- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Muslim Thinkers to Face the Problematic New “Theology of the Jews” (Part 1)

In the course of the past century, a troubling development has asserted itself in Islamic thought. Whether in scholarly religious texts or in popular presentations, a new Islamic “theology of the Jews” has coalesced into a thorough demonization of both historical and contemporary ‘Jews.’ In this evolving and radicalizing theological outlook, “the Jews” are presented as a unitary, undifferentiated collective. This collective is portrayed not only as political foes or religious rivals, but as the quintessential nemesis—with the corresponding struggle shaping the course of history and fulfilling prophecy.

While the universe of Islamic thought is wide, encompassing diverse trends and displaying multiple, often conflicting, expressions on any given subject, the problematic aspect of the new pejorative “theology of the Jews” is that it has been virtually unchallenged. Islamic portrayals and assessments of “the Jews” are almost invariably negative. In the rare instances where an ‘excess’ is noted—such as among the few intellectuals that reject the authenticity of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion—the rationale for qualifying this negative portrayal is that such excesses obfuscate the ‘real’ grounds for criticism. With scant attempts to see Jewish history and society as complicated and diverse, the trend toward enmity has also assimilated and appropriated Western antisemitism while leveraging anti-Zionism as a baseline and an entry point.

It is true that some distinction is occasionally (and defensively) made between the categories of Zionist, Israeli, and Jewish in sophisticated intellectual circles in the Arab world. Statements on this point stress that the enmity is not with the Jews as a religious group, and that a settlement for peace should ultimately be achieved with the Israelis as a national community. These intellectuals insist that the enemy is instead the Zionists, whose expansionist ideology denies Palestinian national rights and espouses racist convictions while branding any attempts to criticize Israeli politics or Zionism itself as “anti-semitic.”

Yet when contrasted with the broader and deeply seated demonization of the Jews that also exists in the Arab world, these statements seem to oscillate between wishful denial and intellectual dishonesty. Anti-Jewish rhetoric is the overwhelming norm in Arab cultural, political, and popular discourse. The distinction between “Jewish,” “Israeli,” and “Zionist” is seldom made in either popular or elite discourse and, if mentioned at all, is often added as an after-thought. Even the few instances of a tacit willingness to align with Israel, such as in the pursuit of a anti-Iranian coalition, are partially motivated by an assumption that “the Jews” hold disproportionate influence and power that can be leveraged. Not unlike some Western contexts, there seems to be a fine line in these cases between philo-Jewish and anti-Jewish sentiments.

The roots of this discourse must be understood as feeding both into and from a new but expanding Islamic “theology of the Jews.” As such, the pursuit of any meaningful resolution for the Middle East conflict will be hampered, if not outright denied, without a genuine effort on the part of Muslim intellectuals to address and dismantle this newly dominant radical theology.

This is not a call for religious reform, or for the enactment of Vatican II style reconsiderations, since the framework to challenge this new trend already exists within Islamic theology itself. The task at hand is instead to counter a recent set of developments, which, if continued to be left unchallenged, have the potential of causing lasting damage to longstanding traditions of Islamic theology while aligning with fringe Western antisemitism.

The modern pejorative Islamic “theology of the Jews” is based on three interlocking trends: an abandonment of the longstanding Islamic principle of non-differentiation between non-Islamic “Divine” faiths, an amplification of the value and implications of traditions and events regarding certain episodes from the formative phase of Islam that involve Jews previously deemed marginal; and an equation between religious parables and assumed historical chronology to promote a reductionist model of history in which “the Jews” are ascribed an ongoing negative role. This first trend is discussed below, while the second two are discussed in a separate article.

