- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

The Continuing Threat of ISIS in Iraq after the Withdrawal of the International Coalition

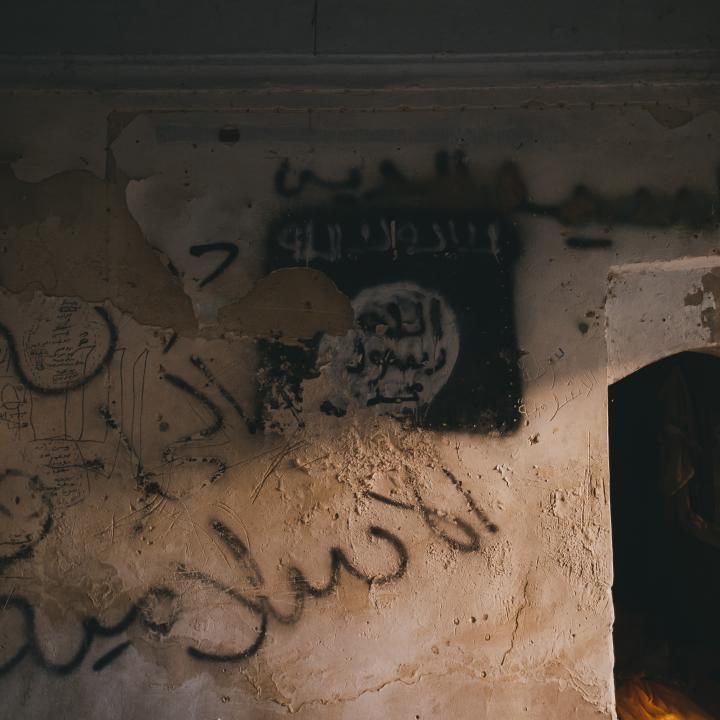

Without active and continuous deterrence, ISIS forces may look to take advantage of the deteriorating security and governance situation in areas formerly under their control.

After the toppling of Saddam Hussein's regime in 2003, Iraq faced the challenge of rebuilding the state first and foremost, along with political, economic, and social challenges that needed to be addressed in order to strengthen national identity. This was in order to contain the charged social and regional divisions alongside the behavior of the previous regime, which reached its peak interaction with the American invasion of Iraq. Moreover, terrorism represented a unique problem for Iraq that competed with and topped other issues through two waves that later spawned sectarian fighting, turning Iraq into a focal point for extremist Islamic groups and armed factions that emerged to fight the American presence and undermine the ongoing democratic process.

Now, a new withdrawal of U.S. forces is under discussion; officials from the Sudani government in Baghdad have confirmed that negotiations with the Americans began in February, with the U.S. demanding assurances against the return of ISIS as part of this process. However, a discussion of the security and military challenges this withdrawal will pose for Iraqi forces is necessary, highlighting that the challenge of extremism is not solely military but also stems from social grievances among Iraq's main community components. After its military defeat and the destruction of its urban networks, the Islamic State still maintains a presence in rural desert areas, constituting its main support base. Without active and continuous deterrence, these forces may look to take advantage of the deteriorating security and governance situation in areas formerly under their control.

Iraq’s Reliance on Foreign Forces: A Brief History of the Need and the Dilemma

After the American invasion of Iraq and the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime, and with President George Bush declaring the end of combat operations, armed attacks against American forces intensified under the guise of resisting occupation. These quickly morphed into jihadist groups adopting Salafi doctrine, previously insignificant in Iraq's social structure before 2003. The Zarqawi group—an offshoot of Al-Qaeda—specifically underwent significant organizational and methodological changes, eventually becoming the "Islamic State of Iraq.”

This period demonstrated that President Bush's statements declaring victory were far from reality; American forces, aided by newly formed Iraqi units, notably the CTS, pursued Zarqawi and his organization until his death in 2006. The American forces likewise collaborated with tribes in Baghdad, Anbar, and other Sunni-majority areas, forming what became known as the Awakening Councils. Through American training, funding, and support, these councils defeated the Islamic State organization, pushing it into the desert. In return, the Awakening Councils received promises of integrating into Iraq’s official security forces, ending the first chapter of direct American-Iraqi military and security cooperation in December 2011.

Following the American withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 and as the capabilities of the Iraqi security forces declined, ISIS exploited this period to rebuild its efforts and capabilities. Meanwhile, the politicization of military leadership meant replacing competent leaders with more loyal individuals, adding to overall decreased combat abilities and morale. Effectively, the space given to extremist groups after the first American withdrawal due to this process led to a security collapse after the Islamic State's attack on Mosul in 2014, allowing the organization to take over large parts of Iraq.

ISIS’s territorial gains prompted President Barack Obama to form an international coalition of 87 countries and organizations to fight the Islamic State (ISIS), bringing foreign forces, led by the Americans, back to Iraq in what was known as "Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve CJTF-OIR". Iraq's National Security Advisor, Mr. Qasim al-Aaraji, mentioned that the government needed friendly forces to assist in its fight against the organization, which had become a significant threat to the entire country. The United States also provided military aid through the coalition, including equipment and vehicles, relying heavily on the Counter-Terrorism Service and security forces ready to work with Americans. The United States also helped the Iraqi government take significant steps in restructuring its security forces, combating corruption, and human rights abuses, in cooperation with then Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, funding various units, formations, and programs through several U.S.-managed programs and laws.

