- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Iraq’s Missed Development Pathway Highlights the Necessity of Unpopular Economic Reforms

Institutional limitations, fiscal challenges, endemic corruption, and governance shortcomings present formidable barriers to developmental pursuits.

Last month, a consortium of MPs, government officials, and representatives from private enterprises and NGOs announced the Baghdad Alliance to Support the Private Sector. This initiative, similar to many previous unfulfilled governments’ development strategies and plans, aims to foster private sector development, hoping to accelerate sustainable economic growth in Iraq. While these objectives resonate with the ambitions of PM Mohammed Shia Al-Sudani’s cabinet programs focusing on bolstering private enterprise and attracting foreign direct investment, they will remain unrealistic unless they correspond with a set of comprehensive fiscal and regulatory reforms.

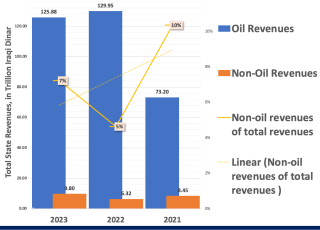

Historically, this is not first-time private sector development has gained political traction. It has played a key role in all the strategies and plans of Federal Government of Iraq (FGI) since 2006 such as Natiuonal Development Strategies (2005 – 2007 and 2007 – 2010), National Development Plans (2010, 2013 – 2017 and 2018 – 2022). Numerous international organizations, donor countries, and local academic and NGO entities have extended their support to the FGI to pursue this developmental path. It also underpins the majority of strategic plans and policies aiming to diversify Iraq's economy and reduce its dependence on crude oil exports, which is still 93% of state revenues in 2023. Likewise, the prioritization is augmented by the introduction of the Iraq-Turkey Development Road project, aiming to allure foreign capital, investors, and expertise.

Given Iraq's rentier economy and inherent structural imbalances, the private sector is weak, underdeveloped, and heavily reliant on state-funded projects. Yet, institutional limitations, fiscal challenges, endemic corruption, and governance shortcomings present formidable barriers to such developmental pursuits.

What Impedes the Development Dream?

From a fiscal standpoint, PM Sudani’s government is continuing the prevalent post-2003 fiscal trend, characterized by a rentier approach where the lion's share of state resources–derived from crude oil exports–is allocated to salaries. This leaves a meager portion for infrastructure and development investments. Most of these salaries are in economically unproductive sectors such as the military, security, religious endowment institutions, and numerous state-owned enterprises that are out of business but still takes part of the payroll funds as a way to mitigate rising unemployment.

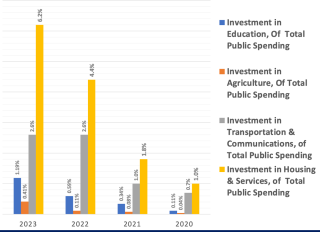

In many cases, public funds are essentially deployed to secure constituents’ loyalty for the ruling class at the expense of infrastructure and service institutions. The government’s 2023 expenditure pattern mirrors this fiscal trend. Investment expenditures in key job-creating sectors, where the potential for private sector development exist, remain modest as demonstrated by the following figure.

Figure 1 Investment expenditures in key non-oil sectors

Data sourced from Iraq’s Ministry of Finance website of Iraq’s Ministry of Finance

Figure 1 shows how investment spending across key sectors in the best financial year, 2023, constitutes less than 14% of total expenditures. It is highlighting how the PM Sudani’s government so far perpetuates rather than deviates from the post-2003 fiscal trend.

Another way to assess the FGI’s commitments to its developmental strategies is by examining public investments in sectors with potential for job creation, human resource development, and improving a business enabling environment. An evaluation of the Iraqi government's expenditure in non-oil industries reveals a glaring shortfall in commitment to its developmental strategies and objectives.

