- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Contextualizing Jihad and Takfir in the Sunni Conceptual Framework

The concepts of jihad and the charge of unbelief on a Muslim or non-Muslim known as takfir have evoked mixed and dreaded reactions among many in Western countries, where the concepts often make headlines and are presented without context to those who may not have personal interactions with mainstream interpretations of Islam.

In the context of public discussion in the United States and Europe, jihad and takfir have in some cases become equated with “holy war” and decapitation of “infidels” respectively. Yet these perceptions are grounded in the assumption that the terms as defined by terrorist groups also reflect broader Sunni and Shi’a conceptions of the concepts. This mischaracterization both hinders the public understanding of Islam as a multifaceted religion and U.S. security understanding of terrorist threats motivated by specific and extremist concepts of jihad and takfir.

Jihad in the Earliest Years of Islam

In Arabic, the word “jihad” broadly means “to strive” or to make a “determined effort,” and a Mujahid is someone who strives or engages in jihad. Jihad is often expanded to the term jihad fi sabil Allah (jihad in the path of God) to distinguish the term from pre-Islamic usage and to assert that the “determined effort” is carried out in accordance with God’s divine mandate. However, the specifically religious connotations of the word have different shades of meaning even in the Koran, where the connotation of jihad shifts along with the changing sociopolitical environments under which Prophet Muhammad developed Islam.

During Islam’s earliest ‘Meccan’ period, the Prophet Muhammad’s message of jihad focused on propagating Islam against a prevailing order more or less characterized by idolatry, paganism, and polytheism. Following the Prophet’s forced hijra (migration) from Mecca to Medina in 622 and the consolidation of his umma (community of believers), jihad took an activist sense dedicated to both defending and expanding the religion. Already, the earlier “passive” jihad of the Koranic Meccan verses contrast with the “active” and/or “aggressive” sense of jihad in the Koranic Medinan verses.

Consequently, jihad developed into conceptions of both inward and outward struggles. According to an often repeated (though not universally accepted) hadith, or recorded sayings of Prophet Muhammad, jihad could be a struggle against one’s sinful proclivities, also known as “greater jihad”, or a struggle against injustice, known also as “smaller jihad.” Significantly, many references to jihad in the hadith collection Sahih al-Bukhari assume jihad to mean armed action.

The expansion of Islam during the Umayyad (661-750) and Abbasid (750-1258) dynasties gave rise to a conception of jihad as a form of warfare, related to the division of the world into Dar al-Islam (Abode of Islam) and Dar al-Harb (Abode of War). Jurists envisioned perpetual warfare between Muslims and non-Muslims until Dar al-Islam prevailed under the establishment of religiously legitimate Muslim rule, whereby Islam superseded other faiths and created a just socio-political order.

In this context, jihad developed offensive and defensive forms. Offensive jihad aimed at expanding the territory of Islam as a collective duty. Jihad did not, however, imply conversion by force—the Koran specifically states that “there is no compulsion in religion.” Defensive jihad made it an individual duty for every Muslim to resist foreign aggression. Notably, jurists did not expect Muslims to wage endless war in either case, and allowed for truces and peace treaties with other parties.

With the 1258 defeat of the Abbasid Caliphate by the Mongolian leader Hulagu and the Mongolian elite’s subsequent conversion to Islam, jihad further transformed in some interpretations into a sanction of revolt against nominally Muslim rulers. The medieval scholar Ibn Taymiyyah affirmed that it was permissible to rebel against a ruler who fails to enforce Islamic law, concluding that jihad against the Mongols was acceptable as superficial Muslims who did not govern according to Islamic law. Arguably, Ibn Taymiyyah’s conclusion marks a rift in views on when jihad is acceptable—from the fourteenth century onwards, whereas mainstream Islam continued to promote submission to political authority as a means to prevent fitna (strife) within the umma, dissident scholars sanctioned jihad against a corrupt ruler even within Dar al-Islam.

In sum, jihad in premodern times had, depending on the context, referred to a) an obligatory effort to defend and/or expand the abode of Islam; b) an essential feature to dispense with corrupt rule; and c) a self-regulatory means to promote individual welfare. This multivalence of jihad has only deepened in the past century, initially developing as a response to colonial governments.

