- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

The Future of Kurdistan, Between Unity and Balkanization

The Kurdistan Region is often praised as an anchor of stability in the Middle East; its military forces in particular are considered a major bulwark against the Islamic State (ISIS). Nonetheless, it faces potential balkanization as provincial voices begin advocating for autonomy from the Kurdish core. Both political parties and local officials are searching for more power and wealth, further dampening the prospect of an independent Kurdistan.

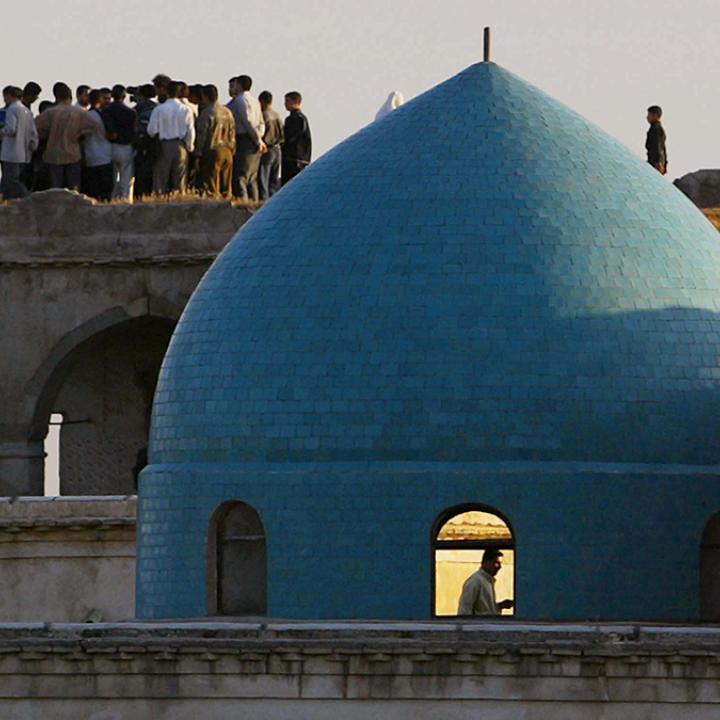

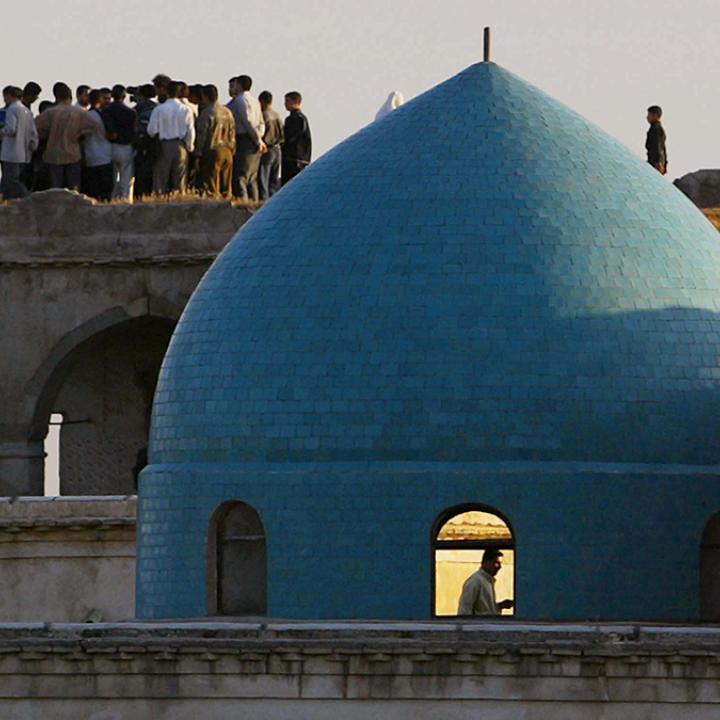

In an interview with the Kurdish newspaper Rudaw, Kirkuk governor Najmaldin Karim voiced support for the formation of an autonomous Kirkuk Region. Karim justified his stance due to Baghdad’s unfair treatment of the province regarding financial payments, security, employments, and alleged attempts of increasing the flow of Arab refugees to force demographic change in the province. While Kirkuk is not officially under the control of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the KRG Peshmerga forces have exerted de-facto control over most of the province since the breakdown of the Iraqi army in the face of ISIS’s onslaught in 2014.

