- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Iraqi Popular Opinion of Kadhimi Is Weakly Supportive, but Could Tip Either Way

While much ink has been spilled over whether Iran and the United States have a favorable or unfavorable opinion of new Iraqi Prime Minster Mustafa al-Kadhimi, the most important opinion is that of Iraqis. It is particularly important what Iraq’s Shia population thinks of their new prime minister, as they are the largest community in Iraq and have the most power over the direction of the country.

While Kadhimi passed his first difficult test by successfully obtaining the approval of his cabinet members from Iraq’s parliamentary blocs on June 6, the country’s myriad challenges require the difficult balance of effective action with limited funds.

The next key step is to win the hearts and minds of the Iraqi public. In particular, Kadhimi must reach those who have been protesting in Shia areas since October 2019 who pressured his predecessor Adil Abdul-Mahdi to resign. While COVID-19 has slowed down the momentum of these unprecedented protests, the demonstration sites have not emptied, and their discontent continues unabated.

Though the battle for the hearts and minds of young Shia is crucial for Kadhimi’s future as prime minister, winning over this group will likely prove very difficult given Iraq’s staggering economic crisis. Iraq’s dire economic situation—an initial spark of the protests—is worsening due to two major factors: the ongoing lockdown ordered because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crushing blow to revenues and employment due to the sharp drop in oil prices. As oil revenues account for 90-95% of Iraqi national income, the oil price crash—precipitated by the global economic slowdown and the Saudi Arabia-Russia oil price competition—is a disaster for Iraq’s economy.

This crisis has left Kadhimi’s government with extremely limited options to placate the young Shia protesters who are demanding jobs, an improvement in public services, and an end to corruption. The prime minister is trapped in a catch-22 as if he wants to get the Iraqi economy back on solid footing for growth, he will have to implement some very unpopular policies, such as slashing jobs and wages to overcome the problem of Iraq’s bloated and unproductive public sector.

Yet the most recent numbers from a nationwide telephone poll conducted by Al Mustakilla Research Group in Iraq suggest that Kadhimi is in a good place to weather the economic and political storm if he can prove himself to the Iraqi public. The poll—which took place over a week (June 6-11) with 1,036 respondents—demonstrated that Iraqis appear willing to be won over.

On the one hand, the poll showed that although 49% of Iraqis are satisfied with the selection of Kadhimi as prime minister, only 40% of Shia approved of his selection. However, this unhappiness with the choice of Kadhimi from Shia has more to do with the process behind his selection, which is typically the result of backroom deals between political blocs to settle on a consensus candidate. In particular, the Shia are fed up with Shia political bosses that they see working for themselves and not the people, which may be reflected in these polling results.

Contributing to this interpretation are Iraqis’ views of the man himself. The survey results show that 64% of Iraqis voiced a favorable opinion of Kadhimi. This percentage is much higher than those indicated for his predecessor, Adil Abdul-Mahdi, who had a mere 36% favorability rating one month after his appointment in 2018. More significant for Kadhimi is that 60% of Shia have a favorable attitude toward him.

Moreover, almost 60% of all Iraqis polled stated that they approved of Kadhimi’s performance as prime minister. Again, this majority is significantly higher than the approval rating for Abdul-Mahdi as prime minister from almost the same period in 2018 (46%). Crucially, 60% of Shia approve of Kadhimi’s performance. This base of approval is key to his political survival.

On September 1, 1922, the British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill, when writing to his prime minister, described ruling Iraq as akin to sitting on a volcano. This imagery has proved apt for Iraq’s successive prime ministers, and it is no different for Kadhimi, who faces a very angry electorate whose demand for reform has increasingly shaken up Iraqi politics. If the anger in Iraq is not managed adeptly, it will not only have negative consequences for Iraq’s political system but also for the region’s security. An Iraq that descends into political chaos is a threat to its neighbors, as has been evidenced before.

Given these challenges, the polling data suggests current widespread political support but not necessarily an unchallenged way forward. Three important factors must also be highlighted to better understand the weight of Iraqis’ attitudes towards Kadhimi. First, Kadhimi replaced a distinctly unpopular predecessor after his removal due to the protests. As Abdul-Mahdi was one of the most hated prime minsters in post-2003 Iraq, it is to be expected that the juxtaposition will help Kadhimi by comparison. It must also be acknowledged that Kadhimi is also enjoying a political honeymoon, which most leaders enjoy during their first few months in office.

Moreover, closer analysis of these polls suggests that many Iraqis are relatively ambivalent in their support for Kadhimi. Many survey respondents ranked their favorability or lack of favorability toward Khadhimi toward the middle of the response range, suggesting that many Iraqis have either weakly favorable or unfavorable attitudes towards him. Thus, Kadhimi has neither very ardent support nor very strong opposition, suggesting that his popularity could tip either way depending on the course of events. For Kadhimi, it is very likely that his ability to deliver on his promises will either make or break him politically. As for now, he has no solid, societal base of unwavering support.

Kadhimi will most likely be judged by the Iraqi and particularly the Shia public on how he delivers on four issues. First, his ability to make tangible improvements in the fight against corruption will be closely watched. Sending some corrupt major political bosses to stand trial would be proof of this. Second, publicly identifying some of those who were in charge of killing young, peaceful protesters is a major demand of the Shia public. Third, he is expected to impose the formal government institutions’ control over the actual running of the state of Iraq. Right now, informal actors are strong and controlling many important institutions. These actors are viewed as the arms of the “deep state” in Iraq. Militias, corruption networks, and political machines are among the most important informal actors that are deeply reviled by much of the public. Finally, he will be judged by the public for showing actual progress toward an early, fair election as he promised in his cabinet agenda.