By 2017, Iraqi forces, with the help of the international coalition, managed to militarily defeat the organization. With the threat of extremism once again diminished, calls from some political forces to expel foreign troops, especially American forces, emerged in Iraq. This led to a vote in the Iraqi parliament on the issue despite lacking the legal quorum. The foreign forces shifted from combat to non-combat roles in December 2021, including training, advisory, and intelligence support. In a briefing by General Matthew McFarland in August of lastyear, he emphasized the limited role of coalition forces, stating, "Military operations are only one lever key to the defeat of Daesh, and within CJTF-OIR as a military organization, this is where we focus our efforts: on the military security aspect."

In 2023, demands resurfaced for the withdrawal of foreign, notably American, forces from Iraq. These calls were driven by a group of political parties whose armed groups, supported from abroad, targeted American bases and logistical convoys with drones, Katyusha rockets, and roadside bombs.

Addressing the Threat of a Vacuum

It is true that Iraqi forces have evolved and are more capable of confronting any resurgence of the organization. Nevertheless, the American withdrawal may create a vacuum in central and northern areas of the country, potentially filled by externally-backed armed groups, reminiscent of the pre-2014 scenario of Sunni rebellion and the organization's claim of "protecting Sunnis," pivotal in the Syrian civil war and Iraq. Given this potential outcome, the withdrawal should not be hasty and should be sure to deliniate future, lasting security cooperation with the United States.

In particular, the withdrawal raises questions about the process of transferring coalition tasks, especially ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance), to NATO's mission in Iraq, and whether Iraq will later demand NATO's withdrawal. It has been argued that NATO's presence would not sustain without American forces and would logistically need to leave, as opposed by anti-American party leaders.

However, the concerns are broader than just security issues. Iraq’s Sunni component is caught between self-withdrawal and mobilization. Political mismanagement and weak governance in a diverse country inevitably leads to grievances among societal components, fueling conflict especially if neglected by the government, and thus providing fertile ground for exploiting these grievances by extremist elements.

Post-American withdrawal in 2011, Sunni political entities involved in counter-terrorism faced allegations of "Sunni victimhood.” Extremist groups exploited the erosion of support for these forces and took advantage of governmental malpractices in Baghdad—including random arrests and human rights violations—to draw disillusioned youth towards extremism. Awakening Council forces, once allied with government and American forces against ISIS, faced similar persecution and unfulfilled promises of integration into the official security forces after their role in combating ISIS.

There was nothing inevitable or intrinsic to Iraqi Sunni society that prompted this shift. Despite the Islamic wave that started in the 1990s—leading to Salafi movements, secret organizations, the spread of Abdullah Azzam's tapes, and the emergence of Ansar al-Islam in northern Iraq—Iraq was never fertile ground for Salafi doctrine, nor did it have a distinctly Islamic identity. However, within two years, the most ruthless extremist organization in history emerged on the Iraqi scene. This organization didn't require an ideological environment as much as it sought to inflame the sectarian conflict that had become entrenched by some government practices in Baghdad. Following Abu Bakr Naji's strategy of "Management of Savagery," the organization exploited Sunni grievances in Syria and Iraq, presenting itself as the savior for the Sunni component.

Many Iraqi youths who joined the organization were not Salafis or even religious; their motivation was revenge for the violations of trust and security that they suffered under poor governance. This, after a significant Sunni rebellion that the Baghdad government failed to contain, led to the Islamic State regaining control over vast Iraqi territories, which some in that community ignorantly welcomed.

There is the fear that given the current state of Iraqi governance, history will repeat itself. Recent analysis of the situation in Sunni-majority areas indicate a return to the pre-2013 atmosphere of violations and arbitrary practices by externally-supported armed groups. A source (who requested anonymity) mentioned that the security situation in Diyala province is very concerning, with the state unable to protect civilians while drug trafficking, protected by externally-supported armed groups, is active there. In Anbar, Salahuddin, and parts of Nineveh province, the situation is similar.

Despite suffering great social grievances and illegal practices, some components, especially in Sunni communities, would refuse to accept the Islamic State as an alternative to the injustice they face. However, it does not mean others in these communities will look to external actors to protect their communities as their trust in the state dissolves, and push both sides towards conflict. The American withdrawal will likely enhance the spread of armed groups and widen the scope of violations against the Sunni community. The Islamic State, benefiting from the withdrawal, will exploit this situation.