The Abandonment of Non-Differentiation: Separating Jews from ‘Ahl al-Kitaab’

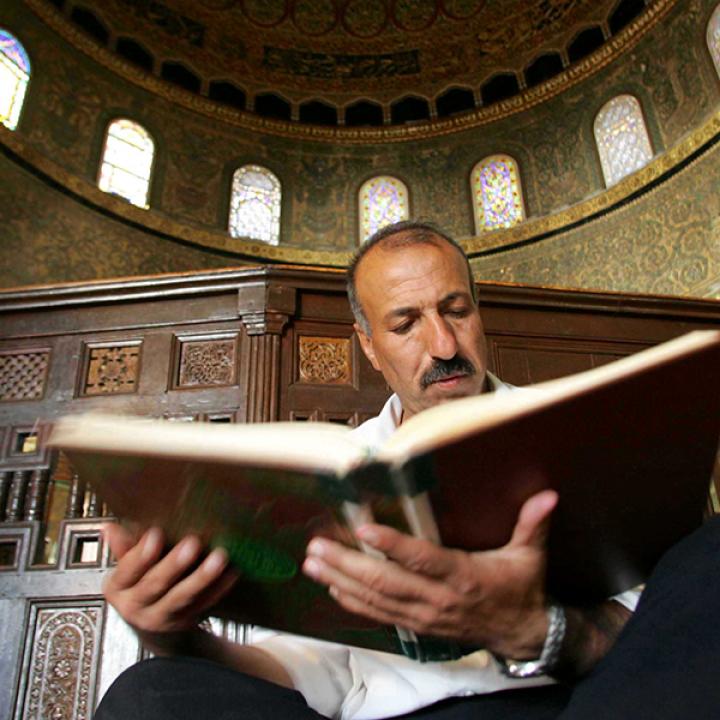

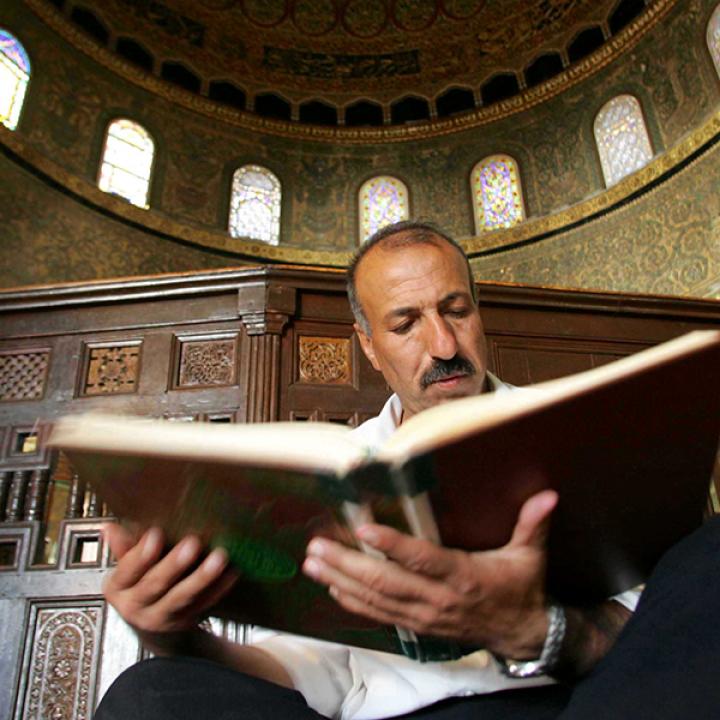

Jews as a collective figure prominently in the foundational texts of early Islam, where they are known as al-Yahud (the Jews) or Banu Isra’il (the tribe of Israel). While Muhammad in the Qur’an is called the “Prophet of the Nations” (al-Nabi al-Ummi), he is presented in particular as fulfilling the lineage of the prophets of Israel. In turn, these prophets are all characterized as preachers of Islam—the perpetual Divine religion. It is Moses, not Muhammad, to whom the Qur’an makes the most references. Similarly, the Qur’anic text is replete with accounts of the Biblical Israelites—most often explicitly as archetypal examples of renegades against the call of the prophets and the will of God. The Qur’an also records Muhammad’s polemics with the contemporary Jews of the city of Yathrib, where tradition reports that Muhammad had settled as an arbiter, then leader. The substance of much of these arguments with the “Yahud” is their rejection of Muhammad’s status as Divine messenger despite presumed references to Muhammad in their own texts.

