- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

The Future of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria after the Killing of its Latest Caliph

Following the killing of ISIS leader Abu Ibrahim Al-Quraishi, the organization will try to regroup and move forward, but replacing its leader will pose unique challenges.

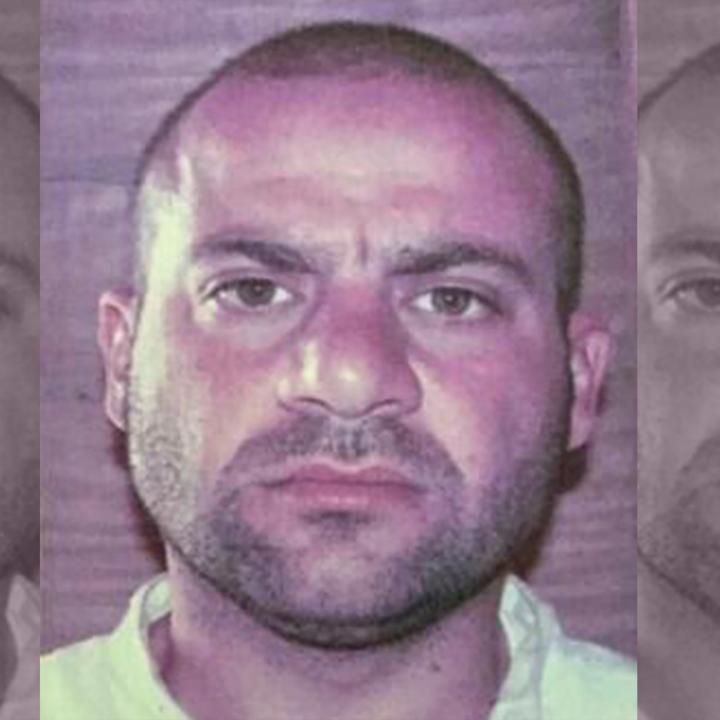

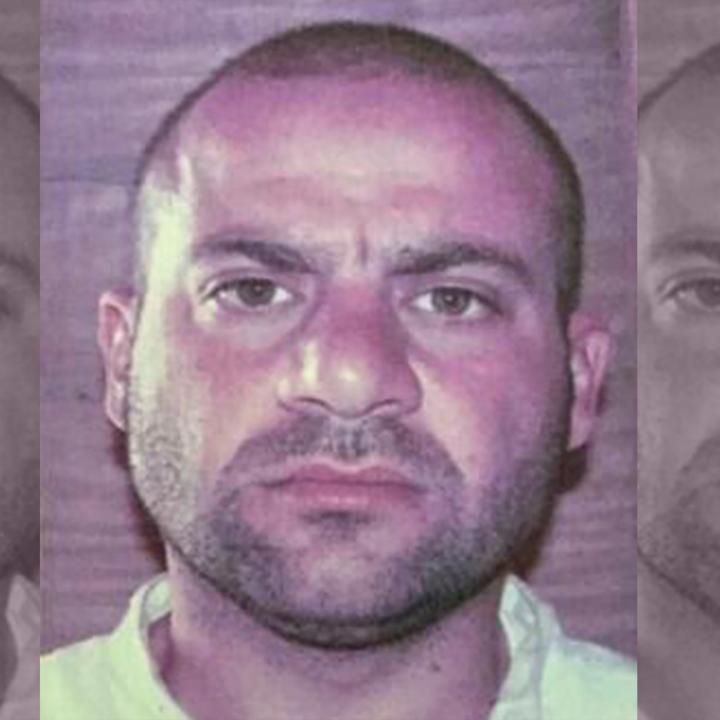

On February 3, US President Joe Biden announced the killing of the leader of the Islamic State (ISIS). While the killing of Abu Ibrahim Al-Quraishi or “Abdullah Qardash” is an important event, a great security achievement, and a major setback for the organization, as it will limit its movements in both Iraq and Syria, it seems that these negative impacts may not last long.

ISIS is accustomed to adapting exceptionally quickly to the organizational shocks and killings of its senior leadership. It is therefore imperative to understand the factors ISIS relies on and which hold the group together whenever it loses a major battle or a first-line leader fall. ISIS is a complex creation that developed with remarkable speed and established itself under exceptional circumstances. Its response to these events represents a notable breakthrough from other jihadist groups, since it relies on fundamental practical catalysts that shape its decisions regardless of its operational strength.

Strategic and Ideological Catalysts

After the ISIS caliphate was eliminated and the territory it controlled was recaptured in 2019, many predicted that the organization was moving towards extinction or disappearance—as occurred with Al-Qaeda. This prediction was based on comparing the two organizations ideologically and identifying similarities between them. Yet while the religious ideology is similar, the form and practical theory of the ideology differs significantly. The practical theory of ISIS is based on the outputs of hardline Salafi religious thought but continues to be the transformative element that brought ISIS to the seat of the caliphate and transformed it from armed groups to a large army in record time.

ISIS strictly adheres to a long-term strategy continuously reviewed and developed to keep up with changing local and regional situations and protect the organization from collapse. For example, applying the principle of decentralization in field operations gives military commanders great freedom to carry out terrorist attacks as they see fit and in accordance with the surrounding conditions. Decentralization also allows field commanders to secure a large share of funds and enhance horizontal recruitment operations in the communities they live in.