A Question of Security Forces’ Long-Term Capabilities

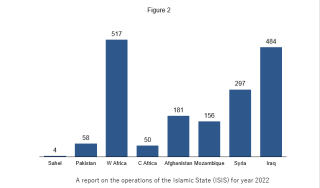

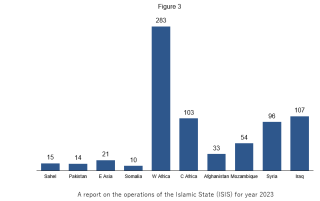

Following calls for foreign troop withdrawal and coalition mission termination, the U.S. requested guarantees from the current Iraqi government led by Mohammed Shia al-Sudani to prevent the organization's return and ensure Iraqi forces' readiness. Despite setbacks between 2018-2020 under a government opposed to U.S. presence, progress resumed under Mustafa al-Kadhimi, albeit slowly. The Islamic State's operations have significantly decreased after its 2017 defeat, transitioning from a centralized network to decentralized cells operating stealthily.

Coalition airstrikes on Islamic State targets have dropped to their lowest since the coalition's formation, with combat operations ceasing in December 2021. Yet, the Islamic State remains in many Iraqi areas, posing a threat contrary to Iraqi officials' statements prioritizing drug combat.

Observers recognize that the issue with Iraqi forces is not their immediate readiness to maintain the defeat of the Islamic State, but rather their ability to maintain these capabilities long term if American support ceases. Iraqi forces, significantly developed post-2003 with American help, gained experience in counter-insurgency, raids, and counter-terrorism, especially units like the Counter-Terrorism Service supervised by U.S. military leadership. However, the 2011 U.S. withdrawal, due to emergency intervention policies and avoiding permanent security cooperation, left Iraqi forces vulnerable to political dynamics that eroded their combat ability, training programs, and military sector deployment, leading to political and sectarian bias over professional competence. The Islamic State has demonstrated that it knows how to take advantage of this situation when it restructured and rebuilt its efforts and orchestrated the Iraqi forces' military defeat in 2014.

The Essence of the Situation: What Matters Most

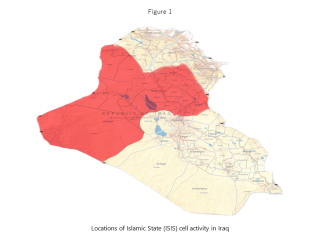

Despite the defeat of the extremist organization in Iraq and Syria and the security developments in tracking and eliminating its leaders, the ideological legacy of the organization has not dissipated. Its cells still operate in a decentralized manner, especially in regions like Salahuddin, Anbar, Diyala, the Baghdad Belt, and the Jazira area. Fighters in prisons remain loyal to the organization, and its operations continue at varying rates in several areas. General Matthew McFarland, commander of Operation Inherent Resolve, highlighted in August 2023 that ISIS's malignant ideology still intact, posing a potential for resurgence. Iraqi officials, however, believe the organization no longer poses the threat it did a decade ago, considering its comeback unlikely.

After the last battle in Baghuz and the "oath of death" proclaimed by its fighters in 2019, the first generation of jihadists who led the organization in its early stages in Iraq and Syria ended, with the survivors relocated to prisons in northern Syria. This significantly reduced the organization's capacity, unable to protect its leaders from international coalition strikes, and internal disagreements over the leadership legitimacy emerged, delaying the announcement of its latest leader, Abu Hafs al-Hashimi.

Attempting to rebuild, the organization attacked the Ghweran prison in Hasakah to free its most dangerous fighters, reminiscent of the 2013 "Breaking the Walls" operation at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, which resulted in over 500 organization members escaping, including leaders who later formed the foundation of ISIS and its subsequent large-scale attacks. Despite the failure of the Ghweran prison attack, the organization desperately needs its fighters to rebuild its efforts, with the first priority being reunion with their families in Al-Hol and Al-Roj camps, then regrouping in the Anbar desert.

The bigger challenge now is addressing the extremist ideology and ideas that have become the organization's legacy. Social grievances have led to armed violence and provided extremists an opportunity to exploit these issues, tarnishing the national identity. Iraq has not made significant progress in combating the ideology of the organization; nor is there any talk of establishing a clear strategy for addressing these issues beyond security approaches. The American forces, despite ceasing combat missions, are currently suffocating the organization's military capabilities. Nevertheless, the organization thrives in desert and rural environments, where unemployment, backwardness, lack of health and educational services, ignorance of Islamic concepts, and the harsh nomadic life contribute to the perpetuation of this ideology.

Meanwhile the situation in Al-Hol and Al-Roj camps in northern Syria, housing families of the extremist organization alongside its larger refugee population, is seen as a ticking time bomb and incubator of the next generation of jihadists. There, the organization is succeeding in indoctrinating and raising its children according to its extremist principles. With thousands of organization members in Syria who have not faced trial and limited executions of its members in Iraq as is required according to Iraqi law, the threat of the organization's resurgence—especially with its leader reportedly in Iraq—should be raising deep concerns about its future plans.

The organization will continue to work to exploit the Sunni protection issue in Iraq, reflecting the political tensions affecting the likelihood of limited conflict and hatred. As such, the Sunni component's reaction to political tensions and violations, compounded by the American withdrawal, should be a primary concern. The withdrawal of foreign forces now would end the efforts to ensure the organization's lasting military defeat, reintroduce the risks of its resurgence, and potentially lead to further turmoil, including possible American economic sanctions due to unhealthy relations with neighboring countries.