In both cases, the Qur’an maintains a critical tone towards ‘the Jews,’ and is occasionally more charitable towards Christians. Even so, later Islamic treatises in comparative religions generally establish that there is less doctrinal distance between Islam and Judaism than with Christianity. The concept of the Trinity, deemed polytheistic, establishes a dogmatic rejection of Christianity as theologically in error. On the other hand, despite an opaque reference in the Qur’an to a Jewish infringement on monotheism (suggesting Jews view Uzayr—possibly Ezra—as the “son of God”), it was accepted by classical exegetes and scholars that though Jews’ deviated in their rejection of Muhammad, they were not—as the Christians were—in theological error.

The implications of this distinction, though marginal, continues to manifest in some practices today. Among Muslims in Western settings, Jewish Kosher butchering is recognized as adhering to a more restrictive set of rules than Muslim Halal requirements, and Kosher meat is thus permitted for consumption.

Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of scholastic treatises by Islamic scholars classify both Jews and Christians under the non-differentiated category of Ahl al-Kitab—followers of preceding faiths made obsolete with the coming of Muhammad’s prophesy. In contrast to the theological rejection of polytheism in Islamic-controlled territories, incorporating the Ahl al-Kitab into an Islamic polity is acceptable, though regulated by restrictive measures and with the understanding that they occupy a subordinate status. In line with these theological precepts, Jews, Christians, and a few other communities have been granted the same margins and suffered the same restrictions throughout the course of pre-modern Islamic history.

Yet in the last century, this principle of non-differentiation has been abandoned. And while the advent of Zionism as a national movement seeking the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine certainly contributed to and accelerated the differentiation between Jews and Christians in Islamic thought, the beginnings of this distinction can be traced to populist formulations—phrased by both Christian and Muslim intellectuals—predating the conflict over Palestine.

In the late 19th century, as intellectuals perceived an environment of receding primacy for religion, the Arab nationalist version of the “Ummah” redefined the concept from its original theological meaning as a community of Muslims regardless of ethnic background to one of Arabs, whether Muslim, Christian, or other. Yet this new nationalist formulation reflected a reluctance and, ultimately, failure to incorporate the Jews of the Arab lands into the broader notion of Arab community.

As Jewish presence in Palestine increased, the pitch of the Arab nationlists’ efforts to differentiate Arab Jews intensified. Antoun Saadeh—founder of the influential pan-Arab Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP)—attempted in his book al-Islam fi Risalatayhi (Islam in its Two Messages) to reframe Middle Eastern history by presenting both Christianity and Islam as reflections of the region’s ethos and genius. In parallel, he advanced the paradigmatic statement that “none challenges us in our land and our history other than the Jews.”

Saadeh was a secular thinker of Christian background. Yet while his bold statement may have been a product of his intellectual universe, its substance quickly emerged as the new norm. A number of Islamic authors began to engage in a sustained effort to document and demonstrate Jewish perfidy towards Islam and to underline the need to strengthen the Islamic enmity towards the Jews. Early works did not see any distinction between Jews, Zionists, and (later) Israelis—these terms all had unqualified pejorative connotations. This non-differentiation even necessitated the introduction of a new term—“Musawi” (Mosaic, of Moses) in certain areas to allow for non-pejorative references to local Jews.

These authors legitimated their new differentiation between Christian and Jewish Arabs through recourse to the Qur’anic text. A verse in the “al-Ma‘idah” chapter that presents opposing assessments of Jews and Christians gained new prominence. In line with the view favored by Arab nationalists, it was interpreted as confirming enmity towards the Jews while endorsing Muslim-Christian solidarity, even suggesting a distinction between Christianity and polytheism that contrasted with earlier Islamic theology. The Quranic verse (5:82) declares: “Verily, you will find the strongest in enmity to the believers the Jews and the polytheists, and you will find the nearest in affection to them those who say ‘We are Christians.”

