- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Erdogan Unlikely to Back Down in Mediterranean Despite Oil and Gas Glut

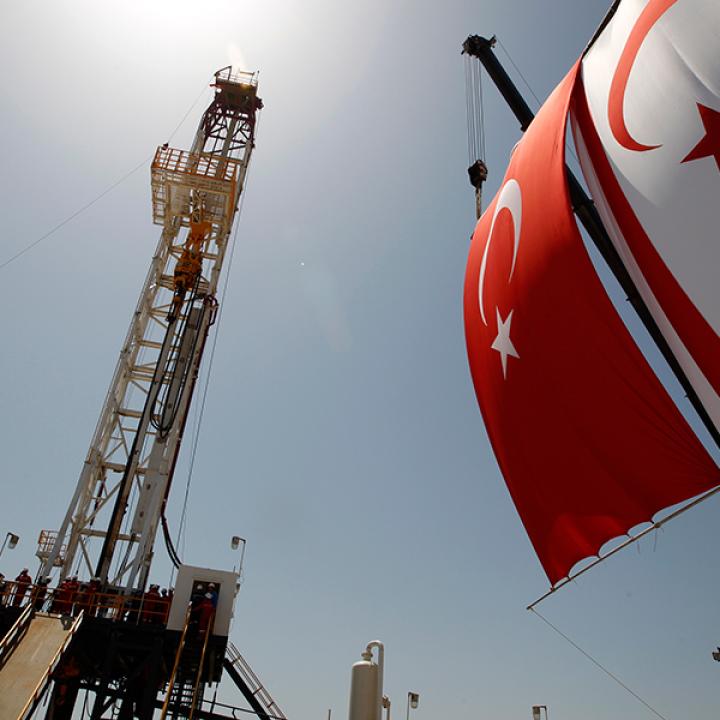

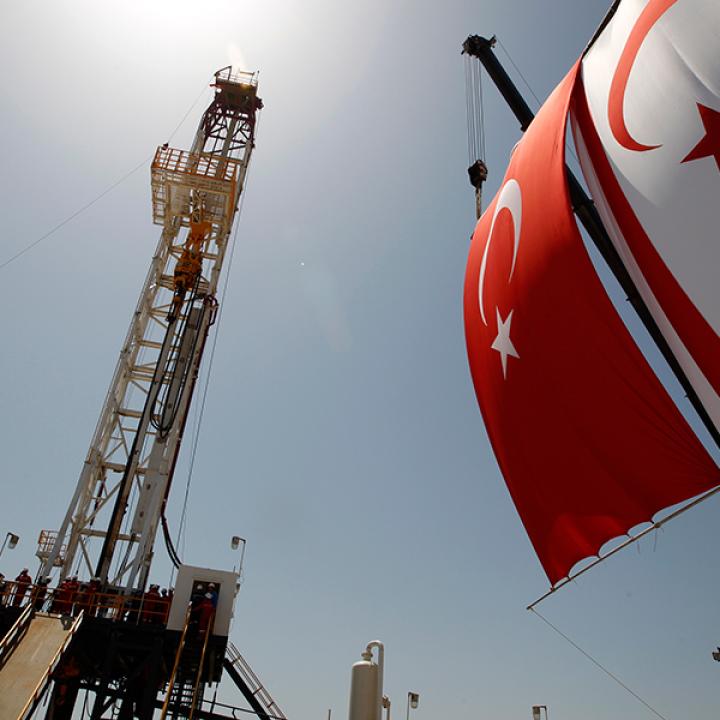

The low price of oil and gas has not deterred Ankara from continuing to explore disputed waters around the divided island of Cyprus. The Turkish government’s upstream offensive—a combined effort of the state-owned Turkish Petroleum (TPAO) and the Turkish navy—in the East Mediterranean is clearly being driven by its Blue Homeland doctrine, which focuses on aggressively defending Turkey’s offshore sovereign rights. The configuration of domestic politics combined with regional successes has bolstered the importance and viability of this doctrine, with little in the way of pushback from other involved parties.

These actions will likely have major repercussions on the future of the maritime oil and gas industry in the East Mediterranean. Turkey is through its own exploration looking to frustrate the energy ambitions of rival littoral states and their associated oil and gas business partners centered on the contested water around the island of Cyprus. At present, international oil companies (IOCs) partnered with Greek Cyprus do not face an immediate threat of disruption to their offshore operations by the Turkish navy; Eni, Total, and ExxonMobil have postponed drilling and seismic activities until 2021 due largely to current suboptimal oil and gas prices. But given President Erdogan’s steadfast commitment to the Blue Homeland doctrine and his determination to maintain power in Turkey’s next election, the geopolitical outlook for the East Mediterranean is unlikely to improve when these companies look to resume operations next year.

Working for the Turkish Nationalist Vote

President Erdogan’s electoral calculations go a long way in explaining the current push by state-owned Turkish Petroleum (TPAO) to drill in waters claimed by Turkey and its junior partner, Turkish Cyprus. These drilling sites controversially sit in the internationally recognized Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Greek Cyprus, an EU member.

Having antagonized the bulk of Turkey’s Kurds and liberals, and having eroded the support of his long-standing pious base, Erdogan has increasingly come to rely on naked nationalism to sustain his rule. Turkey’s power projection in the East Mediterranean caters directly to the country’s large pool of nationalist constituents. The efforts also underpin Erdogan’s vision of Turkey as a fiercely independent and formidable regional power.