The Jihad of Anti-Colonialism

Against the backdrop of early Islamic anti-colonial movements, the Sunni Indian-Pakistani jurist Abu Ala Mawdudi (1903-79) sharpened the definition of jihad as a movement of liberation throughout the world to allow Islam to reign supreme and furnish justice for all. Mawdudi wrote:

Islam requires the earth—not just a portion, but the whole planet—not because the sovereignty over the earth should be wrested from one nation or several nations and vested in one particular nation, but because the entire mankind should benefit from the ideology and welfare programme or what would be truer to say from ‘Islam’ which is the programme of well-being for all humanity. Towards this end, Islam wishes to press into service all forces which can bring about a revolution and a composite term for the use of all these forces is ‘Jihad’.

Thus, jihad became under this definition an all-embracing world revolution. Mawdudi also reinterpreted the term jahiliyah so as to fit with his world revolution: originally used to refer to pre-Islamic Arabia, it became any time or place in which the Islamic state has not been actualized. In other words, Mawdudi split the world between a divinely-ordained Islamic world and a jahili (infidel) world to be overtaken through jihad. As such, Mawdudi’s jihad required employing all possible means and forces to about a universal all-embracing revolution leading to his vision of an Islamic world.

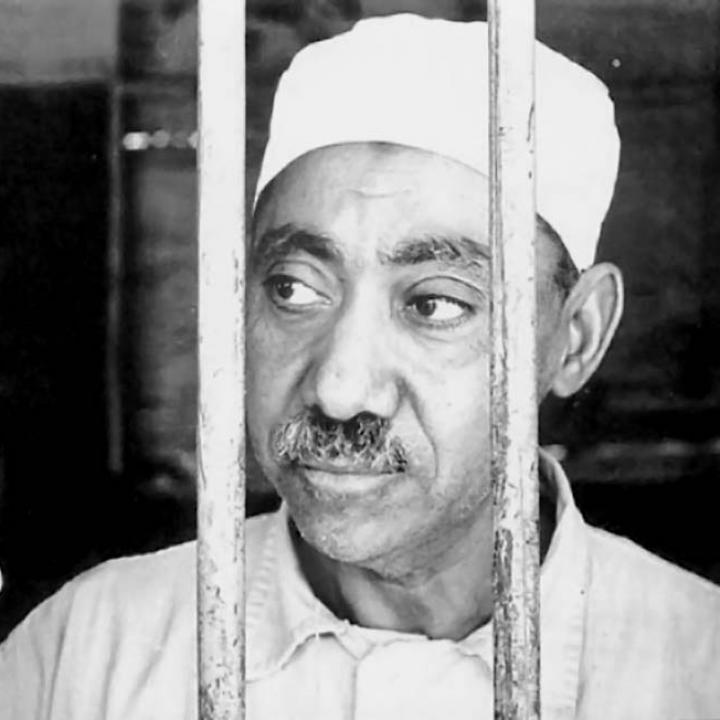

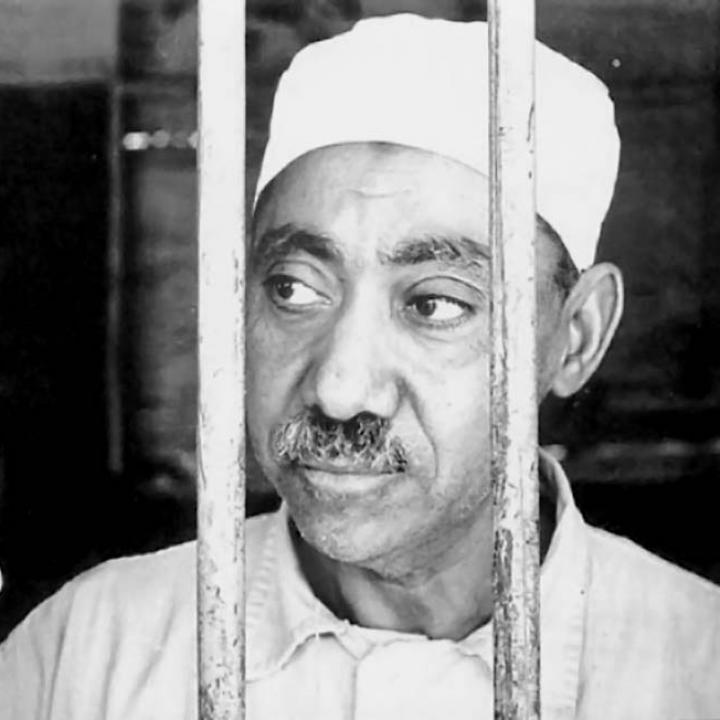

Significantly, Mawdudi’s divinely ordained world excluded the Shi’a. In his book Ar-Riddah bayn al-Ams wal-Yaum (Apostasy in the Past and the Present) the author labels them as non-believers, stating that even the Imami Ja'fari Shia, "despite their moderate views (relative to other sects of Shi’ism), they are swimming in disbelief like white blood cells in blood or like fish in water." Two Muslim Brotherhood leaders—Hasan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb—would build on this interpretation of jihad and its emphasis on establishing an Islamic state.

Sayyid Qutb and the Islamism of the Muslim Brotherhood

Qutb drew on both Mawdudi and Ibn Taymiyyah to argue that a state of jahiliyah dominated any Muslim society living under corrupt rulers. Therefore, righteous Muslims have a duty to bring about God’s sovereignty (hakimiyah) over society. Qutb perceived the entire modern world as steeped in jahiliyah, stating:

If we look at the sources and foundations of modern ways of living, it becomes clear that the whole world is steeped in Jahiliyyahh, and all the marvellous material comforts and high-level inventions do not diminish this ignorance. This Jahiliyyahh is based on rebellion against Allah's sovereignty on earth. It transfers to man one of the greatest attributes of Allah, namely sovereignty, and makes some men lords over others.

According to Qutb, this modern jahiliyah required the same treatment as the Prophet’s uprooting of the original jahiliyah and its replacement with an Islamic state. This mid-century argument represents a radical departure from the longstanding traditional view of leadership. Under this framework, Muslim leaders become unbelievers/takfir [kuffars] by virtue of their impiety, and must be excommunicated from society. Qutb denounced the extant leadership of the Arab world and rejected their claims to either Islam or political power.

