- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 2726

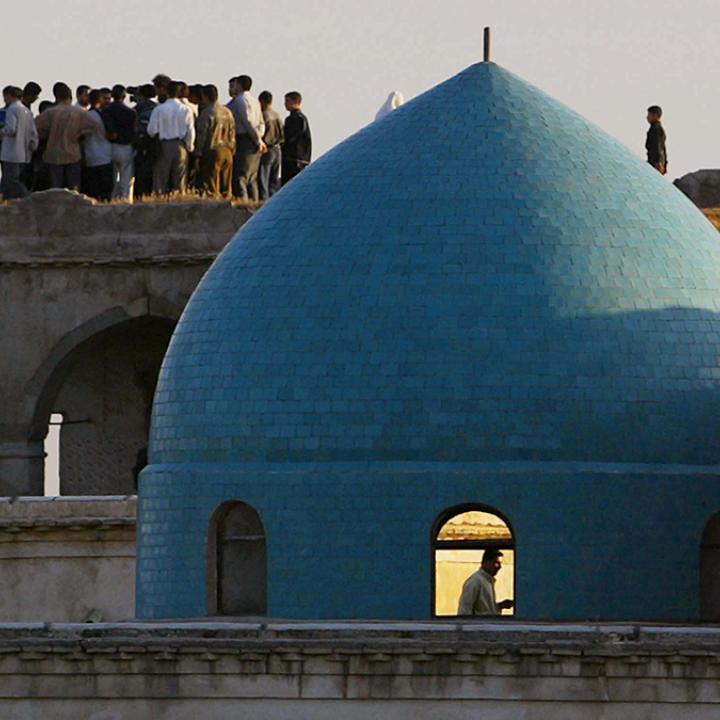

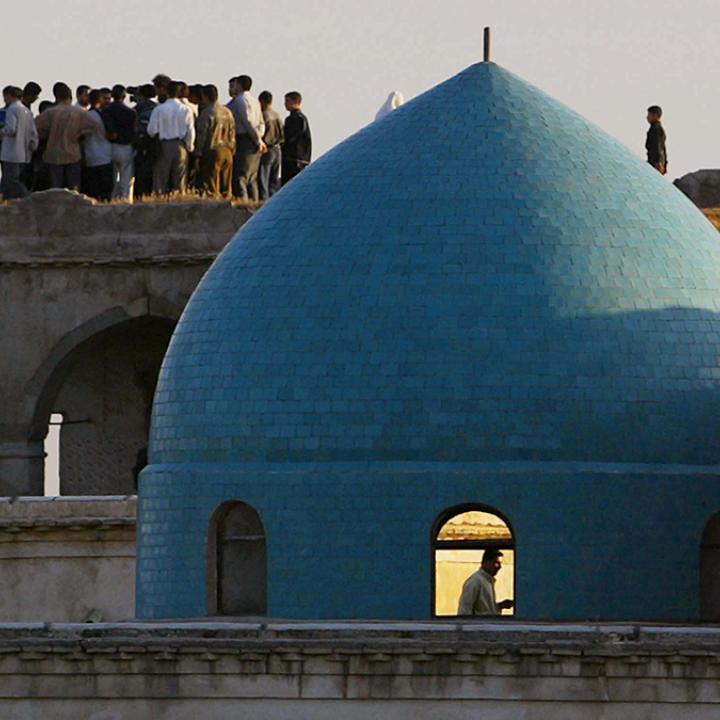

The Day After Mosul: Lessons from Kirkuk

Read or watch a conversation between a Washington Institute expert and the governor of Kirkuk, who shares firsthand perspectives on how Iraqi authorities and their partners can handle ethnic tensions in post-liberation Mosul.

On November 14, Michael Knights and Najmaldin Karim addressed a Policy Forum at The Washington Institute. Knights, a Lafer Fellow with the Institute, relayed impressions from his recent two-week visit to Iraq, where he spoke with military leaders serving on the frontlines. Karim was elected governor of Kirkuk province in 2011 after years of service as a pioneering Kurdish activist, Peshmerga medic, and opposition leader during the Saddam Hussein era. The following is a rapporteur's summary of their remarks.

