- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

New Forms of Old Hate: Confronting Assad’s Anti-Semitism in Germany

Germany must recognize and seek to understand the embedded nature of anti-Semitism in Syria in order to better help its newest residents to live lives free of state-sponsored prejudice.

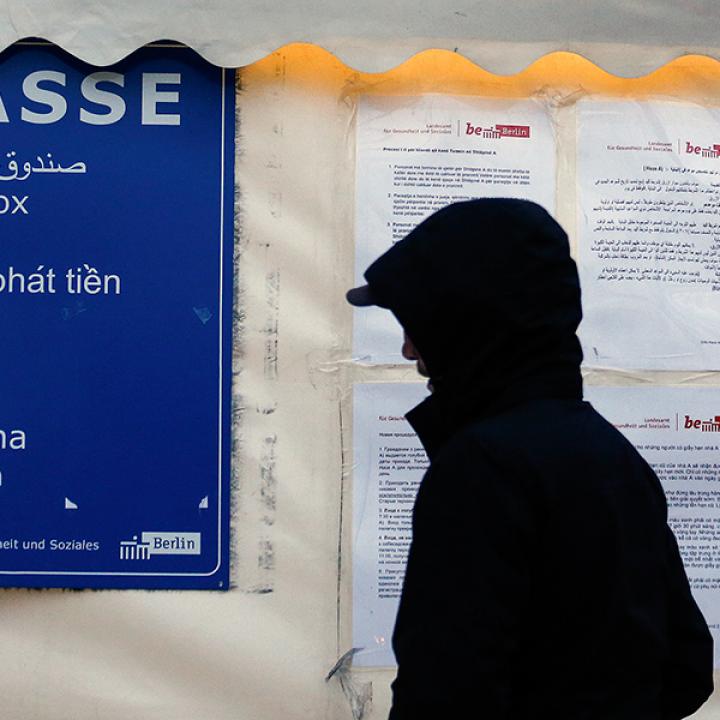

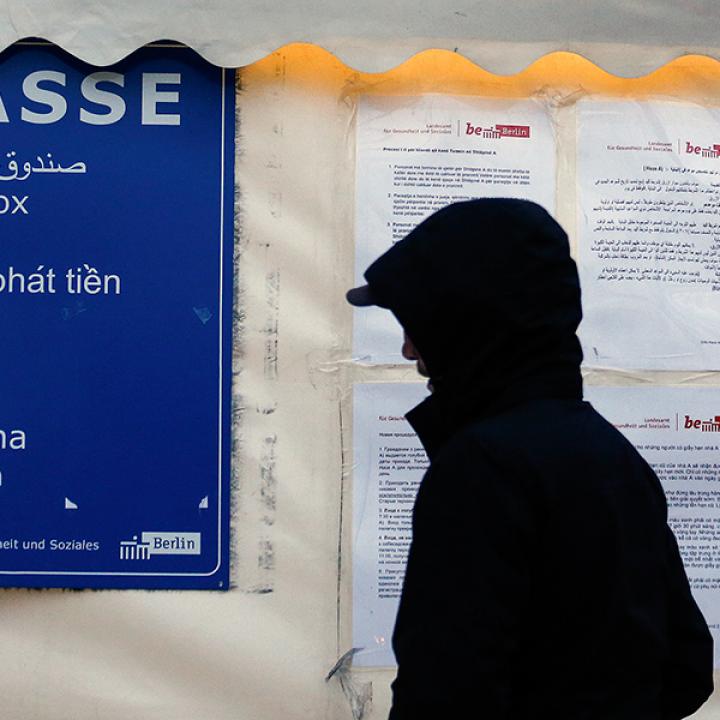

With this year’s International Holocaust Remembrance Day recognizing the 75th anniversary of the freeing of Auschwitz, it is also important for the German public to address the potential implications of a new wave of anti-Semitism within its borders. Germany’s notable acceptance of over one million refugees from Syria, where anti-Semitic propaganda has been a key feature of the Assad family’s overall messaging, has both triggered both a rise in Germany’s far-right and brought Germany’s Jewish populations into contact with a new type of anti-Semitism developed as one method of control in the Assad dictatorship.

The uncritically anti-Israel and anti-Semitic tropes that have been taught, promoted, or tolerated in Syria pose a new set of challenges to German authorities who are still wrestling with their country’s past. Germany, because of its history, has accepted upon itself a greater responsibility than other European countries to take in refugees. Now it must take on another major responsibility: effectively educating these communities about the Holocaust and the insidious nature of anti-Semitism.

I am particularly conscious of this issue as a Syrian who now calls Germany home. Before the start of the Syrian civil war, I traveled to Europe with the intention of learning the skills I would need to open a wine bar in the old city of Damascus. But my sojourn to the German countryside opened my eyes to much more than the intricacies of the wine industry. There, I confronted the root of my own prejudices towards Jews while in the process coming to a realization about the role anti-Semitism plays in own country’s deception of its people.

Back home in Syria, what started as a peaceful uprising in 2011 swiftly ignited into a full-fledged civil war, consuming an entire nation along with its neighbors. While the conflict has raged for over nine years, the Syrian dictatorship has managed to cling to power. The international community was collectively unable to intervene in this human catastrophe, contributing to the largest refugee crisis since the Second World War.

Many of these refugees fled from Syria—one of the most anti-Semitic countries on earth—to Germany, which is still repairing its complex and fraught relationship with the Jewish people. Now, Germany must recognize and seek to understand the embedded nature of anti-Semitism in Syria in order to better help its newest residents to live lives free of state-sponsored prejudice.

