- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 2614

The Battle for Deir al-Zour: A U.S.-Russian Bridge Against the Islamic State?

The survival of the regime enclave in Deir al-Zour is fundamental to the anti-IS fight, so Washington and Moscow's allies on the ground may need to race to its rescue sooner rather than later.

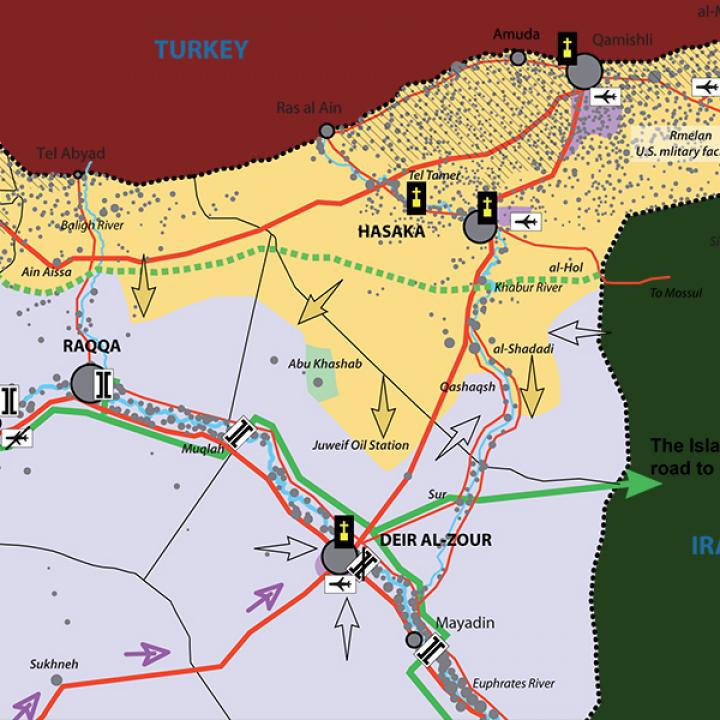

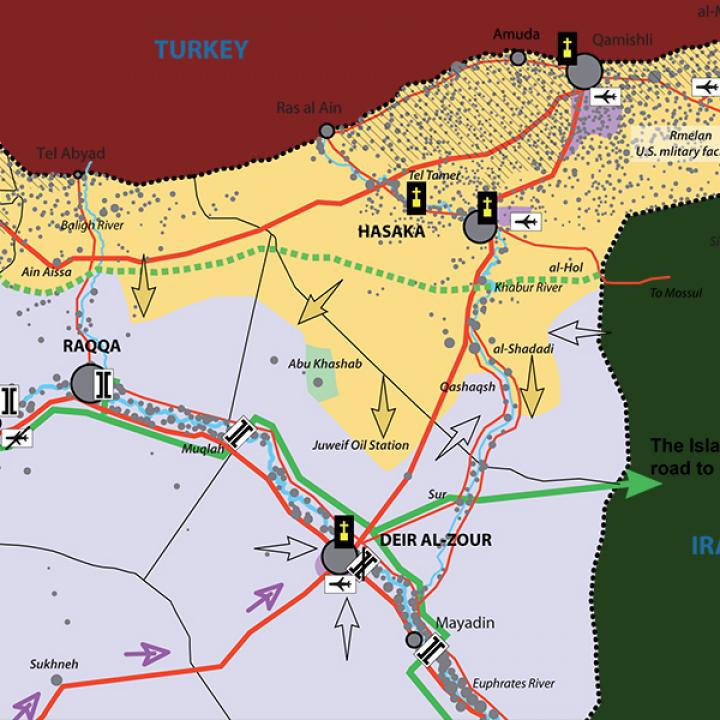

In recent weeks, the situation has become increasingly critical for the thousands of Syrian civilians and army personnel surrounded in Deir al-Zour. Since the city was first isolated early in the war, the only means of resupplying it has been by air, and Islamic State (IS) forces are now escalating their pressure to take it before the Assad regime can reopen the road from Palmyra. The latter scenario would trap local IS forces between the army to the south and advancing Kurdish forces from the north, threatening to sever communications between the IS enclaves in Syria and Iraq. This opens an avenue of potential cooperation -- or, at least, rapid pursuit of shared interests -- between the United States and Russia, the respective patrons of the Kurds and the regime.

COMPARABLE TO ALEPPO

Deir al-Zour has suffered the same fate as Aleppo since summer 2012. First, rebels entered the city and captured several neighborhoods. Over time, the army abandoned the rest of the province and regrouped on the southwestern bank of the Euphrates River, between the city, the airport, and the road to Palmyra. The regime was no longer able to hold a province whose strong tribal presence had made residents rebellious to authority well before the war. Even the army's attempts to retake fallen neighborhoods inside the city failed repeatedly, despite the October 2013 deployment of elite Republican Guard regiments and one of the regime's best officers, Gen. Issam Zahreddine.

CLICK ON MAP TO VIEW HIGH-RESOLUTION VERSION

The task of defending Deir al-Zour became more complicated after July 2014 because IS had eliminated other groups across the province by then. When IS elements took Palmyra in May 2015, regime forces were plunged into the greatest distress. Although the regime eventually liberated Palmyra this past March, the pressure on Deir al-Zour has only grown. Efforts to shore up the city's airport have become particularly crucial for survival, with defenders fearful of suffering the same fate as the troops massacred by IS at Tabqa military base in November 2013.