Qutb then professed that under current circumstances, jihad was legitimate and justified against said leadership. Throughout his writings, particularly Milestones (ma’alim fi tariq), Qutb reinterpreted traditional Islamic concepts to legitimize a violent takeover of the state. His unique conception of jihad thus became a central component of his overall ideology as the catalyst to reinstate God’s sovereignty over mankind through political transformation. It is this expansive definition of jihad that has influenced most subsequent radical Sunni groups and sparked a number of modern religiously-driven efforts for political change.

For example, the assassins of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat justified jihad against corrupt and/or superficial Muslim rulers and the imperative of establishing an Islamic state in their pamphlet Al-Faridah al-Gha’ibah (The Neglected Duty). Its author Muhammad Abd al-Salam Faraj argued that leading Muslim scholars had neglected jihad, and that “there is no doubt that the idols of this world can only be made to disappear through the power of the sword.” Faraj drew on the writings of Ibn Taymiyyah and Ibn Kathir, among other sources, to contend that jihad as armed action is the cornerstone of Islam. He also declared that rulers who “do not rule by what God sent down” are kuffars (unbelievers) and apostates. He called on Muslims to exert every conceivable effort to establish the Islamic government, restore the caliphate, and expand the abode of Islam.

According to the line of thought established by Mawdudi, Qutb, and Faraj, Sunni Islamists transformed the context and regulations against which jihad was to be carried out, mandating jihad—previously a concept bound to communal obligations—into an individual obligation for all Muslims. These views ran directly in the face of mainstream Islamic thinkers’ emphasis on submission to political authority, regardless of how the state is governed, and the circumscribing of jihad as an aggressive action only in the case of its declaration under specific conditions by a legitimate and recognized Islamic ruler of state (caliph).

The Centralization of Jihad in Jihadi Salafism

While traditional definitions of jihad continued to hold sway for many Muslims, the new expansion of jihad’s role in Islam developed in strains of the puritanical Salafi school of Islam, which seeks to create a utopian Islamic state by returning to the authentic beliefs and practices of the first generations of Muslims—the “righteous ancestors.” It was these strains that influenced Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri. Bin Laden developed Qutb’s focus on colonialist structures into his fury at the “blatant imperial arrogance of the United States,” especially during its involvement in Saudi Arabia—the cornerstone of the Islamic world. Bin Laden addressed his message to Muslims throughout the world, expanding the interpretations that had developed in the Arabian peninsula into a numerically small yet global movement.