A separate Kirkuk region seems to be an acceptable compromise for the multiethnic province that has been the center of constant conflict between Baghdad and Kurds for the last century. However, the governor has faced backlash for his suggestion on various fronts: the rival Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) has vowed to do everything to stop the governor’s agenda as it seeks to hold a non binding referendum about the future of Kurdistan Region. Meanwhile, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)—the governor’s own party—has categorically rejected the notion of an autonomous Kirkuk Region. Some PUK officials have called the idea a “Turkish project” meant to counterbalance Kurdish hegemony in Iraq and control the province’s oil.

Nevertheless, the idea of an autonomous region is not new. It was first proposed by the Turkman Front in Kirkuk in 2007, when, according to the Iraqi constitution, a referendum should have been held by December of 2007 to decide whether the province would join the Kurdistan Region or remain within a federal Iraq. However, both Kurds and Arabs rejected this initial proposal. In 2008, former Iraqi president Jalal Talabani reinvigorated the notion of an autonomous Kirkuk Region, again stirring up controversy.

But Talabani and Karim’s may face legal and constitutional resistance along with political challenges. The Iraqi constitution does not allow for two autonomous regions to join into one, which has led some Kurdish officials to argue that a separate Kirkuk Region would indicate the demise of any hope that the oil-rich province would one day join the Kurdistan Region. Arif Qurbani, a PUK official, claims that the danger of separating Kirkuk is not its separation from Baghdad but in the separation of the province from Kurdistan. The KDP rejects such a notion outright, labeling it “treason” and “unacceptable.” Moreover, in a recent statement the U.S. State Department voiced its support for a united government over an autonomous Kirkuk Region.

Despite the widespread condemnation, Kirkuk’s governor is not the only local official attempting to rebel against the KRG; frustrated officials from the province of Sulaymaniyah also seek to declare a “decentralized governance” to allow the local administration to control to its own finances and funding. The Sulaymaniyah provincial council gave a two week deadline to the KRG to respond to province’s demands. Sulaymaniyah’s provincial council chief, Haval Abu Bakir, told the Slemani News Network that if his people’s demands remained unfulfilled, they will take other measures, such as meeting with political parties and media campaigns. If these measures also fail , local governance would implement decentralization for the province and make executive decisions themselves.

Sinjar, mostly populated by the Yezidis, is another area that seeks autonomy from the KRG. Kurdish parties also oppose this move, especially KDP officials, who control the area jointly with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The Yezidis’ calls arose after ISIS took over Sinjar in August of 2014 and Kurdish forces failed to protect the town, resulting in a massacre of thousands of Yezidis and the enslavement of hundreds more. Under the auspices of the PKK, some people from Sinjar declared autonomy, but the KRG has condemned the action, calling it “illegal and contrary to the law and constitution of Kurdistan and Iraq.

Whether Sinjar, Sulaymaniyah, or Kirkuk will go ahead with decentralization or not remains to be seen. Nevertheless, such calls are troubling symptoms of the divide within Kurdistan’s inhabitants, who continue to suffer from a lack of basic services, institutional corruption, a lack of transparency regarding oil and gas, and a continued political stalemate between the Kurdish political parties.

In the meantime, frustrated by the KDP’s refusal to share power or reactivate the Kurdistan parliament paralyzed since last year, the PUK and the Gorran Movement recently signed a new treaty. Some analysts believe that this rapprochement was intended to force the KDP to comprise over power and wealth sharing.

Efforts to form separate autonomies within the Kurdistan Region could further polarize Kurds over the partisan lines, which will eventually scrap the potential of an independent Kurdistan, regardless of some favorable national and international circumstances.

Yerevan Saeed is a Ph.D. student at the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution (S-CAR), George Mason. He previously served as White House Correspondent For Kurdish Rudaw TV, and has worked for news agencies including the New York Times, NPR, the Wall Street Journal, the Boston Globe, the BBC and the Guardian as a journalist and translator. This article was originally published on the Fikra website.

Fikra Forum