- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Hurdles for the Iraqi Parliamentary Election

Uncontrolled weapons are the most prominent barrier to the electoral process, along with insufficient international observation to ensure free and transparent elections.

Currently, the Iraqi government is insistent that the parliamentary elections scheduled for October 10 will be held on time. In addition to the Iraqi High Electoral Commission’s assurances, Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi has reiterated on multiple occasions that the elections will not be postponed. Yet it is likely that the matter is not so set, and that these decisions may change quickly. This very thing has happened in other important and serious instances, including the issue of applying the law and curtailing the role of provincial factions rebelling against the government that impose their will on political, parliamentary, and day-to-day life in a country that has been without reassurance for more than two decades.

Moreover, there are several major obstacles to the elections being held on schedule. After over fifteen years as a journalist covering Iraqi affairs, the barriers that exist justify my presumption that elections will not be held on time.

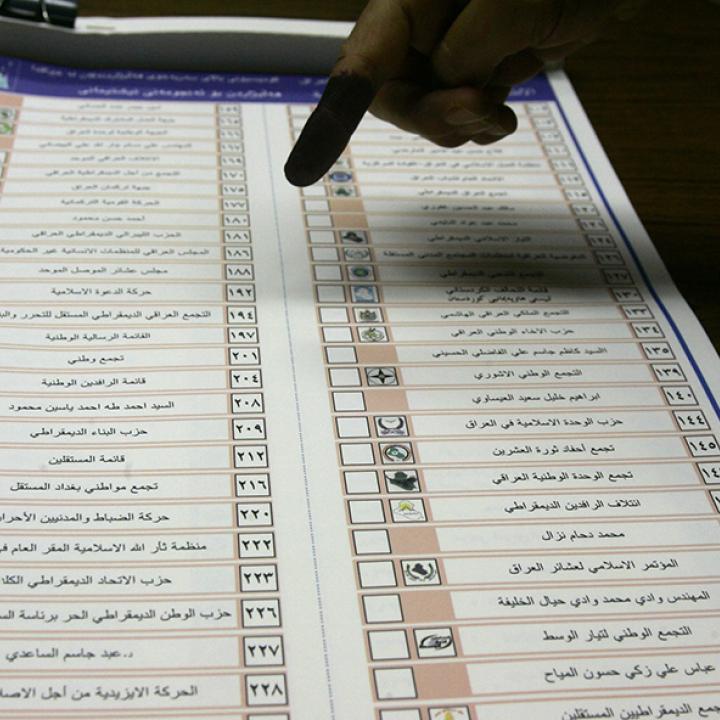

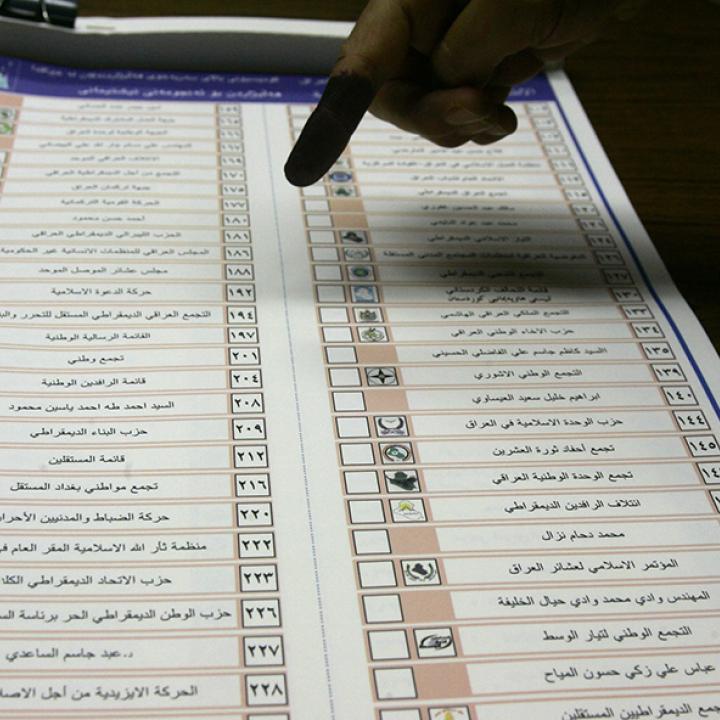

Uncontrolled weapons are the most prominent barrier to the electoral process. It is impossible to imagine fair and transparent elections in the current atmosphere, with uncontrolled weapons belonging to forces that are not interested in promoting Iraq’s stability. Proof of this is the continued targeting of the international missions operating in Iraq by armed factions claiming to belong to the official forces in Iraq, as well as continued assassinations throughout the country, especially of youth activists of the October demonstrations and others. In this context, the greatest problem arises in the control that political groups belonging to those armed forces have over the current parliament and their ability to threaten citizens into electing figures affiliated with them. This is what occurred in the past election of 2018, and is one of the reasons so many Iraqis called for new elections in the first place.

Even outside of politicians linked to militias, it is well established in Iraq that public money is used to encourage participation in elections. For this reason, there are forces and candidates who view the position as a source of plunder rather than as a tool to serve the republic and the country. Accordingly, these entities spend considerable sums on their electoral propaganda in the hope of recouping the funds spent through corrupt contracts and quid pro quos in future dealings in a country suffering from planning paralysis and financial corruption, and which—according to some government officials—has wasted more than a trillion dollars. These funds not only have an impact in changing the will of the voters, but also the results of the counting and sorting after elections by buying off some employees and those controlling the election results.

