- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Migrants Likely to Remain Pawns in Turkey-EU Relations for Years to Come

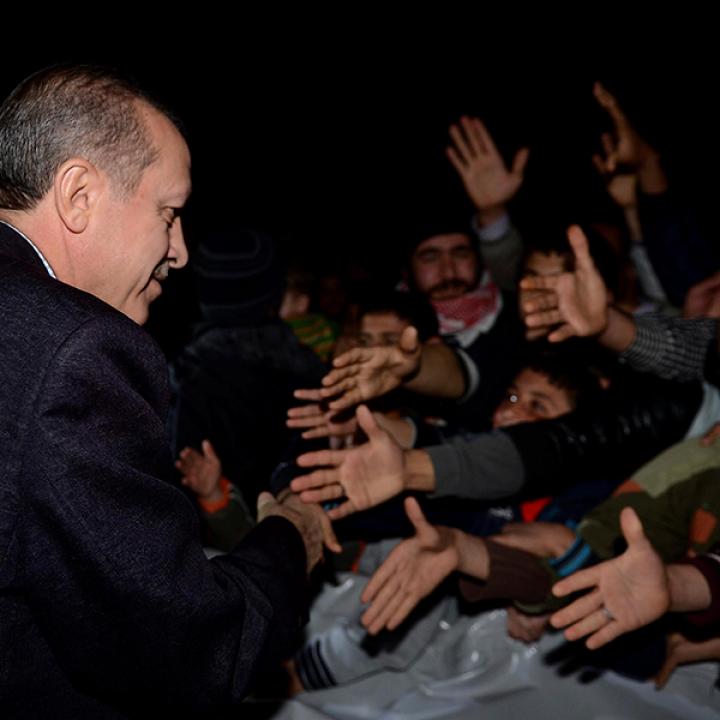

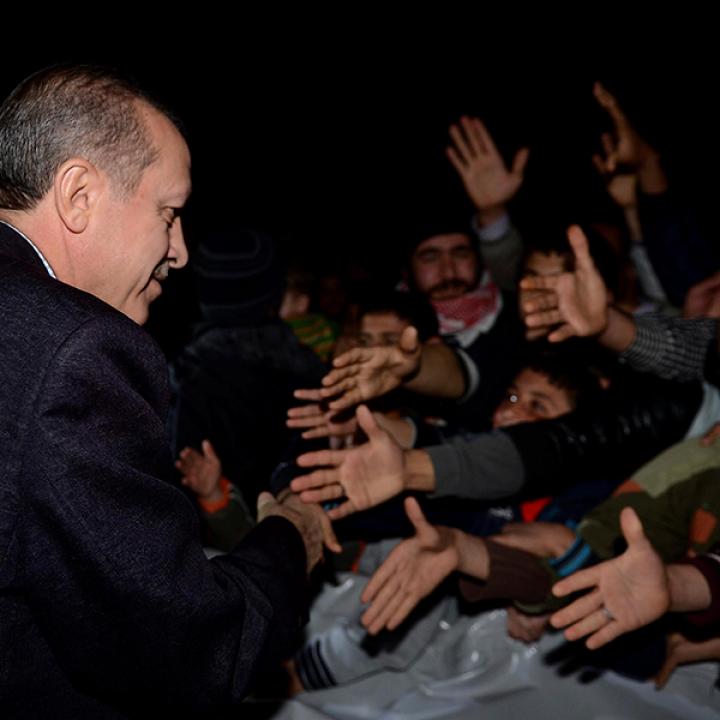

With the spread of coronavirus restricting travel, European leaders are meeting virtually with Ankara this week in an attempt to resuscitate and potentially fine-tune a flawed migration deal from 2016, which has now effectively collapsed. This will come as the second attempt in less than a month to reach an agreement, with President Erdogan’s visit to Brussels on 9 March coming to naught. In February, Turkish officials announced their decision to stop preventing refugees from fleeing across the Turkish border into Greece and Bulgaria after years of repeated threats from Erdogan to reopen the Turkish borders in responses to unfavorable EU policies. This sparked tense interactions between refugees and Greek and Bulgarian authorities who continue to patrol their sides of the border.

The EU’s current objective is to prevent President Erdogan from encouraging millions of Syrian and other migrants to attempt the crossing into Europe from Turkey and to extract guarantees that Ankara will not use migrants as political pawns in the future. Erdogan decided to ditch the migrant deal after fellow NATO member states turned down Turkey’s calls for the establishment of a no-fly zone in northwestern Syria to stop Syrian President Bashar al-Assad from targeting Turkish military forces and displacing hundreds of thousands of Syrians who have moved towards the Turkish border.

