- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

Will Qatar's Diplomatic Exile Spark the Next Great War?

The Sunni Gulf powers have long been spoiling for a fight with Iran, and this could be just the excuse they need.

Sarajevo 1914, Doha 2017? We could be at a historic moment akin to the assassination of the heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which resulted in what became known as the Great War. This time, though, the possible clash is between a Saudi-United Arab Emirates force and Iran. Washington is going to have to act quickly to stop the march to war, rather than wait for the carnage to begin.

The nominal target of Saudi Arabia and the UAE is Qatar, which has long diverged from the Arab Gulf consensus over Iran. Riyadh and a growing list of Arab countries broke ties Monday with the gas-rich emirate, and Saudi Arabia announced that it had halted permission for Qatari overflights, closed the land border, and banned ships bound for Qatar transiting its waters. This is a casus belli by almost any definition. For perspective, the Six-Day War, which occurred 50 years ago this week, was prompted by Egypt's closure of the Straits of Tiran, thus cutting off Israel's access to the Red Sea. In response, Iran reportedly announced it will allow Qatar to use three of its ports to collect the food imports on which the country is dependent -- a gesture that Riyadh and Abu Dhabi will probably see as only confirming Doha's treacherous ties with Tehran.

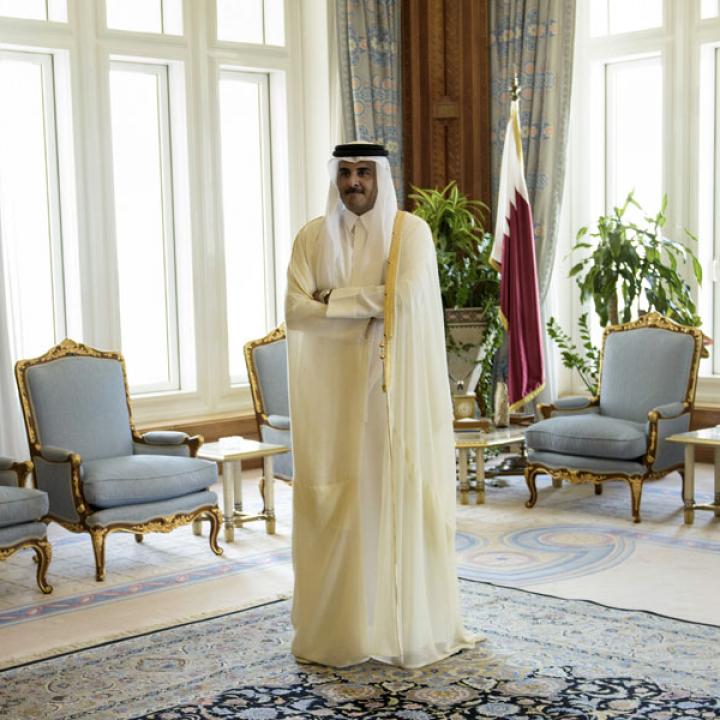

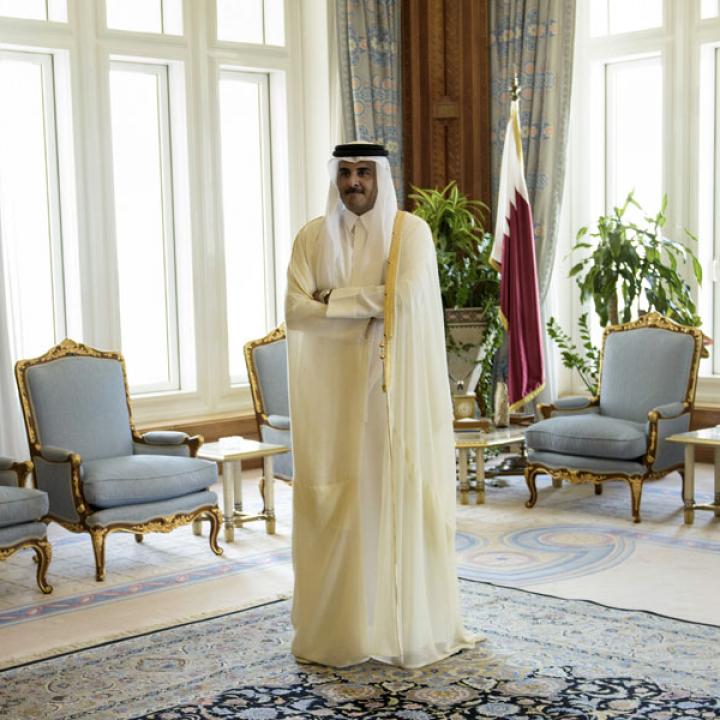

There are at least two narratives for how we got here. If you believe the government of Qatar, the official Qatar News Agency was hacked on May 24 and a fake news story was transmitted quoting Emir Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani as saying, "There is no reason behind Arabs' hostility to Iran." The allegedly false report reaffirmed Qatar's support for the Muslim Brotherhood and its Palestinian offshoot, Hamas, as well as claiming Doha's relations with Israel were good.