Given these motivations, there is a high risk that Erdogan will intensify tensions in the East Mediterranean over the next several years. Doing so would help the president boost his appeal for ultra-nationalist coalition partners and their supporters in upcoming national elections. With Erdogan’s party faring poorly during last year’s local elections—including a significant loss in Istanbul—Erdogan’s national position looks fragile. Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections are currently scheduled for 2023, but many local observers believe Erdogan could call snap elections in 2021 or 2022 in an attempt to catch the political opposition off guard.

The Blue Homeland doctrine pursued by Erdogan’s government is designed to appeal in particular to Turkey’s ultra-nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), already allied with Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). Confirming and solidifying this alliance will leave Erdogan more confident that he can rely on MHP votes in the presidential polls, which were a significant help in the 2018 national elections.

Map showing waters claimed by Turkey and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Source: ©Verisk Maplecroft, 2020; Flanders Marine Institute, 2018; status of control information derived from a number of mapped sources

Turkey Emboldened by Libya and Weak EU Response

The fact that Ankara has not been subjected to biting sanctions for drilling in the waters of an EU member state can also help explain Ankara’s interest in further adventurism. Turkey has only received a slap on the wrist for drilling in Greek Cypriot waters—including a $163 million cut in pre-accession funds and targeted sanctions against two senior TPAO executives.

Erdogan knows that the EU is unlikely to develop the stomach for a full-blown political showdown with Ankara anytime soon. The Turkish government feels it has significant leverage against the EU; apart from its ability to exacerbate tensions in Europe’s southern flank, the president could once again bus thousands of Syrian and other migrants directly to the EU’s doorstep. European politicians’ fear of another migration crisis—especially in the midst of an economic contraction and the continued repercussions of the COVID19 pandemic—has put Erdogan in a particularly favorable position regarding any potential conflict with the EU.

These dynamics have recently played out in Libya, where Erdogan has achieved what is arguably his biggest strategic and foreign policy coup in recent years. Ankara’s expanded strategic and security ties with the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) have led to an MoU delineating the territorial water boundaries between Turkey and Libya. Through this MoU, Ankara is effectively annexing part of Greece’s continental shelf. Much to the ire of Athens, TPAO is now preparing to commence exploration in acreage that sits within Greece’s EEZ in three to four months.

To make matters worse for Greece, the Turkish navy, which has enhanced its presence in the East Mediterranean as a demonstration of Turkey’s interests, has been emboldened by its recent successes. In June, a Turkish warship prevented a Greek naval ship deployed under Irini—the EU’s naval mission to enforce an arms embargo on Libya—from inspecting a vessel destined for Libya. Again, the EU has failed to respond to this incident in an effectively deterrent manner.

The MoU between Ankara and the GNA has also added further uncertainty to plans by Greece, Greek Cyprus, and Israel to construct an East Mediterranean gas pipeline across its sea bed. Though this project has been commercially unconvincing since its inception, Turkey has stated it will block construction in waters it controls.

European politicians know that they are unlikely to be able to convince the GNA to ditch its strategic relationship with Ankara, to which it is heavily indebted. Turkey’s provision of Syrian mercenaries, drones, military trainers, and naval support to the GNA was pivotal in preventing the Libyan National Army (LNA) from seizing control of Tripoli and forcing it into retreat. As such, Ankara is in an excellent position to move forward on its own oil and gas interests in the East Mediterranean.

Peace Deal on Cyprus Possible but Unlikely

The one rather unlikely scenario with the potential to moderate Turkey’s aggressive drive in the East Mediterranean would involve the relaunch of peace talks to settle the disputed status of Cyprus. One of the reasons Ankara has looked to disrupt Greek Cypriot-mandated offshore exploration is to force Greek Cyprus to provide iron-clad guarantees that Turkish Cypriots will fully benefit from hydrocarbon revenues from offshore production before a peace deal is implemented.

The impasse also comes from Ankara's refusal to remove its estimated 35,000 troops from Turkish Cyprus before a deal is implemented, as demanded by Greek Cyprus. As such, achieving a breakthrough on Cyprus would require compromises on all sides—flying against Erdogan’s domestic political agenda running up to the elections.

The geopolitical outlook for the East Mediterranean is therefore likely to remain negative. The combination of Turkey’s ongoing drive to drill in disputed waters, the increased presence of a Turkish navy ready to intercept IOC drilling vessels, and the inability or ineffectiveness of the EU to contain Turkey all factor into the likely trajectory of this conflict.

At the same time, it is not inevitable that Turkey will disrupt IOC operations in the East Mediterranean in future years. The threat of the Turkish navy harassing IOC drilling vessels will be at least partially offset by the continuously strong presence of the French navy in the East Mediterranean. Eni is especially fortunate to be partnered with France’s Total, whose assets are a primary concern for the French fleet. It also helps that ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum’s block 10 does not sit in waters claimed by Turkey or Turkish Cyprus.

IOCs are likely to indefinitely postpone or abandon drilling plans in the East Mediterranean should the oversupply of natural gas persist over the coming years. This would reduce Turkey’s ability to pressure rival littoral states in the East Mediterranean, but we would still expect Ankara to continue flexing its muscles in contested waters. So long as Turkey continues hosting millions of migrants and enjoys strong influence in Libya—Europe’s soft underbelly—the ability of European politicians to force a partial rethink in Turkish policy will be limited.