- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Tracking the Religious Zionist Party Bloc in the Settlements

An analysis of Israel's last five Knesset elections indicates that settlement demographics have played a big role in the rise of Israel's ultra-nationalist, far-right bloc.

Israel’s unprecedented situation of five back-to-back elections provides a unique snapshot into the ways in which political views in Israel have changed over a short period of time while demonstrating the deepening divisions within Israeli society. Perhaps most striking are notable successes of a vocal far-right, religious, ultra-nationalist bloc. While failing to pass the electoral threshold in April 2019, September 2019, and March 2020, this bloc garnered six seats in March 2021 and, most recently, received fourteen seats in this month’s elections, becoming the Knesset’s third largest party.

Such gains follow the general historical trend of Israel’s conservative movement slowly gaining ground over the past half-century. After decades of Labor control of the Knesset, Menachem Begin’s unexpected success as the first non-Labor party PM and his successor Netanyahu serving as Israel’s longest-serving prime minister cemented a shift to the right. The 2021 Israeli Democracy Index—an annual study by the nonpartisan Israeli Democracy Institute—likewise now indicates that approximately 75.9% of Jewish Israelis aged 18-34 self-identify as moderate right (34.9%) or right (41.0%), an almost thirty-point increase when compared to the 56.6% of Jewish Israelis 55 and above who self-identify in these ways.

However, with Likud cementing itself as the country’s establishment conservative party, the Israeli right has also been host to a cohort of more extreme, ultra-nationalist political voices. The results of the March 2021 Knesset elections saw the Religious Zionist Party (RZP)—including the Kahanist Otzma Yehudit and the anti-LGBT-focused Noam Party—now participating in Knesset politics with almost 11% of the national vote.

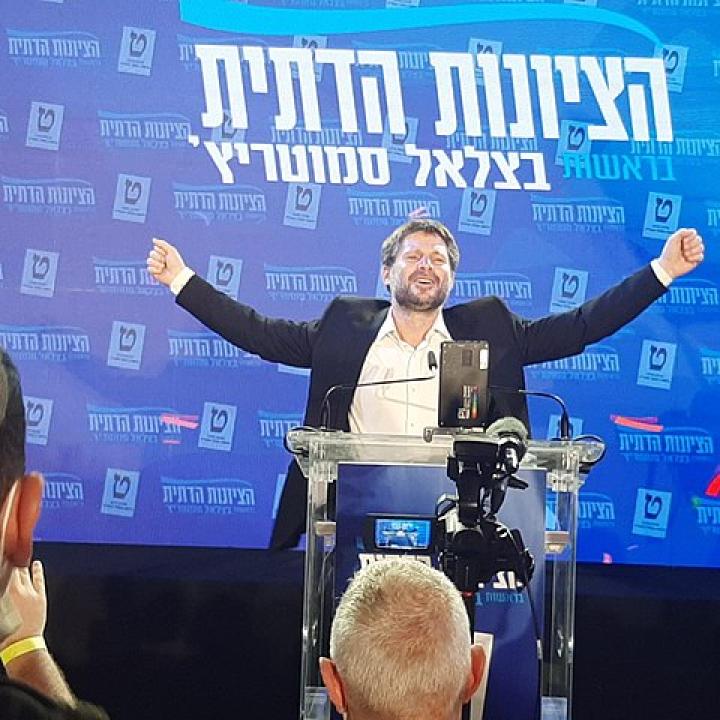

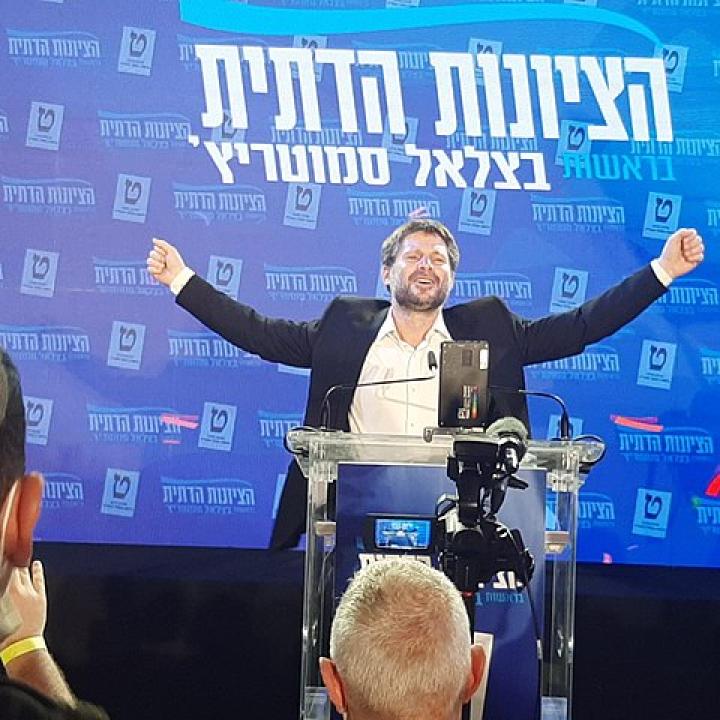

MKs in Netanyahu’s coalition with the RZP include its co-chair Bezalel Smotrich, known for his anti-Arab comments, and others who have promoted anti-LGBTQ legislature or been charged with incitement. In November 2022 Itamar Ben-Gvir joined Smotrich as co-chair of the bloc. Ben-Gvir is also the leader of Otzma Yehudit (Jewish Power)—a Kahanist party now with major representation in the 25th Knesset. Kahanists gain their name from their ideological founder, Meir Kahane, a Brooklyn-born American Jew who, after moving to Israel and being elected to the Knesset, publicly endorsed the expulsion of Arab citizens of Israel and the establishment of Israel as a Jewish theocracy. Several of Otzma’s members have been barred from running in Knesset elections due to racist remarks and activities. One incident in 1995 when Ben-Gvir was a teenager included stealing the hood ornament from soon to be assassinated Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s car and cajoling that “if they could get to his car, they could get to him.”