Though Islamic jurisprudence did not elevate the status of Christians on the basis of this new emphasis, it did present opportunities to diminish the status of the Jews. Radical fatwas (scholastic opinions) proclaimed the legitimacy of the killing of Jewish non-combatants, initially on the basis of reciprocity and the imperatives of defensive jihad, and later on a sui generis basis. Statements countering these new opinions from official religious authorities trailed behind belatedly, and were virtually never framed to insist on applying the inviolability of innocent human life to Jews.

By the 1990s, the outcome of this differentiation could be seen in the name of the radical jihadist coalition announced by Usamah bin Ladin: “The Global Islamic Front for Jihad Against the Jews and the Crusaders.” The name emphasized that any enmity towards Christians was based on their aggressive behavior—when they engaged in “Crusades.” Enmity towards the Jews, on the other hand, required no qualifications.

In the decades since bin Ladin made this distinction, there has been a hardening of the radical position towards Christians. More contemporary references to Q 5:82 tend to be limited to the sura’s first half, omitting the kinder portrayal of Christians and placing contemporary Christians under the category of ‘polytheists.’ Radicals now claim the “affinity” with Christians was restricted to the time of the Prophet (Khass), even as the first half (‘Am) remains applicable in the modern period. However, while Jihadists reinterpret these words as a commandment to practice enmity towards both Jews and Christians, the modern differentiation of Jews has remained, present in both extremist theology and wider discourse.

Moreover, this new “theology of the Jews,” favored particularly by extremists throughout the Arab world is obsessed with defeating and eradicating the Jews because they are presented, as a group, as the eternal enemy of God, the agency of evil throughout history, and a source of treachery and deceit.

To develop their point, these Islamic thinkers have also incorporated classic Western antisemitism into their rhetoric. Along with references to Islamic theological texts, they have drawn on conspiracy theories positing a Jewish plan to control the World—in order to impose a two-tier universal religion (Israelite/Noahide). Capitalism and communism, the French and Bolshevik revolutions, the economic crises, the promotion of homosexuality, multiculturalism, and debauchery in general are all explained as part of a Jewish grand plan for control. Both The Protocols and truncated, and in some cases totally fabricated, passages of the Talmud are used to substantiate these claims.

These radical views, even when not espoused by the mainstream, are able to define the narrative due to a lack of resistance or alternative views, thereby allowing it to propagate its tenets in the wider culture. Ultimately, this has empowered homicidal and genocidal impulses against Jews, even if Israeli diligence has been able to ward most of the danger against the largest physical concentration of Jews in the Middle East.

Incremental steps toward reinvigorating Muslim perspectives that insist on the humanity of Jews are appearing―such as the invitation extended by Mohammed Al-Issa, a close associate of the Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman and head of the Saudi-based World Muslim League, to Holocaust survivors for a January 2020 visit to the Kingdom. However, such top-down stances without the support of broader scholastic and intellectual output, can be critiqued as largely political, with little permanent traction in popular culture. They may provide some symbolic solace, but they do not amount to a serious debate that can substantively challenge cultural and theological anti-Jewish attitudes.

The “Jewish Question” in Arab culture is vastly different from the one that Europe faced in the nineteenth century. The actual victim in this case are the Arabs themselves, with many trapped in an obsession that interdicts their ascension to a culture of universal values. Directly addressing the corrosive “theology of the Jews” is an act of courage, but is also necessary. There are few tasks facing Arab intellectuals more important than deconstructing this recent yet pervasive affliction. It may be possible to agree with the adherents to this perverse theology that it is indeed time to free the Islamic and Arab mind of the “Jews.” The “Jews” in question, however, are not the Jewish population of Israel and the Jewish communities across the world, but the demons that this distorted world views has created at the detriment—moral, intellectual, and physical—of the Arab and Islamic population it claims to defend.