- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

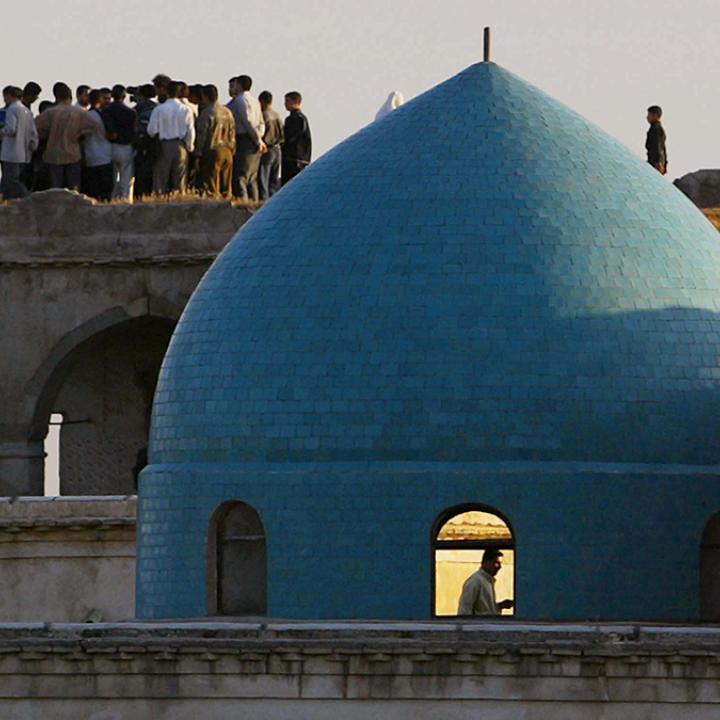

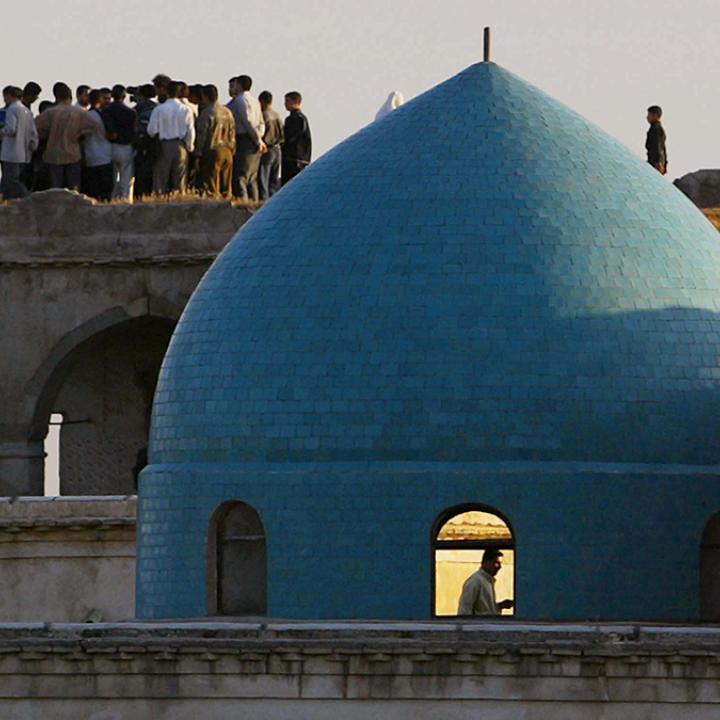

After Arson in Kirkuk Against Kurdish Farmers, Kurdish Parties Remain Divided

With the tensions between Washington and Tehran, a potentially dangerous conflict in Iraq—ethnic tensions are simmering between Kurds and Arabs in the country’s disputed territories, especially in the multiethnic province of Kirkuk. In the past few weeks, reports from Kurdish news sources allegedly indicate that Arab actors have set hundreds of acres of Kurdish wheat and barley crops on fire in an attempt to drive Kurds out of their lands, though whether these actors are affiliated with ISIS or Iraq’s paramilitary forces remains unclear. Meanwhile, Kirkuk’s local government remains unresponsive while the two main Kurdish parties—the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP)—are squabbling over petty partisan politics, further complicating the situation for Kurds in Kirkuk.

Background of the Conflict

On October 2017, Kurds lost control over the disputed areas of Kirkuk after the Iraqi army, backed by Shiite militias, attacked Peshmerga forces in the region when the Kurdish Regional Government’s attempted referendum for independence included Kirkuk. The attack triggered a messy, abrupt withdrawal of Peshmerga from Kirkuk, Ninewa, and Diyala provinces, with consequential implications for the regions’ Kurds.

