Nothing captured the imagery of change in the Middle East more than last year's demonstrations in Tahrir Square that brought down Hosni Mubarak, Egypt's president for 30 years. The sense of hope and possibility that seemed so alive in Tahrir Square made everyone in the Middle East believe there truly was going to be an Arab Spring.

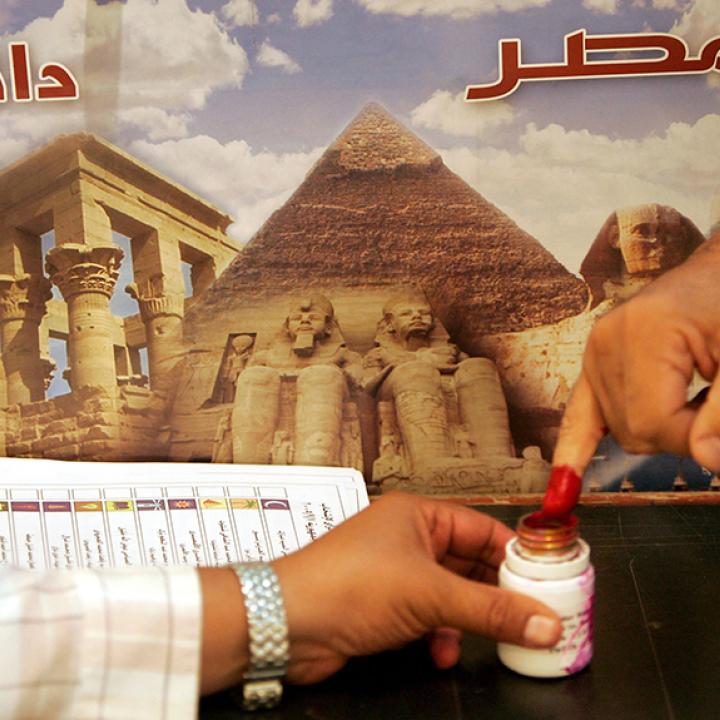

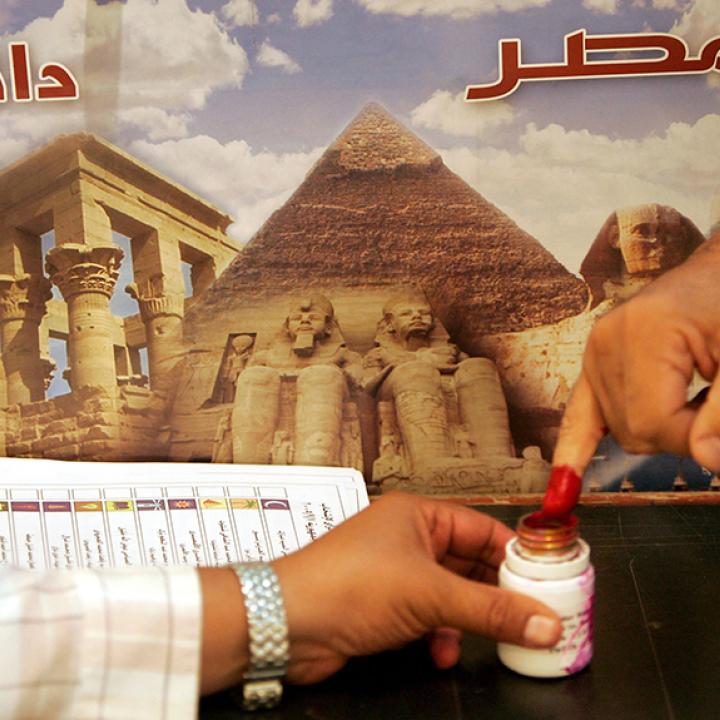

What a difference a year makes. With Egypt's economy in free fall, with a new constitution still not written, with security generally lacking, and with the recent presidential elections producing a runoff this weekend between an uninspiring Muslim Brotherhood candidate and an official who appears to be a remnant of the Mubarak regime, the mood of optimism has soured in Egypt -- as well as in the U.S., with some potentially troubling consequences.

But the euphoria over the Arab Spring was always misplaced and unrealistic. Change needed to come to the Middle East and was bound to do so sooner or later. The speed of the awakening triggered by the Facebook generation just masked the inevitability that satisfying a growing sense of indignity and injustice was always going to take time and, at the outset, was almost certain to favor the Islamists.

MUBARAK FAILINGS

How did we arrive at this point? Leaders such as Mubarak denied secular forces the ability to organize and create an alternative -- especially to his rule. But the one place Mubarak could not take on was the mosque, where one was free to speak, organize, provide social services and embody social justice.

When Mubarak was pushed out, there was a vacuum politically, and the Islamists were most equipped to fill it. Secular alternatives were not. They were neither organized nor had clear identity or purpose. Worse, they had few ties to lower, impoverished classes in a country that is deeply religious.

So the U.S. is faced with either the Muslim Brotherhood or a member of the old Mubarak regime. What might the future look like? Islamists -- the Muslim Brotherhood and the even more extreme Salafis -- captured two-thirds of the seats in the parliamentary elections. But they have done little to prove that they are capable of improving the quality of life or taking on any of Egypt's challenges.

Today, it is not clear who retains credibility. The military has managed the transition to civilian rule poorly. Neither candidate, Mohamed Morsi, who comes from the Muslim Brotherhood, or Ahmed Shafiq, whose career was spent in the military, speaks of challenging the military and its prerogatives. And though the military is declaring that a Constitution must be drafted soon or it will offer an interim one to define the powers of the president, whoever is elected will face daunting challenges with authority that remains to be determined.

WHAT MIGHT BE AHEAD

To be sure, if Morsi is elected, the Brotherhood will control both the presidency and the parliament. The group has an anti-Western, anti-Israeli, pan-Islamic ideology. It is a highly disciplined organization with a dictatorial bent that believes Islam must be at the center of all life, including political life. Would its members recognize that Egypt's urgent economic needs require help from the outside and unity on the inside? That is an unknown.

Shafiq, the other candidate, is secular. He was appointed prime minister by Mubarak in his waning days. He is far less likely to alter Egypt's approach toward the region and the world and, having effectively run Egypt's national airline, might have a better appreciation of what is required economically. But would order be more important than reform for him? No one really knows.

At this point, the odds of Morsi winning are probably greater given the superior organization of the Brotherhood and because leading secular figures of the revolution are backing him out of fear that Shafiq will undo the revolution. That said, the longing for law and order could yet produce a surprise Shafiq victory. The parliamentary and presidential elections have been basically free and fair.

Though the U.S. might have a strong stake in Egypt remaining committed to peace, fighting terror and being a source of stability in a rapidly changing Middle East, it is not America that will determine Egypt's future -- Egyptians will. We can hope that Egyptians, seeing themselves as citizens and no longer as subjects, will insist that any government elected needs to deal with Egypt's problems and be accountable to them. And we should make our views clear even before the election runoff that we are very willing to help Egypt deal with its problems.

But we make our own choices, and our decisions will depend on Egypt's behavior. For the U.S. to provide material and financial support to the new government, Egypt must respect the rights of minorities and women. It must permit basic rights of free speech and assembly and ongoing political competition to ensure repeatable elections. And it must fulfill its international and treaty obligations, including its peace treaty with Israel.

These basic ground rules for our support should be stated very clearly now -- before the runoff. If Egypt's new leaders are not prepared to play by these rules, they -- and the Egyptian public -- should be aware of the consequences before they go to the polls this weekend. Whatever they decide, our response should not come as a surprise to them.

Dennis Ross is counselor at The Washington Institute and former special assistant to President Obama.

USA Today