- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

“The Jungle:” A visit to a French Refugee Camp

April 14, 2016

The journey from London to the French coastal city of Calais was quick and comfortable . I nearly forgot I was traveling between two different countries until I was greeted by high fences and endless spirals of barbed wire, which marked the boundaries of the refugee camp. Police vans were everywhere and armed police forces patrolled the entire perimeter of the fence. Tensions stemming from a sense of crisis and emergency were overwhelmingly palpable in the camp. Just a few hours from London, ‘the Jungle’ seemed like another world.

A few of my colleagues and I travelled to Calais’ refugee camp, now widely known as “the jungle,” to assess the situation inside the camp. We also hoped to interview Syrian refugees there on their views regarding peace in Syria as part of the virtual campaign message4peace. This online platform, in coordination with iguacu, was designed to send a message for peace to Geneva peace talks, and to raise awareness of the continuing challenges facing Syrians within and outside of Syria. However, the reality of the camp was a jarringly stark reminder of what these refugees’ daily lives are like.

Arriving near the entrance, we parked our car next to the famous Banksy mural of Steve Jobs and entered the camp by foot. The camp was still smouldering from clashes with the police, a result of the French authorities’ attempts to dismantle the camp. Tents that remained standing were nevertheless in a pitiful state.

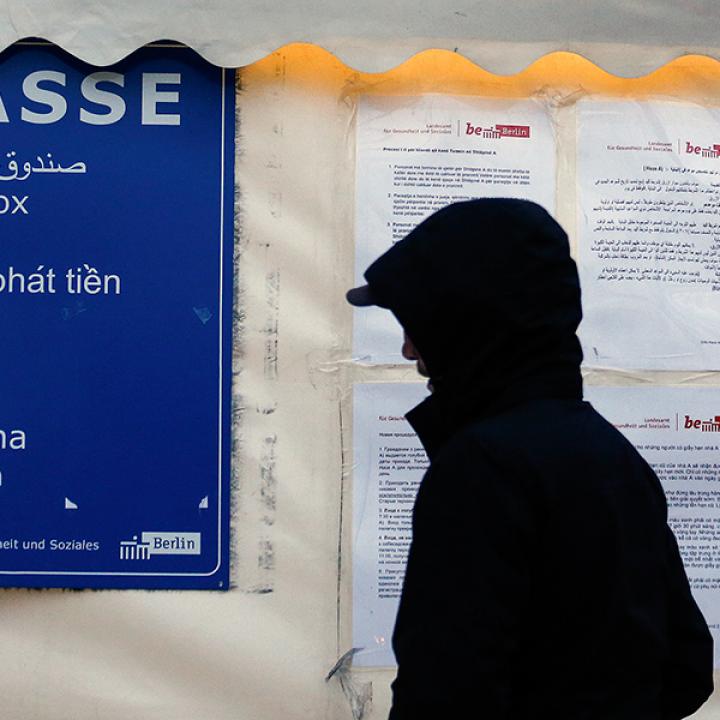

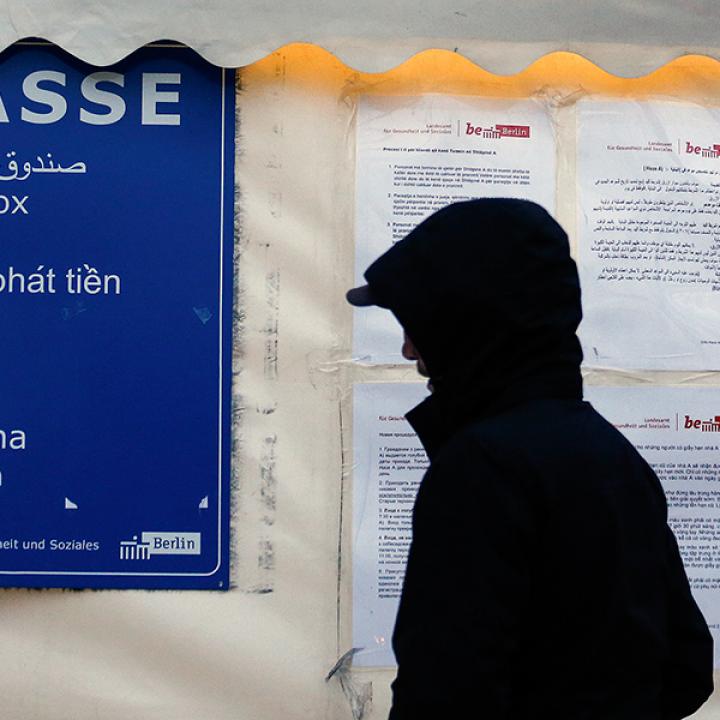

The inhabitants of this burnt and disjointed temporary housing formed a multiethnic community, with little in common except their shared status as survivors of conflict and displacement. Afghans, Somalis, Iraqis, Sudanese, Syrians, Eritreans, and others displayed their identities through shabby flags in front of tents and the diversity of languages written on signs covering tarpaulin walls. A structure that appeared to be a church and tents operating as mosques for a variety of Muslim religious communities presented another avenue for maintaining identity. These attempts to create familiarity contrasted with the inescapable dirt and awful sanitation system. Sewage water ran in exposed pipes, forming canals and large puddles throughout the campgrounds. The living conditions were truly deplorable, unfit for human habitation.

The Jungle’s 300 Syrian refugees live on the Jungle’s outer peripheries, and I had the chance to speak to a number of them about their lives, dreams, and fears. They make up a relatively small number of the Calais jungle; the majority arrived in an attempt to connect to their relatives in the United Kingdom. Most of those to whom I talked lived in the southern Syrian region of Dar’a, where the first demonstrations and clashes against the government began five years ago. Those I spoke with told me about the early unrest