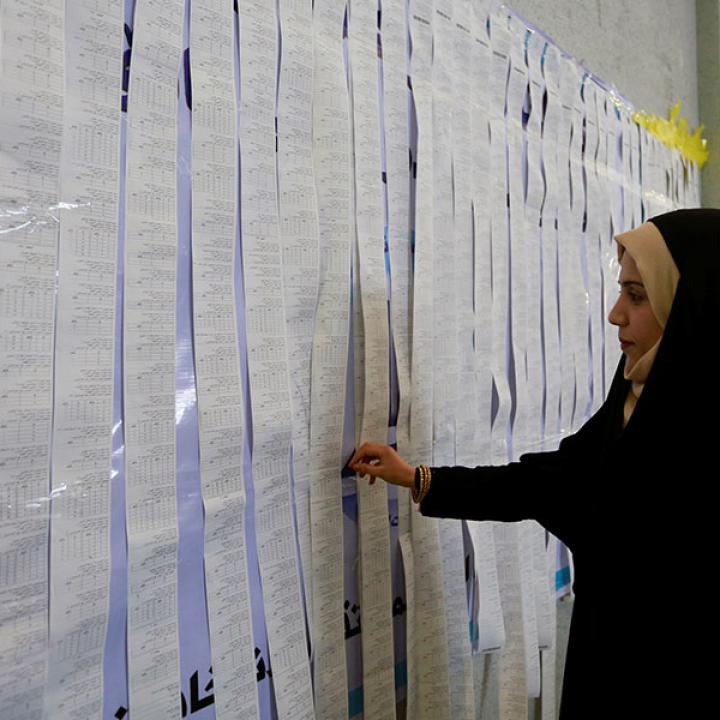

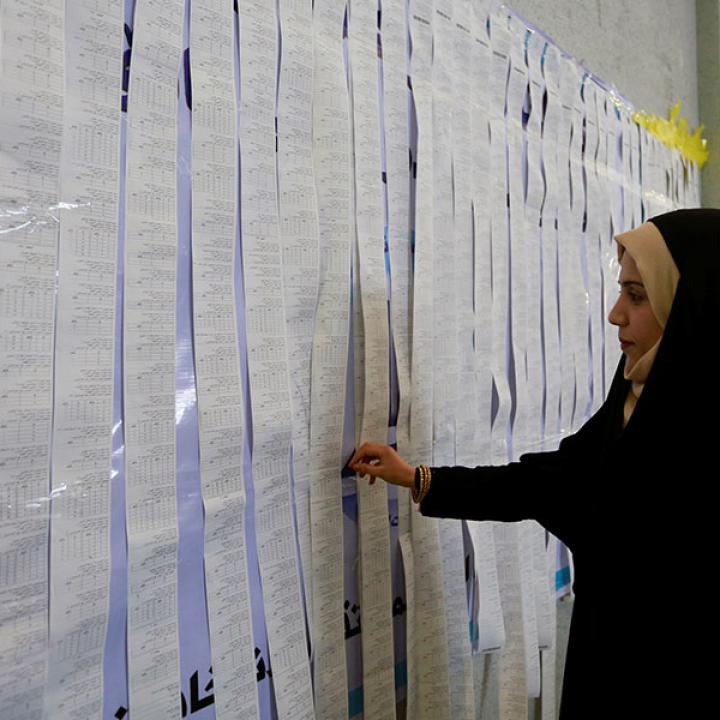

One of the remarkable things about the spontaneous mass protests in Iraq that initially erupted in October 2019 was the fact that these protesters articulated their demands without any input from or involvement of Iraq’s political parties. Instead, civil activists used social media to express opinions and expectations without directives from political leadership.

In fact, the involvement of Iraq’s political elite has been characterized by attempts to stifle the protests through killing, kidnapping, and ‘disappearing’ protesters. Aside from physical repression, the government has also periodically imposed media and internet blackouts, and Iraqi reporters in particular have been targeted by Iranian-backed proxy forces for reporting on the protests.