For the first time since 2003, Kurds lost military, security, and political clout over areas that, while disputed, are historically claimed by Kurds as an inseparable part of the ancestral homeland of Kurdistan. From a military angle, Kurds lost control over key security and military institutions based in the areas. Economically, Kurds lost control over the Kirkuk oil fields, which had served as a lifeline for the Kurdish government. On the demographic front, an estimated 100,0000 Kurds, fearing retribution from the Iraqi army and unfettered militia groups, left the area and became IDPs in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Politically, the elected governor of Kirkuk, Najmaldin Karim, was removed and replaced by an acting governor, Rakak al-Jibouri. The new governor’s aggressive policies to replace key Kurdish members of local political, economic, security, and educational institutions with Arabs has contributed to the dozens of violations recorded against Kurds in the past several years.

In part as a result of al-Jibouri’s policies, many Kurds in Kirkuk feel that the balance of power has titled towards the minority of Arabs living there. Of particular concern for the region’s Kurds are reported attempts by Arabs to reclaim Kurdish lands that had been given to Arabs by the former Iraqi regime as part of a process of Arabizing Kurdish regions in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, in some cases using illegal measures to do so. In most cases, these Arabs—referred to as “brought-in Arabs” due to the fact that they were brought in from other areas of Iraq to occupy Kurdish and Turkmen lands during this period—had been moved off these lands and compensated financially after the fall of Saddam under Article 140 of the 2005 Iraqi constitution. However, some still feel entitled to these lands, which have been reoccupied by Kurds over the past decade.

It is also these contested lands that have been torched over the past few weeks. On May 14, armed with AK-47s and other light weapons, sources reported that some two hundred of the ‘brought-in’ Arabs marched into the Kurdish village of Palakana in Kirkuk province, raiding the village, attacking residents, and threatening to wipe out the village if the Kurds would not leave. This attack does not appear to have been extemporaneous; rather, it may have been encouraged by an earlier decision issued by the Salahadin Military Operation Command to prevent Kurds from harvesting their crops.

The military order raises the question of under what jurisdiction and authority a military commander could make such consequential decision without consultation with the central civilian authority in Baghdad. This action by the Operation Command is likely to reinforce the understanding that Iraq suffers from far worse decentralization and multiple centers of power than previously thought, which bodes poorly for Kirkuk.

In an ideal world, a country’s army is expected to act as an honest, neutral broker for all segments of society. The neutrality of the Iraqi army is enshrined in the country’s constitution, yet this ideal battles an established norm from an earlier era of viewing Iraqi Kurds as “the other.” Ultimately, the constitutional article does not appear to have succeeded in altering the thinking of Iraq’s military establishment in Iraq towards Kurds. According to the accounts of Palkana residents, while the army did come to the village during the attack, military units reportedly stood alongside those who were attacking the Kurds. Several villagers also claimed that Iraqi army humvees pointed their machine guns at local Kurds in the village.

In a press conference, Kirkuk’s Acting Governor Rakan al-Jabouri expressed support for the attacks on Palkana and other Kurdish villages. Jabouri claimed that the administrative procedures in Palkana village were legal actions and alleged that some of the residents were Iranian Kurds from Mahabad in Iran without offering any evidence to back up his claims.

Due in part to this unsubstantiated and irresponsible claim by the regional governor and the failure of the Iraqi army to curb the vandalism of Kurdish farm lands, attacks on Kurdish crops have increased since this initial attack and have spread to the province of Diyala as well. On May 16, 400 acres of Kurdish farm lands were reportedly set on fire on in the villages of Mubarak, Dara, and Mekhnas in Khanaqin area. On May 19, backed by the Iraqi army, some 25 Arabs reportedly stormed the village of Sargran in Kirkuk, preventing Kurds from harvesting their crops. Just a day earlier, in the evening of May 18, two alleged ISIS motorcyclists set fire to crops in two villages near Sargran.

In Sargaran, Local Council member Badradin Shamsadin claimed that the Arab attackers had a list of seventeen villages to target in the region, including Palkana, Sarbashakh, Shanagha, Darband, Jastan, Talhalala, Jastuma, Chard, Gabalaka, Kharaba, Qoch, Qaplan, Saralu, Lheban, Sargaran, Dawdgruga, and Sequchan. According to Shamsadin, Kurds were forced to halt harvesting their crops in these villages.

In addition, According to Kirkuk Agriculture Directorate head Mahdi Mubarak, the burning of Kirkuk farmland took take place under the watch and by support of Iraqi forces and Kirkuk’s acting governor. Mubarak added that 12,000 Arab families had been brought to Kirkuk since 2017 and argued that the city was witnessing a deliberate process of Arabization and social engineering through the settling of Shiite Iraqis in Kirkuk.