and crackdowns on protesters, as well as their personal reasons for fleeing. One had been detained three times while in Syria and subjected to torture. Another refugee was shot in the foot before leaving the country, and a third was hit by shrapnel from a road bomb. Most were in their twenties, full of life and hope despite their current unspeakable living conditions. They hope to ultimately lead peaceful lives with their families, far from the atrocities of war. Somehow still hospitable, they insisted that we have tea or coffee in their flimsy tents. We humbly declined, not wishing to add the burden of guests to their hardship.

Despite the Syrians’ impressive optimism regarding the future, fear was the most common theme during our discussions. These refugees felt demonised and unwanted. They were scared. Even in France, many were afraid to disclose their real names, worried that someone might hurt their families in Syria or Turkey in response.

Some of them kindly accepted to write a message4peace to contribute to the campaign. These messages were incredibly touching, and they overwhelmingly focused on the people who remained in Syria. None of the refugees mentioned any concerns for their own situation. Most wrote that peace is dearly needed to stop the drain of people from their country and its destruction, and that they eventually hope to return.

Visiting the camp brought out in all of us sentiments of both solidarity and guilt. It was so easy for our group to exit the camp and travel back to London; yet those we met are trapped in misery, facing an arduous journey to escape from the camp and begin life in England. But our disparate circumstances are only due to luck and destiny. Those people happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when the war erupted. This tragedy could have happened to any of us. As a Syrian who was in London when the unrest in Syria began, I feel this sense of fate and cruelty particularly acutely.

As we were filming the recently destroyed and still smoking area of the camp, a teenager nearly drove his bike into us, stopping inches away in an attempt to intimidate us. He then asked our cameraman why he was filming. We calmly answered that we wanted to raise awareness about the situation there. Without saying a word, he left. It was a quick encounter, and he didn’t have much to say. Perhaps he was hurt and angered by the fact that people visit the camp to take pictures of the camp inhabitants’ misery. And perhaps he later realised that the world should never stop being exposed to what is happening in Calais. He left and we kept murmuring to ourselves: “This should not be happening in France, or anywhere in the world.”

Sinan al-Hawat is the senior researcher on Syria and Iraq at iguacu. He holds an MSc in Development Management from the London School of Economics and Political Science. Al-Hawat has published a number of articles on the Syrian crisis. This item was originally published on the Fikra website.

Fikra Forum