- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Thomas Parker’s Comment on Maged Atef’s “Revelatory Elections – A State of Divide and Rule”

I want to thank Mr. Maged Atef for his fine article on the upcoming Egyptian election. I read it several times with great pleasure and interest since Egypt is one of the most important countries in the world, and not just in the Arab world.

My comments here go beyond the scope Atef’s analysis, looking forward to U.S. policy choices and toward Egypt’s own longer-term political future.

What Should United States Policy Be Towards the Election?

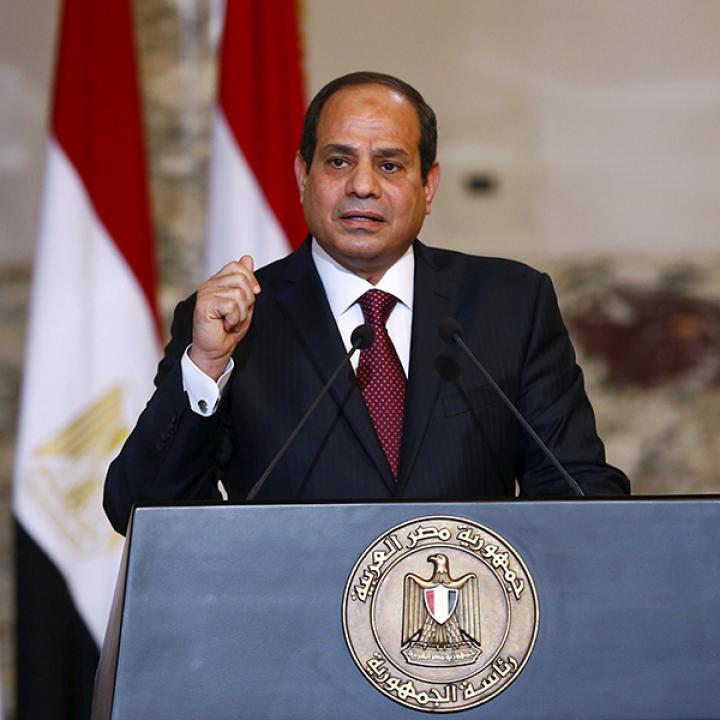

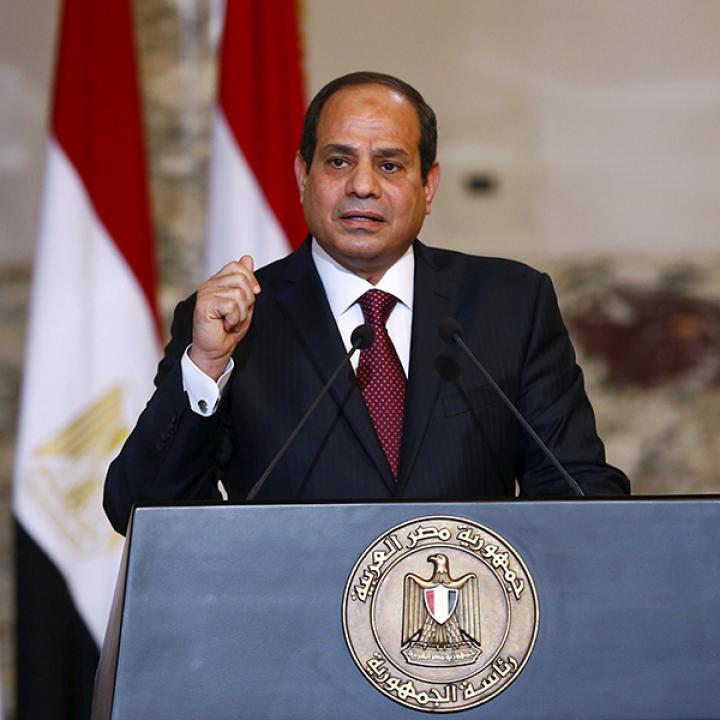

The optimal U.S. approach towards these kinds of less than democratic elections, orchestrated by friendly governments such as Egypt’s, always poses policy dilemmas. First, the U.S. does not want to undermine its relations with a political leader like President Sisi who will remain in power. So there is a tendency to ask why should we criticize an electoral process whose outcome is certain?

Second, the U.S. may have other priorities other than domestic governance. Most urgently right now, the U.S. needs Egypt’s cooperation on North Korea since Cairo has purchased North Korean weapons and allowed North Korean diplomats to use their embassy in Egypt as a base for military sales across the region. Given that North Korean is approaching the capability of destroying North American cities, isolating North Korea is a major U.S. interest.

Third, some in the U.S. are privately ambivalent about genuine democratic elections in the Arab world under present circumstances. Might not free elections result in the election of authoritarian religious parties unfriendly to the U.S. and more repressive than the regimes they replace? This took place in Egypt with the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013 and Hamas in 2007 in the Gaza Strip. One might argue that these autocratic religious regimes might not be re-elected, but of course, they rarely allow the political opposition to have a fair chance of regaining power through the ballot box.

What Can the U.S. Do?

Despite these considerations, the U.S. can and usually do use private diplomacy to urge friendly regimes to avoid excessively brutal tactics during these stage-managed elections. For example, the U.S. and European governments are almost certainly urging Egyptian authorities to avoid physically roughing up candidates. There is no excuse for the brutal attack against counselor Hisham Genena, former head of the Egyptian Central Auditing Organization and Lt. General Anan's deputy, which sent him to the intensive care unit, as recounted by Mr. Atef.

The Army Should Keep a Lower Profile

Mr. Atef usefully points out another developing danger to political stability. According to him, the Egyptian Army has become increasingly dominant in the Egyptian economy and it is no longer content with its role as a hidden political partner. Instead, President Sisi’s partnership with the army is out in plain view for the entire country to see.

This may solidify the president’s hold on power over the short term but it could jeopardize future political stability. Frustration with socio-economic conditions could easily begin to target the army itself. The lower the profile, the less the controversy, the greater the staying power.

Why President’s Sisi’s Next Term Should Be His Last

There is another potential danger for political stability in Egypt. Pro-government parliamentarians and media figures have been calling for the constitution to be amended to allow a president to have more than two four-year terms.

President Sisi said on CNBC television in November 2017 that he does not favor this: "I am for preserving two four-year terms and not changing it…We will not interfere with it." However, he later appeared to give himself some leeway in the interview, suggesting he might remain in power if it were in accordance with "the people's will." This hints at an orchestrated campaign whereby the president agrees to the “peoples’ call” to stay in office for an eventual third term.

Egypt, including its ruling elite, has a strong interest in ensuring that President Sisi’s second term is his final one. Part of the problem with the Mubarak model is that people understandably become restless with any leader, no matter how effective, after too many years in power. Egypt might well have been spared the travails of the political eruption in 2011 if there had been a regular succession within the ruling party. If any single Egyptian leader, including President Sisi, becomes too closely identified with the status quo, another political uprising is eventually likely.

Conclusion

One can make a case that successful democratic elections often need to proceed from a firm base of at least moderate economic prosperity and social modernity. Tunisia is an example, albeit a fragile one, of an Arab democratic polity, slowly taking shape in tandem with relative economic and social progress – unlike the situation in Egypt.

But this does not mean that the Egyptian elections are a completely hollow exercise. As long as insightful and courageous observers like Mr. Atef can analyze and comment upon them, then there is hope that over the longer term, a freer political process can evolve as economic and social conditions improve.