The data is taken from the formal website of Iraq’s Ministry of Finance

Public spending in non-oil industries came out to less than 1% in 2023. Although these industries should ideally be led by private firms, state-owned enterprises playing a complementary role by providing raw materials and other support for private sector activities at least for a while until they would be privatized. The above figures indicate that the current government has curtailed investment in non-oil industries, contradicting its stated objectives. During Iraq's boom years, characterized by high international oil prices and resultant windfalls, there was ample scope for increased public investment. However, most of this investment in 2023 was directed towards the oil sector, which affords very limited potential for job creation. Investing in non-oil industries is what was supposed to take the largest bulk of the public-investment allocations in 2023 as a way to catalyze sustainable growth according to the cabinet program as well as various FGI’s development strategies and plans.

The necessary policy reforms present formidable political challenges; myopic approaches of the rising populist trend among the ruling class is just one of them. For instance, in response to the 2020 economic shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and oil price collapse, the preceding government tried to levy personal income taxes on civil servants' and pensioners' salaries to augment non-oil state revenues. The taxation required amending the Law of Income Tax No. 113 (1982) and Coalition Provisional Authority’s Order 49 (2004), but it encountered intense opposition inside parliament on a populist basis, thwarting its implementation. Consequently, Iraq's non-oil revenues have dwindled, and its dependency on oil revenues surged to over 93% in 2023. The subsequent figures depict the decline in non-oil revenues from 10% in 2021 to 7% in 2023.

The date is taken from the formal website of Iraq’s Ministry of Finance

Given the prevailing fiscal and economic challenges, private sector development remains a Herculean task. Numerous policy endeavors and strategic initiatives of past Iraqi governments aimed at this objective have failed to yield tangible results. PM Sudani’s government faces similar impediments as its predecessors. As evidenced by the fiscal policy and the three-year budget law, there's inadequate allocation for investments to pursue developmental objectives. Due to the rising populism, the ruling class and their subsequent governments ignored national developmental strategies and plans in pursue of short-term electoral gains.

Furthermore, despite benefiting from oil windfalls due to increasing oil prices in recent years, corruption, inter-elite conflicts, and bureaucratic obstacles have hindered the execution of planned investment spending outlined in the 2023 budget law. The government disbursed approximately IQD 24 trillion (48%) of the planned IQD 50 billion for investment and developmental spending. Similarly, it disbursed 60% of the total planned spending, amounting to IQD 118 trillion out of IQD 198 trillion. These figures underscore the government's lack of commitment to its developmental goals.

The current Iraqi government is unlikely to exceed these challenges without adopting a smarter strategic approach. Altering this deep-rooted fiscal policy is as challenging for this government as it was for its predecessors. Expenditures on salaries, pensions, and subsidies for public sector employees in 2023 exceeded IQD 72 trillion, accounting for 61% of total government expenditures. The bloated public payroll is anticipated to grow further as the government intends to recruit one million new employees to address national unemployment.

Generally, business environment in Iraq remains poor, hindering the growth of the private sector and significantly deterring foreign direct investment. For instance, Iraq's ranking in the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index is 154th out of 180 countries, placing it among the most corrupt nations. Furthermore, the country still lacks the necessary security measures and political stability to attract investors. Earlier this month, the nation's largest gas-producing field, Khor Mor, was targeted by a suicide drone for the 9th time over the past 3 years. This attack underscores the fragile stability that Prime Minister Sudani's government and KRG have provided, contrary to the image portrayed by certain PR campaigns. Moreover, persistent challenges such as lack of finance, bureaucratic obstacles, and inadequate regulatory environment remain largely unaddressed.

Breaking The Vicious Circle of Iraq’s Fiscal Policy

The influx of oil revenues serves as both illness and cure to Iraq's economic conundrum. When oil prices cyclically decline, Iraq faces predictable yet severe economic shocks. Over the past decade, oil revenues constituted 99% of Iraq’s exports, 85% of government budgets, and 42% of GDP. At current production and export levels, a $1 decrease in the international oil price translates to a $1.23 billion annual revenue loss for Iraq. Consequently, stimulating and sustaining economic growth–the principal drivers of development–largely remains beyond Iraqi control, dictated by the volatility of oil prices in international markets. Beyond the fiscal instability induced by oil price fluctuations, the general abundance of oil revenues has shaped Iraq’s economic landscape, influenced the behavior of its ruling class, and exposed the nation to the classic symptoms of Dutch Disease.

