- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

The Abu Ragheef Committee Crisis: Security Repercussions for Iraq

The repercussions of the Abu Ragheef committee are still playing out in Iraq, as the Sudani government attempts to assign blame and pursue justice.

A Washington Post investigation published in December 2022 found that Iraq’s Committee 29, also known as the Abu Ragheef Committee, had “used incommunicado detention, torture, and sexual violence to extract confessions from senior Iraqi officials and businessmen.” The Post investigation drew upon more than 20 interviews with persons detained by the Abu Ragheef Committee. These interviews revealed that detainees had been subjected to “abuse and humiliation, more focused on obtaining signatures for pre-written confessions than on accountability for corrupt acts.” One former detainee stated that the violations and abuses they endured at the committee’s hands included being stripped naked, choked with plastic bags, tortured with electricity, and more.

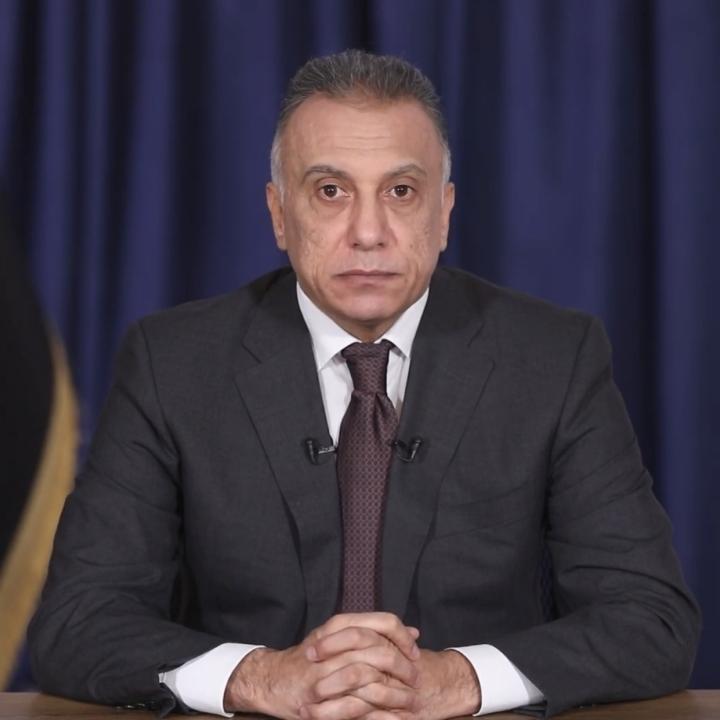

The Abu Ragheef Committee was established in 2020 by former Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi with the purpose of fighting corruption and organized crime in Iraq. By March 2022, however, the Iraqi Federal Supreme Court ruled to dissolve the Abu Ragheef Committee, declaring it unconstitutional on the basis of reports that the committee members violated human dignity and the principle of separation of powers. In June 2023—roughly six months after the Iraqi government established its own special investigative committee in the wake of the Washington Post’s report—Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani finally endorsed the investigative committee’s recommendations to look into victims’ grievances against key members and leaders of the Abu Ragheef Committee.

However, the ramifications of the Abu Ragheef Committee’s actions and the implications of the Committee's closure have yet to fully play out. The most important operations carried out by the Committee included detaining the former director of Iraq’s Pension Fund, the former head of the Baghdad Investment Commission, and the former director of the electronic payment company Qi Card in September 2020. Following their arrests, these figures were given prison sentences of varying lengths by the Iraqi judiciary, under which the Abu Ragheef Committee operated. Now, significant questions surround the fate of those prosecuted and sentenced by the committee.

Though the committee’s affiliation with the Iraqi judiciary may have given it a semblance of impartiality and legitimacy, the evidence suggests otherwise. Case in point, members of this committee in particular saw their funds multiply as reported by the investigative committee. Also, the Director of the office of Abu Ragheef, Brigadier General Salem Al-Daini, was openly accused of carrying out torture operations while working on the Committee and was arrested in mid- January at Baghdad International Airport while trying to flee the country. And though the committee’s legal procedures might have taken place under the auspices of the judiciary, its security and intelligence procedures were under the exclusive oversight of the former director of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service, Ahmed Taha Hashim (a.k.a. Abu Ragheef.)

Considering the committee’s murky legal standing, will those sentenced be retried? Will they be released despite evidence issued by the Iraqi courts against them? Moreover, there are numerous figures who are still under investigation for proven crimes of financial corruption. Will these detainees be released or reinvestigated? How will the allegations of forced confessions and torture weigh out against any irrefutable evidence against them?

On a larger scale, Iraq must also contend with questions of fault and institutional blame. Though the Abu Ragheef Committee is at the center of this crisis along with the Iraqi judiciary, the buck stops with Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who should have placed the committee in the hands of professional judges rather than Abu Ragheef. The Iraqi public prosecutor should have been directly monitoring the committee’s work on a daily basis and investigations should have been carried out by forensic investigators who specialized in anti-corruption cases. The Abu Ragheef team and its security forces could have been entrusted with carrying out arrests and seizing evidence, but not with legal investigations or sentencings. Kadhimi’s failure in implementing legitimate, legal anti-corruption measures in Iraq reflects his limited experience in the security and judicial spheres, despite his long experience in the Iraqi government.

Now, the Sudani government must decide how to address the violations of Abu Ragheef Committee members. These members possess significant databases and hard evidence against various entities and public figures involved in corruption and organized crime, and by putting them on trial, the government will inevitably be revealing this evidence to the public. The Iraqi judiciary would then be obligated to investigate the evidence and carry out necessary legal procedures, which could drag on for years and impact dozens of defendants, effectively leading Iraq back into the same mess it currently faces.

In order to mitigate the repercussions of this crisis while also pursuing justice, protecting the rights of detainees, and correcting the Abu Ragheef Committee’s misguided course, there are several steps that Sudani should take. First, he must give directions to form a judicial committee responsible for studying and evaluating the cases for investigation that the Abu Ragheef Committee had referred to the Iraqi courts. This judicial committee should then verify the evidence presented and examine to what extent it aligns with the confessions given. This will make it possible to sort out which cases can be reinvestigated and which cases are closed. These latter cases cannot be reinvestigated if no flaws have been identified in the investigation, as per the Iraqi Code of Criminal Procedure.

Sudani should concurrently order the Ministry of Interior to investigate accusations that Abu Ragheef Committee members misused their power and lined their own pockets during the course of the committee’s operation. The outcomes of these procedures will create a clearer picture of the situation for everyone and allow the Iraqi government to pursue justice as necessary.

Above all, the Sudani government must learn from the grave mistakes of the Kadhimi government and the Abu Ragheef Committee. Moving forward, the Iraqi government must approach anti-corruption measures with the utmost care, entrusting them to the constitutional institutions that already exist to address these issues and enhancing their capacities to do so. The Sudani government must avoid assigning advisors to roles that fall outside their professional expertise, because in the end, it is the prime minister alone who will be held responsible for any violations committed.