However, even if the two sides do manage to strike a deal, such an agreement would be no more likely to stick than the earlier agreement in 2016. Erdogan is likely to once again use the threat of an influx of migrants into Europe and the suffering they endure at the hands of Europe’s border security guards to pressure European politicians on a range of issues over the coming years.

Erdogan knows all too well how important efforts by the Turkish coastguard and land-based security forces have been in deterring Syrian and other migrants from reaching the border with Bulgaria and Greece. As the chart below demonstrates, the 2016 deal greatly reduced the influx of migrants into Europe. The drop in migrant arrivals in 2015 before Turkey and the EU signed the migration deal derived from the anticipation and onset of autumn followed by winter, when conditions in the Mediterranean are far tougher.

During peak periods of tensions between Turkey and the European Union, the Turkish government will consider whether to once again help migrants move towards the Greek and Bulgarian borders.

* Figure: Number of migrants by year entering Europe

EU to Blame for Failure of Migration Deal

The reluctance of European leaders to meet President Erdogan’s expectations explains partly, though not wholly, why there should not be an expectation that an amended migrant deal will stand the test of time. Erdogan’s expectations are enshrined in the portions of the 2016 agreement that remain unimplemented; which include, visa-free travel for Turkish passport holders entering the EU, a commitment to opening new chapters in Turkey’s stalled EU accession bid and intensified bilateral efforts to expand the EU-Turkey customs union. The EU also committed to disbursing an initial sum of €3 billion under the Facility for Refugees in Turkey, followed by another injection of €3 billion by the end of 2018. While the EU has allocated almost all of the promised €6 billion for Syrian migrants in Turkey, merely €3.2 billion has been spent so far on health centers, schools, and the like. Erdogan says the funding is inadequate to help ease Turkey’s heavy migrant burden.

European leaders put these appealing incentives on the table in 2016 to get Erdogan to play ball, but the likelihood that they would ever be implemented was already slim. The Turkish government may have failed to meet benchmarks, harmonize policies, and improve its human rights record in the ways required to trigger the implementation of these benefits, but the Europeans should have recognized that promising such incentives was placing unrealistic expectations on Turkish governance. Such an unrealistic outcome should never have been placed on the table to begin with. Moreover, the lack of trust between Turkey and the EU undermines the likelihood of a new deal lasting, even if its parameters are substantially narrowed and at least initially agreed.

Just as Turkey stands no chance of joining the EU under Erdogan, European politicians are unlikely to grant visa-free travel for Turkish passport-holders in the Schengen zone over the coming years. Granting visa-free travel to Turkish nationals would be milked by anti-establishment, right-wing parties and figures in Europe, while potentially stoking EU scepticism and Islamophobia. The Schengen Zone is in any case currently being internally compromised as borders close to contain COVID-19–demonstrating the limits of the EU’s ‘open borders.’

Irrespective of the EU’s justification for not sticking to the original roadmap, Erdogan will continue to point to a stark reality; namely, that European politicians are exhibiting double standards on human rights by criticizing his administration for repressive rule while not pitching in sufficiently to support migrants from war-torn states. Turkey’s commitment to supporting the 3.6 million Syrian migrants it already hosts by far outstrips the support provided by the EU as a whole. After several years of this arrangement, it is unsurprising that Erdogan is demanding that Europe shoulder a bigger burden.

Migration to remain a trump card for Erdogan in Mediterranean

For Erdogan at least, a renegotiated deal is not even necessarily more advantageous than the status quo; being at odds with Europe over migration policy is in some ways diplomatically advantageous for Erdogan. These advantages are clearly evident in the ongoing tensions over Turkey’s current forays into drilling in contested waters in the East Mediterranean. One of the main reasons why EU member states have not slapped Turkey with heavy penalties for their drilling is the threat of Erdogan keeping the migrant floodgates open on Europe’s southern borders for weeks or months.

The migrant issue is also likely to have factored into Europe’s limited material response to the Turkish government’s November 2019 announcement that it has signed an MoU on territorial water delineation with the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA). The EU has not imposed biting penalties despite the deal directly impinging on Greek waters as defined by the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea, though Turkey is not a signatory state.

So regardless of what is or is not decided this week, Erdogan is likely to continue leveraging Turkey’s status as the world biggest host of registered refugees in an effort to extract more concessions from the EU as he looks to achieve his foreign policy objectives in the East Mediterranean and further afield. The president knows that negative optics of migrants being beaten back on Europe’s southern frontiers will continue to pose a PR problem for Europe’s politicians for years to come, and the EU should expect that he will continue to exploit this reality to the fullest.