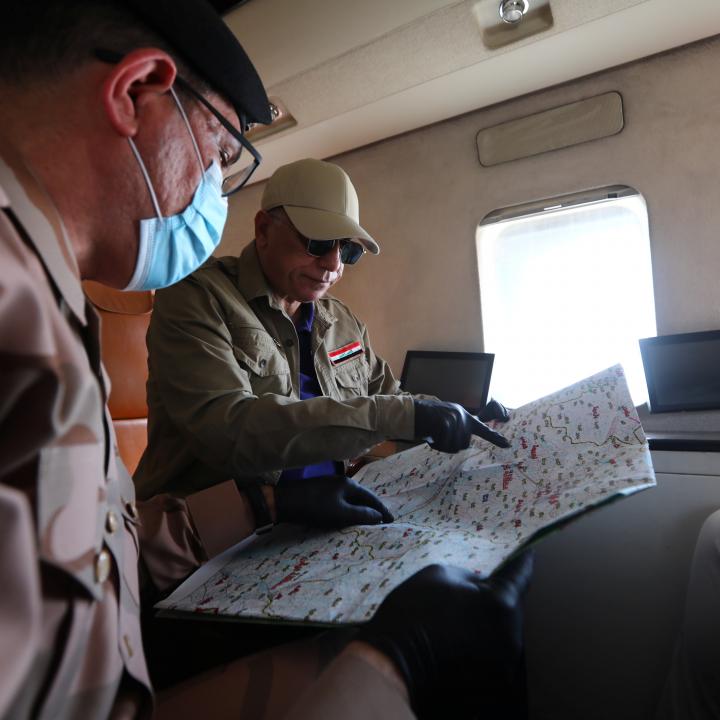

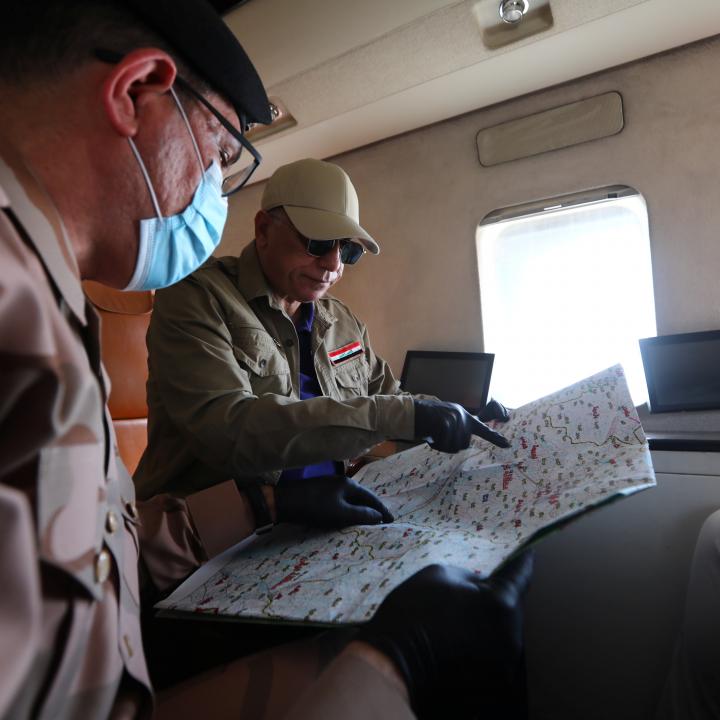

The past month has tested Kadhimi in significant ways. Two events in particular have undermined Kadhimi’s ability to show progress on reigning in the Shia militias. On June 26, Kadhimi ordered the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Service (CTS) to arrest militants of Kataib Hezbollah who were, according to intelligence, planning to strike U.S. forces. While the action was applauded by many Iraqis who have grown concerned about the power of such militias to act as a state within a state, thirteen of the militants were released just three days later, with just one remaining in custody. The release was prompted by Kataib Hezbollah and other militias marching into the Green Zone in Baghdad and threatening violence against the CTS unless the detainees were released. For Kadhimi, it was a stark reminder of how limited the power of the Iraqi formal state is in relation to that of the Iran-linked Shia militias.

The next serious blow to Kadhimi’s ability to challenge the militias came on July 6, with the murder of Husham al Hashemi, a very prominent and well-respected civilian security advisor to the Iraqi government. Hashemi, a leading expert on Iraqi jihadis and militias, had angered Iran-leaning Shia militias for his research work and commentary on those groups. The murder was also likely intended to be a signal to Kadhimi to back off his attempts to reduce the power of the Shia militias. There is now tremendous pressure on Kadhimi to bring Hashimi’s killers to justice, but trying to do so may result in a show-down that he might not be able to win.

Kadhimi is facing a formidable set of challenges in Iraq. There are high expectations for him to achieve positive change in Iraq, but he has limited power to achieve those changes. Failure to deliver on his promises to reign in the militias, to deliver a rising standard of living, to reduce corruption, and to manage a free and fair national election could see Kadhimi turn into yet another Iraqi prime minister who gets destroyed by the Iraqi “volcano.”