This strategy ensures ideal adaptation to surrounding conditions, prevents disintegration, and supports recruitment. The “silence and disappearance” strategy ISIS follows when there are security pressures or government military units conducting large-scale campaigns against the organization from time to time has helped keep it out of sight.

ISIS jurisprudence of jihad is modern and uncodified, unlike that of Al-Qaeda. ISIS relies heavily on Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir’s jurisprudence of jihad, which allows for the killing of anyone at any time and for any reason in order to reach the sought-after caliphate.

Media and Political Catalysts

ISIS focuses its political appeals and media statements on the oppression and marginalization of Sunnis in both Iraq and Syria. Its predecessors in Iraq depended on “cautious recruitment,” or “elite attraction,” for fear of disintegration or infiltration. But after Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi took leadership in 2010, ISIS focused on expanding the scope of recruitment. Adopting “diverse” or “mass” recruitment led to a surge of fighters, whose numbers reached 300,000 in Iraq and 50,000 in Syria by 2014. Despite reduced media production and its limited spread compared to the past, ISIS media discourse still has a following among thousands of Muslims.

The media catalyst helped a lot in developing and forming popular constituencies for supporting the organization, and these constituencies developed and took two forms, direct (supportive) or indirect (potential) forms.

This strategy has brought ISIS both direct supporters of the organization—who are spread across some Sunni areas of Iraq and Syria that suffer from marginalization and exclusion—and potential indirect support bases that neither announce loyalty or opposition to ISIS. Both constituencies are located in areas controlled by ISIS, or in areas where ISIS circulates with a great deal of freedom. They are a present or future fertile ground for attracting new members, and a wide space for ISIS to implement its new strategy.

Aftermath of the ISIS Caliph’s Killing

A close look at the biography of radical jihadist groups in general, and ISIS in particular, confirms that the killing of commanders or leaders does not necessarily mean an imminent end to the group or its ideology. The central strength of ISIS, and the abilities of its branches, does not only revolve around its leaders. It is based on a number of structural fields and variables, such as recruitment, strategy, attraction, and mobilization. Therefore, the killing of the ISIS caliph (Qardash) is nothing more than another military defeat for the organization in a continuing, long-running war of attrition, led alternately by central governments and ISIS itself. Previously, ISIS lost its state in Iraq and Syria, thousands of its leaders and followers were killed, and thousands more are still languishing in prisons. The organization lost the ability to mobilize, and its funding was greatly limited. Even so, it has been able to restructure itself again in less than two years and start launching effective attacks in both of the aforementioned countries.

However, appointing a new caliph is vital for linking the personnel of the formations and groups associated with ISIS and preventing defections. It is also key to continuing to achieve political gains and implementing the main strategic objectives that were the basis upon which it announced the caliphate. Without the caliph, ISIS becomes a regular local organization that has lost its regional and international standing. Such a loss could even lead the organization to end up pledging allegiance to Al-Qaeda once more. Hence, the position of the caliph is a propaganda factor dedicated to the concept of the caliphate, even if ISIS has been unable to implement it in reality.

It is worth mentioning that Quraishi was not chosen with the consensus of the military and religious leaders within ISIS. He assumed the caliphate based on the desire of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who announced him as caliph before his death. That is, the selection was imposed on the rest of ISIS leadership. It appears that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi sought in his recommendation of Quraishi as successor to avoid splits within the organization in the event that he was killed.

Since Quraishi did not do the same during his life, the possibility of a delay in announcing a new caliph and the emergence of a leadership crisis within ISIS has become more likely than during the previous succession. It is also possible that one of the remaining leaders in the Shura Council and the Delegated Committee will take over as the new caliph, The most prominent of these are Jabbar Salman Al-Issawi, Juma Awad Al-Badri, Bashar Ghazal Al-Sumaida’i, Sami Jassim Muhammad Al-Jubouri and Fayez Okal Al-Nuaimi Al-Quraishi.

Above all, ISIS wants to choose a caliph with strong charisma and a clear Quraishi lineage. Moreover, the organizations wants a caliph who all agree on, just as they agreed on Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, who was able to take ISIS from a local Iraqi security organization to an international organization controlling vast territory in 2014. But this may be difficult today, especially since ISIS is suffering from a leadership crisis, one that has increased since losing most of its veteran leaders from the first generation who were contemporaries of al-Zarqawi and al-Baghdadi.

Either way, appointing a successor to Quraishi will take longer than the previous transition, and even if the possible caliph were to be announced in the coming few days, it would take time for security leaders within ISIS and leaders of the organization’s provinces (wilayat) around the world to acknowledge them, and for the new leader to gain approval from jihadi theorists loyal to ISIS. Other complications include voices within ISIS-associated groups in Iraq and Syria about the appointment of a caliph who is not of Iraqi nationality. This is something the Shura Council and Delegated Committee tasked with appointing caliphs may take seriously to stave off defections within ISIS or the organizations loyal to it in many countries.

The selection of a new ISIS leader is inevitable, but the choice will have numerous repercussions this time around. The very future of ISIS in Iraq and Syria has become dependent on the name and standing of the new caliph. At a time when ISIS is trying to rebuild its terrorist groups and start reasserting influence in many territories and areas of Syria and Iraq, any crises or an extended delay in choosing a caliph without leadership consensus can have profound repercussions on its continuity.