The government-influenced media in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, meanwhile, adopted an alternative narrative, treating the news story as true and responding quickly with a burst of outrage. The emir's comments were endlessly repeated and, to the anger of Doha, internet access to Qatari media was blocked so that the official denial could not be read.

There is a possibility that the initial hacking was orchestrated by Tehran, which was annoyed by the anti-Iran posture of the May 20-21 summit in Riyadh, when President Donald Trump met King Salman bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud and representatives of dozens of Muslim states. On June 3, the Twitter account of Bahraini Foreign Minister Sheikh Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa was hacked for several hours in an incident his government blamed on Shiite opposition activists, rather than pointing the finger at Iran. Iran's motive would be to show Gulf disunity -- as well as its irritation with Trump's endorsement of the GCC stance against Tehran.

For its part, Qatar sees itself as a victim of a plot by Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, which have had a traditionally antagonistic relationship with Doha despite the shared membership in the Gulf Cooperation Council. Riyadh views Qatar -- which, like the kingdom, gives Wahhabi Islam a central role -- as a regional troublemaker. Doha, which allows women to drive and foreigners to drink alcohol, in turn blames the Saudis for giving Wahhabism a bad name. Meanwhile, Abu Dhabi despises Doha's support for the Muslim Brotherhood, which is banned in the UAE.

Although there was an awkward eight-month diplomatic hiatus in 2014, the root of today's trouble harkens back to 1995, when Emir Tamim's father, Hamad, ousted his increasingly feckless and absent father from power in Doha. Saudi Arabia and the UAE regarded the family coup as a dangerous precedent to Gulf ruling families and plotted against Hamad. According to a diplomat resident in Doha at the time, the two neighbors organized several hundred tribesmen for a mission to murder Hamad, two of his brothers, as well as the ministers of foreign affairs and energy, and restore the old emir. The UAE even put attack helicopters and fighter aircraft on alert to support the attempt, which never actually happened because one of the tribesmen betrayed the plot hours before it was to take place.

With such events as background, any paranoia on the part of Emir Tamim may be justified. Over the weekend, a UAE newspaper reported that an opposition member of Qatar's ruling al-Thani family, Sheikh Saud bin Nasser, intended to visit Doha "to act as mediator."

With just 200,000 or so citizens, it can be hard to explain the importance of Qatar. Foreigners living there sometimes regard it with bemusement. The Doha skyline at night is dominated by often-empty though lit-up skyscrapers, one of them nicknamed, because of its shape, "the pink condom." Yet, Qatar has the planet's highest per capita income. After Iran, the emirate boasts the largest natural gas reserves in the world and is a huge exporter to markets stretching from Britain to Japan. It also is host to the giant al-Udeid Air Base, from which American aircraft flew combat operations during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and which is a command center for the U.S. campaign against the Islamic State.

For the 37-year-old Emir Tamim -- who rules in the shadow of his father, who abdicated in his favor in 2013 -- the key priorities are probably to remain a good U.S. ally while not doing anything to annoy Iran. His country's gas wealth is mostly in a huge offshore field shared with the Islamic Republic. So far, the Qatari drinking straw has taken more out of this hydrocarbon milkshake than Iran has.

Washington can play an important role in defusing this potentially explosive situation. U.S. officials may believe that Qatar was being less than evenhanded in its balancing act between the United States and Iran -- but a drawn-out conflict between Riyadh and Doha, or a struggle that pushes Qatar into Tehran's arms, would benefit no one. In this respect, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is arguably well-placed. ExxonMobil, where he was CEO before joining the U.S. government, is the biggest foreign player in Qatar's energy sector, so he presumably knows the main decision-makers well.

Riyadh and the UAE also seem to be establishing their bona fides as alternative sites for the U.S. forces now at al-Udeid. Their credentials are not as good as they might argue. In 2003, Saudi Arabia pushed U.S. forces out of Prince Sultan Air Base, as Riyadh tried to cope with its own Islamic extremism in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Abu Dhabi already hosts U.S. tanker and reconnaissance aircraft, but it would take time to establish a fully equipped command center to replace the facility at al-Udeid.

The confrontation marks a test for Trump's young administration. It was only weeks ago when, at the photo-op in Riyadh, Emirati Crown Prince Muhammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan shouldered aside Emir Tamim so he could be at the U.S. president's right hand. Now, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are trying to do the same thing on the international stage. Of all the possible Middle East crises, Trump's advisors probably never mentioned this one.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Gulf and Energy Policy Program at The Washington Institute, and coauthor of its 2017 Transition Paper "Rebuilding Alliances and Countering Threats in the Gulf."

Foreign Policy