Cairo has not made public the nature of its military-security partnership with Tel Aviv.

Sisi has also long been interested in personally involving himself with the peace process. In his first presidential address in 2014, Sisi stated: “We will work to achieve the independence of Palestine with its capital in East Jerusalem.” With this, Sisi seemed to stake his position on the contentious issue of East Jerusalem, dating back to former president Anwar Sadat’s opposition both of Israel’s annexation of the East Jerusalem territory and the claim of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. While Sisi’s support for East Jerusalem is the capital of Palestine caused some diplomatic fallout with Israel, his insistence on a two-state solution also weakened the position his supporters were attempting to build against Islamist groups, Nasserists, leftists, and the Salafist Nour Party – all of whom catered to popular opinion by refusing to recognize the State of Israel and claiming all Palestinian lands as solely Arab.

With Sisi’s emergence as the uncontested leader, none of his supporting political factions have been able to pressure him to change his relatively positive rhetoric about Israel. Sisi has instead turned the former narrative on its head, insisting that Egypt-Israel relations are a necessity in light of their shared regional foe: Hamas, seen as an extension of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. Thus, Sisi has shifted Egypt’s role with Israel from that of an “existential struggle” to a partnership of necessity.

During Israel’s “Operation Projective Edge” in Gaza, Sisi gained the perfect opportunity to adopt the image of peace mediator in the international community. Sisi benefitted from Israel’s refusal of international mediation for a ceasefire, which led Israel to resort to calling on Cairo to host negotiations with Palestinian factions and sign the ceasefire agreement. The image of Sisi as peacemaker helped in some part distract the international community from the government’s own challenges with domestic unrest.

Sisi’s movement towards public rapprochement with Israel is partially motivated by these experiences with massive domestic crises. Issues from economic stagnation to Egypt’s potentially decreasing share in Nile waters have pushed Sisi to reassert his regional leadership role. He has found an opening by presenting himself as a negotiator in one of the most sensitive international issues: the Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations. This position bolsters his domestic image as a strongman.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has responded favorably to Egypt’s shifting role as negotiator in the larger peace process, as it presents an alternative to the recent French Initiative. Moreover, further Egyptian involvement could reduce international pressure on Israel over its lack of serious steps towards negotiating with the Palestinians. Indeed, Sisi’s initiative does not cost Netanyahu anything other than more negotiations. Egypt has no clear conditions for negotiations, such as restricting settlement expansion in the West Bank.

Relations have also strengthened through diplomatic developments. Egyptian Ambassador Hazem Khairat participated in the sixteenth Herzliya Conference in Israel, titled: “Shared Israeli Hope: Vision or Dream?” Khairat represented Egypt’s first official participation in the conference, which centers on Israel’s security and defense policies. During the conference, the Egyptian ambassador stated that Israel and the Palestinians must commit to reaching peace and that the two-state solution is the only solution, and emphasized that ignoring this truth may cause an explosion that all parties are trying to avoid.

Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry’s recent visit to Israel was also monumental as the first of its kind since 2007. His meeting with Netanyahu in the Israeli Prime Minister’s office headquarters in Jerusalem rather than Tel Aviv was incredibly symbolic, as it sidestepped the traditional diplomatic taboos of Jerusalem to which all Egyptian presidents had abided since Mubarak and the transitional president Adly Mansour.

After years of Egyptian-Israeli relations limited to security and intelligence coordination, Egyptian diplomacy now aspires to a pivotal role in the relationship. Shoukry’s picture next to the bust of Theodore Herzl—considered to be one of the ‘fathers of Zionism’—appeared to send the message that he had reconciled the contradiction between Herzl’s Zionism and the land’s historical Arab foundations. And the intimacy depicted by Shoukry and Netanyahu’s viewing of the European Championship reflects the Egyptian government’s lack of concern over local reactions to the growth of Egyptian-Israeli relations. Correspondingly, Netanyahu is also portraying the visit as a personal political accomplishment, where he has strengthened Israel’s relations with its largest historical enemy. The visit demonstrated a recent trend where Israel has been able to shift its relationships with Arab countries from behind closed doors into the public sphere.

Although Sisi has always demonstrated an interest in Egyptian-Israeli relations, several regional shifts have increased the urgency of this diplomatic rapprochement. The timing of Shoukry’s visit to Jerusalem corresponded with the agreement to normalize Turkish-Israeli relations, which had deteriorated considerably after the storming of the Turkish “Mavi Marmara” flotilla that attempted to break the Gaza blockade. Turkey and Israel recently reached an agreement under which aid can be delivered to Gaza and the Turkish Housing Foundation can complete its projects there. With Turkish-Israeli reconciliation threatening Egypt’s role as peacemaker, the country is now exerting great effort to get confirmation from Israelis that it can continue to play a pivotal role in the Palestine issue, particularly with regards to the Sinai-bordering Gaza Strip.

Netanyahu’s visit to the Nile Basin countries also provoked outrage in Egypt as a consequence of both Egypt’s declining—and Israel’s ascending—role in Africa. In this way, Shoukry’s presence in Jerusalem acted as a way to reassure the Egyptian public that Israel’s presence in the Nile Basin is that of an ally and not an enemy. Similarly, the visit raised Cairo’s hopes of Israel functioning as a mediator between it and as Ethiopia prepares to launch the Grand Renaissance Dam project, which Egyptians fear will stop the country’s access to 11 to 19 billion square meters of fresh water.

Essentially, Cairo believes that relations with Israel are strategically and diplomatically beneficial for the Sisi government and the country’s regional standing. This trend toward greater rapprochement is likely to continue; there are even hints that Egypt will extend an invitation to Netanyahu to come to Cairo for a historic visit, much like that of Sadat to Jerusalem in 1977.