Thus, certain Salafists developed a doctrine emphasizing the primacy of jihad. These “Salafi-Jihadis” assert that only jihad in the path of Allah can bring about an Islamic state. In contrast, quietist Salafism seeks to create the Islamic state through education and indoctrination of individuals, as seen in the Wahabi model of Saudi Arabia. Activist Salafis work within existing political systems to bring them closer to an idealized Islamic state, as modeled by the Muslim Brotherhood’s previous engagement with elections in Egypt. While each strain seeks the broader implementation of an Islam based on their own views, only Salafi-jihadis use a violent version of jihad in an attempt to actualize these ends.

Jihad as Terrorism Comes to the Fore

However, violence has allowed jihadi Salafism to create an outsized visibility of their worldview internationally. Al-Qaeda’s focus on the United States was designed as a means to an end: a way to reduce U.S. support of “apostate” regimes in the Middle East that prevent the creation of this Islamic state. Consequently, Bin Laden’s organization al-Qaeda and its off-shoot the “Islamic State” (IS) have both dramatically shaped public views in the Western world of what ‘jihad’ means and looks like.

IS shares al-Qaeda’s ideology, but has focused on an alternate shot-term goal—establishing a functioning Islamic government according to IS ideals. As with Faraj’s Neglected Duty, IS selectively promotes controversial verses from the Koran and citations from classical and contemporary scholars in order to legitimize its rule. In reviewing fifteen issues of the Islamic State’s Dabiq magazine issued from June 2014 to July 2016 demonstrate the continued relevance of Ibn Taymiyyah’s thought to creating a particular understanding of jihad.

Islamic State publications have also focused on promoting controversial passages of the Koran to the exclusion of other sentiments. Dabiq publications regularly cite Al-Ma’ida Number 5, Verse 51, which reads: “O you who have believed, do not take the Jews and the Christians as allies. They are [in fact] allies of one another. And whoever is an ally to them among you - then indeed, he is [one] of them. Indeed, Allah guides not the wrongdoing people.”

At-Tawbah Number 9, Verse 5 reads:

And when the sacred months have passed, then kill the polytheists wherever you find them and capture them and besiege them and sit in wait for them at every place of ambush. But if they should repent, establish prayer, and give zakah, let them [go] on their way. Indeed, Allah is Forgiving and Merciful.

Clearly, the Islamic State not only tried to justify the centrality of jihad and takfir but also relies on the concepts to develop its ideology into a religious triumphalist movement. In other words, the radicalist interpretations of jihad and takfir that began with Ibn Taymiyyah in the fourteenth century have found their conclusion in the Islamic State’s triumphalist ideology, which has dehumanized, bastardized, and “apostasied” both the Muslim and non-Muslim “Other.” Under this worldview, the “Other” has become a target for death, but observers should recognize that this concept is a religious offshoot that has been separated from the mainstream Islamic jurisprudence since the 14th century.

It is important to note that most Muslim religious establishments have condemned IS and categorically reject the organization’s interpretation of jihad, espousing instead the concept of defensive jihad exclusively. These figures also cite the Koran, demonstrating the Koran’s emphasis on the defensive nature of jihad—exemplified by such verses as chapter 2, verse 190: “And fight in the way of God with those who fight you, but aggress not: God loves not the aggressors.”

Salafi-Jihadis have allowed their disgust with the ‘Other’—anyone operating outside the framework Salafi interpretations of Islam and consequently a ‘Kufar’—to drive their declarations of jihad. In this worldview, ‘jihad’ has transformed into an expansive religious triumphalist ideology dedicated to exterminating anyone who does not subscribe to it. The expansion of this ideology has been helped both by its ability to ‘cloak’ itself in the sanctity of the sacred and the history of authentic Islam and by a reluctance of many Westerners to understand the nuances behind Salafi-jihadism that make it so dangerous.

Thus, while it is easy for outsiders to legitimate Salafi-Jihadis’ conflation of jihad with terrorism, its meaning is not nearly so specific. Jihad is a malleable concept with many potential meanings. Nevertheless, both Sunni and Shi’a extremist conceptions of jihad have had a tremendous impact on the West. While the Sunni version is a triumphalist religious ideology incapable of co-existing with Western values or societies, the Shi’a version animates regimes hostile to the West as well.