Aside from pressure to vote in a particular way, it is also expected that the outcome of the elections will be rigged, and the results tampered with. There are even some allegations that the figures who will win the upcoming elections have been settled, and that the present dispute is only over those 30 percent of names that have not yet been determined.

Although the Sadrist movement was poised to make the biggest gains in the early general elections scheduled for October and to gain the premiership, Sadrist leader Muqtada al-Sadr announced on camera in mid-July that he would withdraw from participating in the upcoming parliamentary elections. “For the nation,” as he said, “is more important than all of that . . . I announce that I am withdrawing my hand from all those affiliated with this current and upcoming government, even if they claim to belong to us, the family of Sadr.” The Sadrist movement’s withdrawal could be seen as an attempt to twist the arms of the rest of the political powers, as in al-Sadr’s withdrawal speech he announced that he did not support any party in the legislative elections.

However, it appears that this tactical move is intended to extract promises from their partners that the movement can take the most important and prominent position in post-2003 Iraq: the position of prime minister. This decision may involve a reshuffling of the Sadrist movement’s cards, given some polls indicating a significant decline in al-Sadr’s popularity. Previous experiences have proven that al-Sadr is not steadfast in his positions, which is why he may retract in the final hours. Former Deputy Prime Minister and former member of the movement Baha al-Araji stated on August 8, 2021 that the movement would participate in the upcoming elections.

Sadr’s withdrawal (in the media, not officially) was followed by withdrawals that included the Iraqi Communist Party, the head of the National Dialogue Front Saleh al-Mutlaq, and former Prime Minister Ayad Allawi, in addition to many non-prominent candidates. However, the Electoral Commission has confirmed that it did not receive any written requests to withdraw from the elections, meaning these candidates remain in the running and can participate, since they did not submit withdrawal requests within the legal timeframe over the past months. They remain in the running, and perhaps all of them want to achieve immediate and future personal and partisan goals by announcing their withdrawal, or at best want to pressure al-Kadhimi to postpone elections until the end of next year.

It is noteworthy that some of the political entities that have not withdrawn from the elections have suspended their electoral advertising because they are certain that the elections cannot proceed on time. The decisive factor on the issue of elections is whether or not the Iraqi parliament will dissolve itself on October 7, three days before the elections are scheduled to take place.

But it seems that al-Sadr’s withdrawal was not an absurd move, but rather, had political goals. This can be clearly understood through al-Sadr's statement last August when he declared his return to the election race. According to him, “Our participation in the electoral process has become an acceptable matter and we will enter these elections with vigor and determination to save Iraq from occupation, corruption, dependency and normalization.”

There are also significant barriers in terms of Iraqis’ sense of representation. The absence of real political representation for some of the oppressed or downtrodden regions is also a fundamental barrier. This has generated a conviction among many groups that elections are a tool for personal wealth, partisan predation, and political bullying, rather than a tool for oversight of the government’s performance and mature parliamentary work aiming to realize the hopes and aspirations of the people and the growth and development of the country. This conviction caused a clear reluctance to participate in past elections, and this aversion is likewise expected in the next elections.

How can elections be expected with this popular anger, represented by the Tishreen demonstrations and popular campaigns calling for the prosecution of criminals and achievement of social justice? These just demands have not been answered by any government so far, including al-Kadhimi’s. And how can elections be held in areas where people’s sons have been accused of being terrorists, many of them pursued under false pretexts and accusations? Added to these issues, the government has decided not to involve Iraqis displaced outside the country in the vote—clearly emphasizing that there is no real parliamentary representation for all segments of Iraqi society, especially displaced Iraqis in neighboring countries and continents.

The growth of terrorism is also a clear indication of the lack of suitable ground for the elections. This applies to all of Iraq’s western, eastern, and northern cities—except for the Kurdistan region—and most southern cities, which are witnessing the return of terrorist groups to abuse many cities, including Diyala, Saladin, Mosul, the Baghdad belt areas, and others.

Given the state of elections in Iraq—from the electoral process and the spread of political money, terrorism, and intimidation—Iraqis cannot expect free and transparent elections. If transparent elections were to actually occur, Iraq would need a transitional period, during which a fair electoral process could be arranged with real international supervision that could exert more pressure on the government of Baghdad to prevent interference of armed militias aiming to alter the will of Iraqi voters. There is also the need to increase the number of international observers and activate electronic monitoring. International supervision should also include ensuring the security of ballot boxes and speeding up the announcement of the results within 24 hours, as promised by Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s government.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the election law, which was approved by the Iraqi Council of Representatives and ratified by President Barham Salih in November 2020, did not manage to restrain the interference of the armed militia in the political and electoral scenes. Consequently, the armed militias will continue to control the legislative process within the parliament. Undoubtedly, the dominance of the armed militias will reflect on all sovereign decisions pertinent to both internal and external issues and will support the continuation of the state of non-state (ladaula) in Iraq for four new years.

It is only after the many factors preventing transparency are addressed that elections can produce a people’s parliament free of murderers and criminals, in which the largest bloc is the one that forms a government representing all Iraqis and aims to build a state of citizenship. At that time, we can lay the first brick to build a happy Iraq. It likewise remains to be seen whether the major powers, first and foremost the United States, will do their utmost to help Iraqis realize this great dream, or whether we Iraqis will continue to revolve in this cycle full of intimidation and fear, based on the policy of a non-state state.