The measures taken by the Iraqi army during this period are particularly troublesome in two respects. First, inaction further reinforces the notion among the area’s Kurdish inhabitants that the Iraqi army has not changed from the repressive army that committed a variety of gross crimes against Kurds, including acts of genocide, in prior decades. Secondly and even more dangerously, if the Iraqi army is perceived of as backing one ethnic group against the other—and indeed if the army does in fact do so—this partisanship could deepen ethnic conflict in contested areas of Iraq and embolden radical actors to continue acts of violence. This tension could eventually lead to an ethnic conflict, a fate that Kirkuk has thus far avoided despite all odds.

Further complicating the matter is the fact that local authorities have attributed many of the attacks on Kurdish farmland to ISIS. Yet given the chronology of the events and eyewitness reports, many Kurds in Kirkuk believe that ISIS may be being used as a scapegoat for crop attacks. Even if individual attackers were ISIS members, the injudicious actions by the Iraqi army and the Kirkuk governor that have paved the way for people to take such bold measures under the name of ISIS cannot be discounted as contributing to the targeting of Kurdish farmers.

Moreover, the circumstances of some attacks that have been reported also suggest that ISIS forces are not the only military groups involved. Another incident occurred on May 21 in the Qaretagh village of Qaratapa near Khanaqin, and on the evening of May 22, crops were set on fire in two villages in Daquq under unknown circumstances, targeting an area populated by the Kakei Kurdish minority. Salah Baban, a member of town council, said in an interview that it was not clear who had set the farms on fire, but he pointed out that the fields had been near a base of Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), Iraq’s paramilitary forces. Such accusations against the PMF were also made by Sheikh Jafar Sheikh Mustafa, the chief of the Kurdistan Democratic Party's 15th Branch in Khanaqin, who said he believed that the PMF, rather than ISIS, was behind the fire. According to Mustafa, 700 acres of Kurdish farmlands has been intentionally burned, including 150 acres in Jalawla alone.

According to these figures, more than a thousand acres of Kurdish farmlands in total have been set on fire in Kirkuk and Diyala provinces, which is currently under the protection of the Iraqi army and the Shiite militia groups of the PMF. And as of yet, no one has been held accountable for this vandalism. And as a result, the arson attacks have created an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty for Kirkuk’s Kurds, who feel as though they now lack political or military protection from their local and the federal governments.

The Failure of a Kurdish Political Response

To calm down the situation, Kurdish political parties, officials, and MPs in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region and Iraq have issued several letters of protest against the oppression of Kurds in these disputed areas. However, the two main Kurdish parties—the KDP and PUK—have failed to coordinate their efforts to counter the targeting of Kurds within the Kirkuk region.

Instead, the two parties are busy blaming each other: the KDP continues to claim that the PUK is responsible for the 2017 loss of Kirkuk and its aftermath without offering realistic approaches or solutions to the issue, while the PUK—with a full six of twelve parliamentary seats in Kirkuk—is busy working with Arab and Turkmen politicians in Kirkuk at the expense of the KDP. In other words, infighting between the KDP and the PUK on Kirkuk has taken a toll on the region’s Kurds who continue to be displaced and suffer from political and security uncertainties.

Kurds control 26 out of 41 members of the Kirkuk provincial council (KPC) but the friction between the KDP and the PUK has prevented the council from convening in order to appoint a new governor for Kirkuk. The PUK has tried to convene the KPC several to appoint a governor, but due to the lack of quorum because of a boycott by KDP members, this has thwarted the PUK’s efforts to unilaterally decide on the governorship. At issue are the KDP’s demands for an independent figure to occupy the post, while the PUK wants its own choice for governor.

It’s not clear whether Kurdish officials, including the Iraqi President Barham Saleh in Baghdad, would be able to stop violence, Acting Governor Jabouri’s apparent efforts to Arabize the disputed areas, or the removal of Kurds from political and security protections. Yet individual politicians are speaking out against the current political inaction: Politburo Executive Chief Mala Bakhtiar warned that if the Kurdish officials in Baghdad did not take a position regarding what many Kurds perceive as an Arabization process in Kirkuk, they would not be any different than the Kurdish politician Taha Muhieldin Maruf, who was Saddam Hussein’s Vice President throughout much of his most repressive acts against Iraq’s Kurds.

However, the real solution for Kirkuk should come from the Kurdistan Region’s political parties. Were the KDP and the PUK to work together to reach a deal to appoint a new governor in Kirkuk who supports the region’s interests as a whole, Kirkuk’s Kurds could restore their confidence in the local government. However, working to reverse actions taken since 2017 to weaken Kurdish position in the province on the political, economic, military and social fronts required the KDP and the PUK to work as a united front, a position that the two parties are not willing, as of yet, to take.

.find_in_page{background-color:#ffff00 !important;padding:0px;margin:0px;overflow:visible !important;}.findysel{background-color:#ff9632 !important;padding:0px;margin:0px;overflow:visible !important;}