MICHAEL KNIGHTS

As the battle rages on in Mosul and Ninawa province, most experts are focusing on what comes next for this multiethnic, cross-sectarian region. The sheer scale of the battle makes it unique; it consists of seven division-size units converging on a massive city, and the troops involved represent every ethnicity and religious sect found in Iraq. Although the battle is unfolding in a conventional manner, it is marked by uneasy coexistence between Shiite militias, Turks, other foreign troops, journalists, and so forth.

The battle is shaping the country's future political environment in several ways. First, it is engendering increased Sunni acceptance of the Iraqi security forces and the central government, even in traditionally less friendly areas like eastern Mosul. Second, the unprecedented cooperation between the Peshmerga and Iraqi government forces could translate into greater mutual trust between leaders of the two factions. This cooperation fits into a larger dynamic of positive interaction between Baghdad and Erbil on a number of issues, including Kurdish sovereignty and a shared economic space.

Looking to the future, the success of post-battle stabilization efforts remains a question. Challenges include managing volatility, establishing justice, policing the area, and resettling internally displaced persons (IDPs). At a macro level, Iraqis also face the hurdles of reconciliation, decentralization, and demobilization.

At the moment, there are two competing ideas regarding stabilization. The first is to move people along sectarian lines into areas where they feel safe. The second is to bring better representative government to the people where they already are. It remains to be seen which vision will become reality.

U.S. policy toward Iraq is not highly scripted, but Washington's lack of a detailed plan is not necessarily a bad thing. The United States should focus on broad objectives moving forward, all the while playing the role of honest broker. And if Washington wants to fight extremism, it will need to remain in Iraq long enough to finish the job on not only the Islamic State (IS), but also the broader stabilization effort, since only long-term stabilization can break the cycle of intervention. Working under the aegis of the Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve also helps cement the international alliance against extremism; it is a form of large-scale burden-sharing that can protect U.S. interests and, perhaps, extend beyond defeating IS.

NAJMALDIN KARIM

The most recent IS attack on Kirkuk demonstrates both the challenges the province faces and the advantages it holds. IS fighters mix easily among the population of local residents and IDPs, especially given that many of them are teenagers. Yet Kirkuk remains resilient. Rather than running away, locals -- including Sunni Arabs -- cooperated with the security forces to capture those who perpetrated the latest attack. Iraqi forces quickly took back all areas that were seized, and IS did not manage to gain control of any government buildings.

Still, the underlying problems that allow extremism to take root have not been resolved; there is still a Shiite-Sunni divide, as well as differences between Kurds and the central government. Moreover, extremism will likely outlive IS. The district of Hawija, for instance, has always been a hotbed of terrorism. Once IS leaves for good, terrorist groups will continue to operate like they did before the organization's arrival. Although the nascent cooperation between the Peshmerga and the Iraqi security forces is a positive development, it remains shallow for now, with both factions seeking sole credit for successes.

Another looming challenge is resource distribution, which has become more of a problem with the surge of Sunni Arab IDPs into the city. Kirkuk residents continue to share their schools, electricity, medicine, and water with these IDPs while receiving very little assistance from Baghdad. Due to sectarian strife, these displaced persons are often unable to return to regions in Diyala and Salah al-Din provinces that have supposedly been liberated from IS. If people cannot return to their homes in safe areas, Iraqis will never manage to build the country they hope to see in the future.

A final barrier to reconciliation is the existence of professional politicians who capitalize on the divides between ethnic and sectarian groups. The reality on the ground is much different, as members of these groups interact and coexist quite peacefully. The government must listen to the needs of the people and look beyond these professional politicians in order to rebuild the country.

Iraqis also expect that the incoming U.S. administration will stand by those who fight IS -- and no one has done that better than the Kurds. Perhaps Donald Trump, a man who is new to politics, will bring fresh ideas to the table regarding U.S. policy in the Middle East.

As for Mosul, the battle will require a long-term investment. Various competing factions -- including the Nujaifi camp, the central government, the Shiite militias, and Sunni Arabs -- have different visions for the city's future. One proposal is the creation of locally administered regions based on sect and ethnicity, an idea that appeals to many minorities, including Christians and Yazidis. Whether or not decentralization is a feasible solution, the lesson from Kirkuk is that the government must distribute resources equitably among all groups in order to build trust and spur reconciliation.

This summary was prepared by Kendall Bianchi.