The Reach of Anti-Semitism Inside Syria

For decades, the Syrian Ba’athist regime systematically incited hatred and anti-Semitic propaganda against the Jewish people. The influence of anti-Semitism is perhaps most overtly visible in Syria’s foreign policy; the Ba’athist regime has unapologetically supported terrorist organizations that target Israeli civilians, such as Hamas and Hezbollah. The Regime’s backing of these organizations should not be miscategorized as support for the Palestinian cause—the horrific state of the Palestinian refugee camp of Yarmouk in the southern outskirts of Damascus shows the Syrian regime’s blatant disregard for Palestinian lives. Rather, support for these terrorist organizations should be seen as some combination of political expediency and its real hatred of Jews.

Emblematic of this trend is the Syrian Regime’s decision to take in Abu Daoud—one of the architects of the Munich Olympic attack—in 1993, making it the only country to agree to do so and thereby allowing this terrorist to evade international law up until his death from natural causes in 2010. Decades earlier, the Syrian government also made the decision to harbor the Nazi fugitive Alois Brunner, who was responsible for the death of at least 128,000 Jews. Alois Brunner is also reported to have become instrumental in establishing the Syrian Intelligence Service—the feared Mukhabarat—which has been responsible for mass deaths and murders of Syrians.

However, anti-Semitism is also endemic inside of Syria, and has taken root at every level of society. Religious leaders quote—out of historical and religious context—Quranic scriptures to drive this ideology of hate, while many Syrian intellectuals and artists adopt the hateful rhetoric of this dictatorship without question.

Syrian popular literature is one area that demonstrates the deep relationship between the Syrian state, state-mandated culture, and anti-Semitism. In 1983, then Minister of Defense Mustafa Tlass published a book titled The Matzo of Zion that described ‘The Damascus Affair,’ a historical incident where thirteen Damascus Jews were arrested on accusations of ‘ritual murders’ in 1840. This book, presenting unfounded accusations as fact, repeats the ancient “Blood libel” myth that Jews murder non-Jews to use their blood for religious rituals. Tlass was an adamant anti-Semite, confident that all Jews––not just Israelis––are bloodthirsty by nature. He asserted that Judaism is a “‘vicious deviation,” and that Jews possess “black hatred against all humankind and religions.”

The anti-Semitic propaganda in The Matzo of Zion mirrors the language of both Mein Kampf and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The Matzo of Zion reached similar levels of popularity in international anti-Semitic circles, but is perhaps most easily purchased in Damascus, where it is effectively sold on almost every street corner for the affordable price of $2. In fact, none of the aforementioned anti-Semitic literature appear on the lengthy list of banned works in Syria, which allows these works’ uncritical dissemination.

But perhaps the best and most influential example of anti-Semtism in Syria since the start of Bashar al-Assad’s rule is the twenty-nine-part Syrian television series Ash-shatat—‘the Diaspora.’ The writer, along with some of the Syria’s most prominent actors, have delivered an appalling compilation of anti-Semitic canards and libels, presenting Jews as the most wicked and immoral people on earth. Ash-shatat is not the only Syrian or Egyptian television production to spread anti-Semitism, but it is the most influential. The television series achieved a regional audience, airing in Iran in 2004 and in Jordan in 2005.

A Potential Solution: Education and Awareness

Despite these examples of deeply rooted anti-Semitism in Syria, it is possible to reverse such an intensive indoctrination: after all, German public discourse is a living example. My own visit to the memorial site at Dachau opened my eyes to the horrific extent of cruelty and human suffering experienced by the individuals in this camp. Though absent from Syrian collective consciousness, sites like these unequivocally assert that the Holocaust occurred. At Dachau, comforted by Jewish companions, I wept not only from grief but from shame—the shame of growing up in a culture that denies the Holocaust, or at best asserts that it was a Zionist decision to ‘sacrifice’ Jews in order to promote immigration to Israel.

Now more than ever, Germany has its own domestic challenges again rising to the surface: the far-right ideology that has resurfaced throughout Europe in apparent response to the refugee crisis has provoked a resurgence of both anti-Semitism and Islamophobia—particularly in Germany. On the one hand, many fear that if Germany fails to address its current situation, the world could relive one of its darkest moments in history. German Jews have already been told by Jewish leadership to refrain from wearing Kippahs in public and remove mezuzot from their doors—many have begun to conceal their identity. The attempted attack on the Halle Synagogue—though prevented from becoming a full-blown massacre by a locked door—still led to a loss of life and demonstrates the repercussions of not actively addressing this issue. On the other hand, if this issue is prioritized, as was publicly called for by Germany’s foreign minister, Germany will have the chance to confirm its position as a ‘land of opportunity,’ where people from around the world can reinvent themselves.

Yet while the German government has vowed to combat anti-Semitism, its threats so far have mainly consisted of unspecified consequences for individuals who attack German Jews. As a Syrian, I know that warnings alone are not enough to counter decades of anti-Semitic messaging. In febrile minds of extreme anti-Semites, attacking Jews can be seen as an honorable and courageous act. In many cases, these individuals have been conditioned since birth to perceive the Jewish people as their enemy, themselves victims of a narrative designed to prevent them from holding their country’s dictators accountable for the widespread misery felt throughout the Arab world.

Syrians must educate themselves on persistent history of anti-Semitism, which did not start with the Holocaust—nor end with the creation of the state of Israel. Every Syrian who aspires to become a European citizen must refuse to be an anti-Semitic extension of their government. Germany with its years of retraining its own population has a lot to offer on this front, but the German government must make this a priority and a commitment with its deeds as well as its words.

A Europe unsafe for Jews will never be safe for other minorities. When Syrian communities throughout Europe come to recognize this reality, there is the remarkable potential for fostering a conducive environment for Jews and Syrians to respect one another, encouraging understanding and cooperation between neighbors and mutual support of minority communities throughout Europe. However, getting to this point will require a lot of effort and determination, both on the side of the German government and among Syrian communities themselves.