To alter this trajectory, the Iraqi government needs to implement a series of fiscal reforms that can support the push towards economic development. Revitalizing industries, agricultura, tourism, and transportation sectors that ultimately lead to economic diversification will bolster resilience against the shocks of cyclical oil price fluctuations and pave the way for sustained growth. Under these conditions, private sector development can emerge as a pragmatic aspiration and a remedy for Iraq’s structural imbalances.

Robust physical infrastructure is also a necessary investment and one of the pre-conditions for any developmental success—requiring the repair or establishments of roads, bridges, power plants, and grids that can support a growing private economy. Given Iraq’s scarce resources, the desired investments will remain elusive unless state revenues are increased or fiscal policies are recalibrated to reduce current expenditures and allocate more towards infrastructure investments.

One way to promote private sector development and ultimately circumvent the current fiscal constraints on Iraq’s development goals is designing public-private partnership (PPP). This requires engaging both domestic and international enterprises and investors. However, evidence from developing economies suggests that while PPP might underpin private sector involvement, it often yields mixed results in term of development outcomes. Effective PPPs necessitate a robust regulatory framework, adherence to the rule of law, and strict public accountability. None of these conditions is properly holding in Iraq.

Another imperative is devising a strategy to navigate the political complexities associated with Iraq's consensual government formation model, Muhasasa. This power-sharing arrangement allocates key governmental positions among political parties representing Arab Shia, Arab Sunnis, and Kurds based on electoral majority. Moreover, it partitions rents derived predominantly from public funds and contracts among these political parties. This arrangement has created a unique political economy wherein each ruling party distributes state resources, employment opportunities, and services-contracts to consolidate loyalty within their respective constituencies. This has contributed significantly to the bloated public payroll, overlooked investment initiatives, and subsequent fiscal difficulties. Just in 2023, FGI added more than 800 thousand people on the public payroll, either hiring them in the already bloated public sector or adding them to the list of recipients of social benefits. Formulating a strategy to mitigate the costs associated with political parties' rents, extortions, and corruption will result in substantial resource savings for Iraq.

Furthermore, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) offers another way to achieve some better development outcomes. To date, Iraq has predominantly attracted foreign firms for service-oriented projects within the electricity and oil & gas sectors. The engagement of foreign entities often translates to the outsourcing of specific services to global corporations such as GE, Siemens, and Chinese firms. Because FDIs have primarily targeted the oil and gas sector, this opportunity has failed to reach to the job creating non-oil private sector.

Finally, reforming Iraq’s financial sector would certainly improve the business enabling environment, creating many new opportunities for young entrepreneurs and market makers. It would help formalize informal economic activities that constitute largest segment of Iraq’s private sector. The reform steps would also allow the country to further its development goals.

The recent pressures of U.S. Treasury on Iraq’s banks towards compliance to anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) measures are yielding some positive results. The financial inclusion has increased dramatically via activation of electronic payment in governmental and private institutions in addition to reforming mechanisms for financing foreign trade since December 2022. The number of accounts in Iraqi banks increased by 14% just in the first three quarters of 2023 to become 10.02 million accounts, while it was 8.79 million accounts at the end of 2022, when the U.S. Treasury’s pressures started.

The necessary reforms needed to underpin the economic shift championed by Sudani should lead to a dramatic shift towards prioritizing infrastructure investments over recurrent expenditures, reversing the fiscal trend to which all the post-2003 Iraqi governments, including the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), have adhered. While such a process is neither easy nor welcomed politically regardless of how much it is needed to achieve better developmental outcomes, and has served as one of the major stumbling blocks to previous attempts, it will have to be addressed before Iraq can achieve its “Development Dream.”