Surviving the Transition in the Middle East

Presently, almost all global and regional actors insist on protecting the current borders; however, they offer no vision on how to protect the people and law and order inside them. In a volatile region where co-existence between communities is becoming increasingly difficult, imposing borders on them will remain an even greater challenge.

January 24, 2017

A bird’s eye view of the Middle East landscape shows a region now riddled with conflicts, wars, and on-going crises. Too many weak or failing states struggle to cope with internal divisions, corruption, and radicalism, or with polarization between unrelenting regional powers. There are demographic changes, destruction of historic cities, and disintegration of ancient communities. This is a Middle East in a traumatic transition between two orders, one dominated by superpowers and a new one increasingly defined by various regional powers. The questions are the following: who will shape the next Middle East order, and how can the smaller actors survive this transition and secure a better future?

The end of the Second World War marked the beginning of a new world order, where the United States and the Soviet Union established a bi-polar system that drove the evolution of power dynamics across the world. Their Cold War rivalry in the Middle East led to the deep entrenchment of a network of despotic regimes who later became drivers of further evolution in their own region.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 marked the end of the bi-polar world order and instigated major changes across the globe. Eastern European countries, helped by the US and Western Europe, initiated a process of democratization which reached maturity within a decade. Major changes in the Middle East took much longer, however, thanks to the remaining superpower’s poor leadership, the concomitant rise of regional powers, and the region’s own complexity.

In the 28 years since the Cold War, the successive US administrations have failed to adhere to a consistent long-term policy in the Middle East. In broad terms, the Republicans, under the administrations of Presidents George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush, were interventionists with articulated foreign policy doctrines whereas the Democrats, under Presidents Clinton and Obama, were more domestically focused, keeping a relative distance from the evolution of events in the Middle East. The Democratic administrations provided ample space for several regional powers, including Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, to emerge and drive change. Russia too re-entered the Middle East with an impact. It is not clear what policy the Trump administration will adopt for the region but it is unlikely to assume an outright leadership and will not be able reverse the current trend of growing local and regional powers.

Regional Powers

Iran has emerged as the most influential regional power in the Middle East and the only one to have a clear strategy, which it executes hands-on with utter determination. It has now overwhelmed the decision-making processes in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon, and has a solid alliance with Russia.

Turkey, under the ruling Justice and Development Party, has reversed its decades of bad fortune and become a formidable economic and political power. However, it is internally divided and facing great challenges internationally. While in the long term it has the potential to either ascend or decline as a regional power, due to its geostrategic position Turkey nonetheless will always have a role in shaping events, at least across its southern borders.

Israel has always been a major Middle East actor, and is increasingly concerned about Iran’s growing influence. Israel is, by nature, not a passive observer and will mobilize all its political and security instruments to make sure it remains one step ahead of the evolving power shifts.

Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries have collectively gained a significant role, mainly through leveraging their wealth, Arab identity, and Sunni affiliations. The Saudis have become increasingly assertive in the Middle East, North Africa and the Red Sea neighborhood. Currently they are facing significant socio-economic and political challenges at home, including extremism and discontent with the royal family. They also suffered major regional setbacks against Iran’s overwhelming influence, particularly in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen. Nevertheless, they remain determined to limit Iran’s further dominance and to have a big say in shaping the future Middle East.

Egypt has traditionally had a strong political presence among the Arab countries. However, its internal fragility and poor governance system make it more vulnerable and subject to external influence and polarization between stronger neighbors. Indeed, Egypt was one of the early victims of the Arab Spring and, given the depth of its socio-economic and political problems, is unlikely to regain its sense of direction, let alone its significance in the overall power dynamics of the Middle East.

The Local Actors

There are numerous local actors who are also increasingly influential. They include smaller sovereign states, non-sovereign sub-states (such as the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq) and non-state actors. Non-state actors includes those that are socially, politically, or even legally legitimized militias, such as those in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen; and those that are considered, by the international community, illegitimate, anti-state actors, many of whom are part of international terror networks, such as Al-Qaeda. The Islamic State is yet another unique model which emerged as an anti-state terror network in Iraq and Syria and ultimately evolved into an entity with its own independent governance structure. All these local actors are heavily engaged in interdependent alliances, partnerships, or proxy relations with international partners but they still have their own priorities and maintain varying degrees of independence.