The army remains on the defensive in Deir al-Zour because its available forces are limited. Moreover, General Zahreddine prefers to draw IS out into the desert because his tanks are more effective there than in urban fighting. Consequently, the front lines in Deir al-Zour city have hardly moved at all since summer 2012.

As for IS, it has focused on attacking support points with suicide bombers, forcing soldiers to flee and then chasing them down. On several occasions, such tactics have helped IS fighters enter the perimeter controlled by the army. In January 2016, the group invaded the northern neighborhood of Baghiliya, killing 280 people (soldiers and civilians) and capturing 400 prisoners before the army and the National Defense Forces (NDF) drove them out. Indeed, irregular NDF units play a crucial role in the city's defense because the local Republican Guard contingent is limited to 2,000 soldiers at present. The militancy and loyalty of these irregulars is strong due to the fate that awaits them and their families if the whole city falls to IS. The group's deadly raids have already included massacres of civilians, (e.g., 700 Sheitat tribespeople were slaughtered in August 2014), leaving no alternative but to fight until the army reopens the Palmyra road.

A STRATEGIC CHOKEPOINT FOR THE ISLAMIC STATE

Retaking Palmyra was a relatively simple step in the wider, more complicated offensive to break the siege around Deir al-Zour. Led by the capable regime officer Gen. Suhail al-Hassan, efforts to open up the road from Palmyra have been slow. The resumption of fighting in northeastern Latakia and Aleppo forced the army to withdraw some of the troops intended for the Deir al-Zour campaign, and while General Hassan could still reach the city with limited forces, he cannot secure a 300-kilometer corridor without reinforcements. Moreover, IS elements remain powerfully implanted in the Jabal Abu Rujmayn area between Palmyra, Salamiya, and Ithriya, threatening two crucial roads. They also pose a constant threat to Palmyra itself, so the regime will likely need to eradicate them before it can safely advance toward Deir al-Zour.

CLICK ON MAP TO VIEW HIGH-RESOLUTION VERSION

Yet the besieged city may not have the luxury of patience. After a year of repeated IS assaults, its 100,000 inhabitants are only surviving thanks to air-dropped food supplies -- cargo planes can no longer land at the military airport due to heavy fire from nearby enemy forces. The army is fortunate that IS lacks surface-to-air missiles or heavy artillery, but the prospects are grim even without these weapons in play.

The Islamic State increased its efforts against Deir al-Zour in recent months due to the various setbacks it suffered against regime forces to the west (at Palmyra and Kuwaires airport) and against the Kurds to the north. Since summer 2015, the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Arab allies in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) have made significant progress southward. They chased IS from Hasaka city in July, then advanced down the Khabur Valley toward al-Shadadi in February, taking positions around Juweif oil station just thirty-five kilometers from Deir al-Zour. In the PYD's case, the southward push could be the price the Kurds are paying for American support in Manbij, the next step in their goal of uniting their separate cantons along Syria's border with Turkey.

Meanwhile in Iraq, forces linked to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) have driven IS out of Mount Sinjar, while Peshmerga forces from the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) took over Sinjar city in November 2015. As a result, supply lines and communications between the IS "capitals" of Mosul and Raqqa could be cut off by SDF units from Hasaka and Syrian army units from Palmyra, making the Deir al-Zour enclave a priority target.

From a tactical perspective, breaking the siege and launching a counteroffensive against IS will be tricky. The two local bridges over the Euphrates have been destroyed -- one by IS in May 2013, the second (only a few hundred meters away) by regime forces in September 2014. Although the latter move was intended to impede IS fighters from crossing the river, it will also keep the army from quickly regaining a foothold on the other side in the event of an offensive. The nearest bridges are located 70 kilometers to the northwest (at Muqlah) and 50 kilometers to the southeast (at Mayadin). Alternatively, the army could install a temporary bridge inside the city or use amphibious vehicles to reach the other bank, which seems difficult. Therefore, the PYD and its Arab allies may be in a better position to cut the Islamic State's route between Mosul and Raqqa. Yet the army can greatly assist that effort by retaking the road from Palmyra, which would prevent IS forces from opening alternative routes on the southern side of the Euphrates.

U.S.-RUSSIAN COOPERATION ON DEIR AL-ZOUR?

Given all of the above factors, the survival of the regime enclave in Deir al-Zour is fundamental to the fight against the Islamic State. If the Syrian army and PYD-SDF forces are able to create a junction there, they would effectively encircle all IS forces in Syria and pave the way for a campaign against Raqqa. If one assumes that the United States and Russia are both interested in the complete destruction of IS in Syria, they could greatly facilitate that goal by further prodding their local allies toward Deir al-Zour. This means increased U.S. air support for Kurdish forces advancing south, and robust Russian air support for Syrian army forces advancing from Palmyra. In that scenario, Deir al-Zour could become the Middle Eastern Torgau, the riverside German city where the U.S. Army met the Red Army at the end of World War II while defeating a mutual enemy.

Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.