But this violence has backfired, and the approximately 500 Iraqi protesters killed, and the thousands more injured, forced Abdul-Mahdi to submit his resignation on November 29, 2019. Now, Iraq is caught in a political deadlock. This has been further complicated by the U.S. killing of Qassem Soleimani earlier this month, as it appeared that Qasem Soleimani was attempting to find new candidates for the position of prime minister loyal to Iran who would have been capable of winning popular approval in Iraq while continuing to support Iran’s future agenda for the region. Of course, Abdul-Mahdi’s resignation is not the ultimate end to the crisis, nor does his departure adequately address the protesters’ demands. And with the recent escalation in Iraq between Iran and the United States, the importance of leadership in Iraq has only become more clear.

And while Adel Abdul-Mahdi’s political role is technically ending, he is currently trying to appeal to Iraq’s Sunni and Kurdish political parties to support the extension of his tenure. Meanwhile, the Iraqi parliament has struggled to find a suitable successor, making it possible that Abdul-Mahdi will be re-elected into the role of Prime Minister despite his resignation almost two months ago.

It is not surprising that political elites are shying away from a new leader. The country’s great difficulties in forming a new government in the past two decades show just how difficult attempts at political reform have been in Iraq. For example, it took eight months of political deadlock in 2010 until the Erbil Agreement was reached, which finally resulted in a new government. Given the major divergences between different political currents in Iraq today, it would be very challenging for these disparate political elements to come to an agreement about the new prime minister in such a short period. But failing to find a new prime minister could plunge the country into a constitutional vacuum.

Moreover, Iraq is urgently in need of a new prime minister: someone who is popularly acceptable and who can guide Iraq through a period of transition where the Iranian role in Iraq is weakened. Much of this work requires a turn to transparency—revealing and publicizing the actions of Iranian–backed militia and their corrupt leaders inside of Iraq.

The fact that the protests in Iraq show no signs of abating demonstrates the importance of continuing political reform in Iraq rather than allowing international events to push for maintaining the status quo of Iraq’s political system. In the past two weeks, protests have actually escalated as protesters’ demands for concrete reforms by January 19 have failed to produce results. However, 2020 has also opened the door to a new potential for increased political instability in Iraq.

For example, the protests could reach the point where the government again exercises major levels of violence against them. And while Sunni groups in Iraq have by and large expressed solidarity with the protests while remaining off of the streets in order prevent the protests from being characterized as a ‘Sunni’ effort, Sunnis may become increasingly frustrated and join the protesters, focusing specifically on the Iranian-backed proxies. There is ultimately the potential for Iraq’s Sunni tribes and groups to clash directly with the militia forces in their territory, which may allow the current protesters and new allies to succeed in unifying and organizing themselves. It would be unlikely that the current government could handle such a challenge and would instead crumble.

Yet if the protesters do not articulate a clear national political program for reforms that reach all sectors of Iraqi society, it is very possible for the revolution to be hijacked. The revolutions of the Arab Spring offer a cautionary tale in how revolutions can succeed in overthrowing the regime, and yet later be hijacked by the military.

Now that Iran has lost popularity, and with the death of Soleimani, Iran’s ability to restructure the Iraqi government to its liking is less assured. Even so, if the protests continue, political forces may try to coordinate with corrupt military institutions in order to carry out a bloodless coup that would allow the current political regime to maintain power by making some cosmetic changes. This scenario made more likely by the corrupt nature of most of Iraq’s military leadership and because Islamist parties loyal to Iran have penetrated the Iraqi army.

These challenges facing Iraq raise the question of what the United States can do to ensure that Iraq returns to the original vision of a democratic Iraq. Much has been made of the United States’ continuing presence in Iraq, especially after the parliament’s non-binding vote to remove U.S. forces from the country, but America has played a deep role in shaping Iraq’s current political system as well. The United States’ overthrow of a dictatorial political system in Iraq and its attempts to create a democracy has led to numerous failures in the creation of a democratic state, and these failures must be corrected.

In order to do its part, the United States should recognize that it shares a common goal with Iraqi protesters in the reduction of Iranian influence inside Iraq. As mentioned above, one of the largest threats to the protest movement are military forces loyal to Iran, and so the United States must work to secure its partnership with nationalist Iraqi forces. Iran would like nothing better than for its proxies to push the United States out of Iraq entirely, and so the United States must not bow to this pressure, which while under the guise of Iraqis is really an Iranian attempt to secure its hegemony over another independent state. Washington must shape its commitment to Iraq with the understanding that eliminating Iranian influence and weakening its proxies in the region cannot happen if Iran succeeds in extending their control over Iraq.