Otzma failed to pass the threshold for entry into the Knesset as an independent party in the 2013 and 2015 elections, and did not rank high enough on a joint list with the Union of Right-Wing Parties (URWP) when the bloc gained five seats in the April 2019 elections. In the subsequent two elections, Otzma ran independently and failed to pass the threshold again. As such, their arrival in the Knesset in March 2021 and their explosion in November 2022 marks a particularly concerning aspect of the RZP’s bloc.

Popularity in the Settlements

At least some of the RZP’s success can be attributed to the strong support for the joint list of RZP, Otzma, and Noam has gained among settlers—both east and west of the security barrier. In settlements, RZP garnered 22% of the vote during this most recent election, over twice the national total.

While the success of the RZP amongst settlers indicates a high degree of right-wing solidification, the total voting population in the settlements is a small fraction of the total Israeli voting population. Only 5% of Israelis live in settlements (excluding East Jerusalem) and one can expect the percentage of Israeli voters living in the settlements to be even lower due to their lower median age. According to the settler newspaper Arutz Sheva, 48% of Israelis living in Judea, Samaria, and the Jordan Valley are over the age of 18 compared to 71% of the national total. Taking these estimates at face value this would mean a bloc consisting of less than 3.5% of the national eligible voting population accounted for 6% of the RZP’s votes. Attention should also be brought to the “double envelope” votes—mostly IDF soldiers as well as some hospital patients, prisoners, Israeli diplomats, and senior citizens—which comprised 13.7% of the RZP’s vote, and Jerusalem residents (7.3%). Nevertheless, the settlement bloc is rapidly growing, meaning that understanding its voting patterns will be increasingly important.

On the one hand, the settler population is by no means politically uniform, either between settlements or even within them. For example, in Karnei Shomron (an Israeli settlement 15km southwest of Nablus), 54% of votes went to the RZP but the centrist Yesh Atid still received 3% of votes. However, the consolidation of the Religious Zionist bloc during the last two elections has likewise solidified settlement support for the bloc. Across all five elections from April 2019 to November 2022, support for Otzma or the RZP ranged from 17.9% to 27.0% west of the barrier and 46.2% to 63.7% east of the barrier. However, the uniting of this Religious Zionist block created a powerful voting force in the settlements. Moreover, from March 2021 to November 2022, the RZP increased their share west of the barrier by 8.2% and east of the barrier by 13%.

Support for the RZP bloc has now noticeably concentrated in settlements east of the barrier. Whereas Yamina held 43.6% percent of the vote in September 2019 elections, the majority of voters in settlements now support the RZP (59.7%) whereas Jewish Home—Yamina’s successor—garnered just 4% of the vote. Support for Jewish Home west of the barrier is even lower (3.4%), although the RZP’s share of the vote in these areas is less decisive with 22.4% of the vote. When the large majority-Haredi settlements of Beitar Illit and Modiin Illit are removed from the dataset, support here jumps up to 31.54%.

The remaining votes are spread between the Haredi religious parties (Shas and United Torah Judaism, or UTJ), the Russian secular party, Yisrael Beiteinu, and, in March 2021, Gidon Sa’ar’s anti-Netanyahu party called New Hope. In the Haredi communities of Modiin Illit and Beitar Illit, support for the Haredi religious parties is two to three times greater than in other settlements west of the barrier. By contrast, settlements both east and west of the barrier voted for New Hope and Yisrael Beiteinu in relatively equal numbers.

The continuation of current election trends is not an inevitable conclusion. The period of five consecutive elections has had a polarizing effect on voters, suggesting that this trend could reverse if elections return to a more standard schedule. Yet the arrival of the RZP and Otzma to the Knesset, first in the opposition and now likely in the ruling coalition—helped by a significant amount of support from settlement voters, especially those east of the settlement barrier—suggests that this new force in the Knesset is likely to grow if it continues to maintain their support based on demographic trends in the settlements. Since 2017, the settlement population has grown by 13% compared to the 8% population growth overall. Thus, as the settler population grows, right-wing, ultra-nationalist, and religious parties’ representation in the Israeli political and public sphere will likely also expand.

In other words, the solidification of far-right parties amongst settlers and the growing settler population creates a symbiotic relationship resulting in the mainstreaming of previously-considered “fringe groups.” The RZP and similar parties will not gain a plurality of votes any time soon. However, given Israel’s many parties and complicated coalition building process, small Knesset parties have increasingly had an outsized impact on policymaking, as demonstrated by Netanyahu’s inclusion of numerous small Haredi parties in his coalitions or—most recently—Yamina’s own meteoric rise to coalition builder with just seven seats.

On the other hand, electoral victory does not necessarily translate into political power—the extreme policies of the RZP were one of the main reasons Netanyahu was unable to form a coalition during the previous round of elections, and it remains unclear how and where Netanyahu will make concessions to his new coalition partners this time around.

Either way, the fact that 14 of the 120 seats in the Knesset belong to ultranationalists should give Israelis pause. The recent Arab-Jewish conflicts within Israel and the ongoing animosity between Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank open serious questions about the long-term relations between the two national groups. The prominence of parties like the RZP, perhaps a reflection of the cynicism born out of aborted peace negotiations and the trauma of the Second Intifada, only further highlights these divides. It remains to be seen if the RZP’s consolidation amongst settlers is nearing its peak—and if support from other Israelis is a transient phenomenon—or if it is a harbinger of an increasingly radical, polarized Israel.