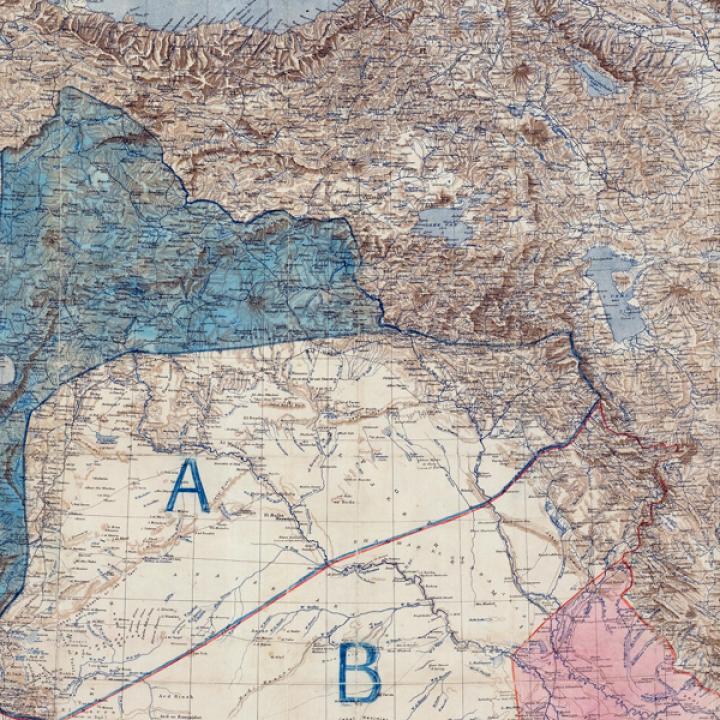

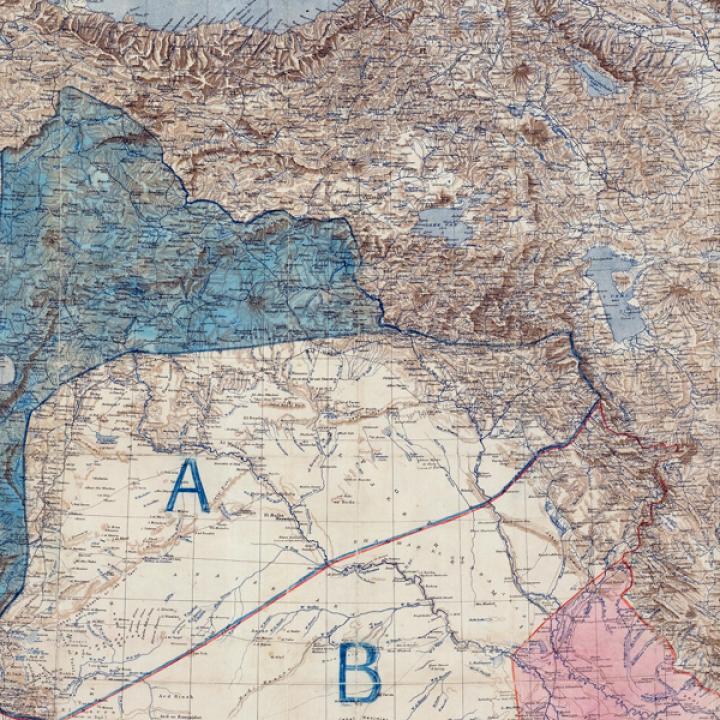

Borders in Transition

The post-colonial borders of the Middle East were drawn almost a century ago, and remained fixed despite the major changes before and after the Second World War and despite numerous regime changes, conflicts, and protracted wars in the region. These lines have nonetheless long been challenged by local actors such as the Kurds, who have long aspired to gain sovereignty. During the current transitional phase, state boundaries have also become blurred and often violated through direct and indirect actions by global, regional, and local actors: they are being crossed by regular armies, militias, mass movement of populations and terrorists

Presently, almost all global and regional actors insist on protecting the current borders; however, they offer no vision on how to protect the people and law and order inside them. In a volatile region where co-existence between communities is becoming increasingly difficult, imposing borders on them will remain an even greater challenge. Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, and Libya are telling examples.

The Middle East is still in flux and will remain so for some time. It may be another decade or more before the region settles into a stable power balance. Meanwhile, conflicts and rivalries will continue. The local actors will inevitably find themselves needing to engage, and at times align themselves, with regional and global powers. However, they are not in a position to change the balance of power and therefore should avoid being drawn into the giants’ rivalries. Instead, they should plan to emerge much stronger at the end of the transitional phase by remaining relatively neutral while investing in good governance, rule-of-law, institutionalization, and inclusiveness.