- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Kurdistan in China: Are the Iraqi Kurds Interested in a Relationship?

China’s presence in Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan is expanding rapidly against a backdrop of China’s growing presence across the Middle East.

The era of China’s limited involvement in the region is a thing of the past; China’s ties to the region solidified during the COVID pandemic as China supplied countries with vaccines and medical supplies, and as regional officials and publics expressed increasing concerns about a U.S. withdrawal from the region.

This trend manifested in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) as well, where China has expanded its relationship beyond the traditional oil market. China exported medical supplies to the KRI, China’s Consul General and the KRG Health minister held a joint press conference Erbil, Chinese companies signed contracts to build schools across Iraq, and Chinese language instruction has become increasingly common in Erbil. China is also currently competing with two regional powers—Iran and Turkey—to flood the local Kurdish market with goods. Chinese companies are becoming increasingly visible and outpacing more established ones, namely western firms, by gaining contracts in various areas, especially in the oil sector.

An adviser to an international oil company once explained to the authors that Chinese companies are winning bids more easily than Western companies in Iraq because they are state owned enterprises that have the flexibility to prioritize energy security over profits. Meanwhile, Western companies constrained by regulations are less willing to conduct business in a risky, corrupt environment. In recent years, major international oil companies have become less interested in investing in Iraq and have abandoned the country entirely. The Iraqi government is concerned, but because of nature of Iraqi oil contracts (service contracts) and oil nationalism, the country is unable to prevent these companies form leaving the country.

China-KRI relations

Similar to the rest of Iraq, the Chinese relationship with the Kurdistan region is diverse. Just recently, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) Ministry of Agriculture and PowerChina International Group Ltd signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to construct four dams in the region. In an interview, KRG Minister of Agriculture and Water Begard Talabani said that the Chinese company offered a better deal that would cost the KRG less. In 2020, China signed a $5 billion residential and leisure development in Erbil called Happy City.

Yet while China is expanding in every area within the KRI, the relationship remains notably one-sided. China opened its general consulate in Erbil in 2014, when the KRG was fighting ISIS. For the Chinese, it was an opportunity to show solidarity. In contrast, a U.S. State Department official characterized it China capitalizing on the KRI’s weakness as it struggled to survive. Regardless of the motive, bilateral relations with China are important to KRG diplomatic elites, who understand the significance of China's permanent membership on the UN Security Council. Through private conversations and interviews, we learned that China was the last permanent UNSC member to open a consulate in Erbil, and had done so at the insistence of senior KRG diplomats.

Yet seven years after the opening of the Chinese General Consulate in Erbil, the KRG has yet to open an office in Beijing. Decision-making elites explain this discrepancy in different ways. In a recent, private conversation we held with former Iraqi ambassador to China Mohammad Sabir, the former ambassador was very enthusiastic about China and the country’s culture. Moreover, Sabir explained that following a Kurdish request to Beijing for political representation in 2007, Chinese officials told Iraqi president Jalal Talabani, a long-time self-proclaimed Maoist, that the KRG could only open a commercial office registered under a company name.

China was not willing to open the office, but nevertheless wanted a channel to communicate with Iraqi Kurdistan—a relationship without recognition. China’s reservations regarding official diplomatic ties with the KRI stemmed from concerns about the repercussions of recognizing a regional government within a nation state.

For one, China worries that recognition of the KRI could empower Chinese provinces to demand a role in Chinese foreign policy. The central government in Beijing monopolizes every aspect of political, economic, and social activities—leaving provincial governments with no say in foreign policymaking—and China would not want to make a foreign policy decision that jeopardizes this domestic arrangement. Additionally, the CCP’s positions on Taiwan and Hong Kong and its strong rejection of separatism makes it leery of establishing ties with a sub-state entity. And while China claims not to politicize its leverage, we found through our interviews that it prevented the KRG from building ties to Taiwan.

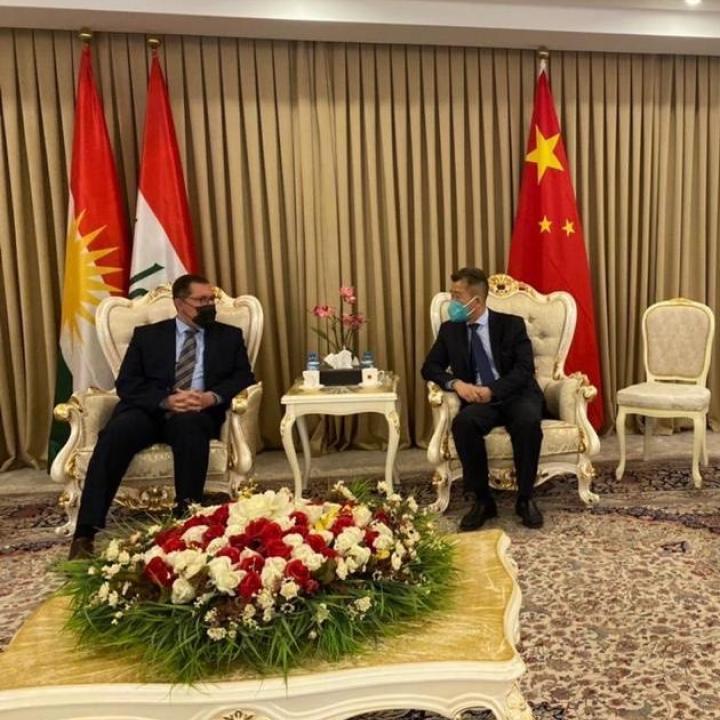

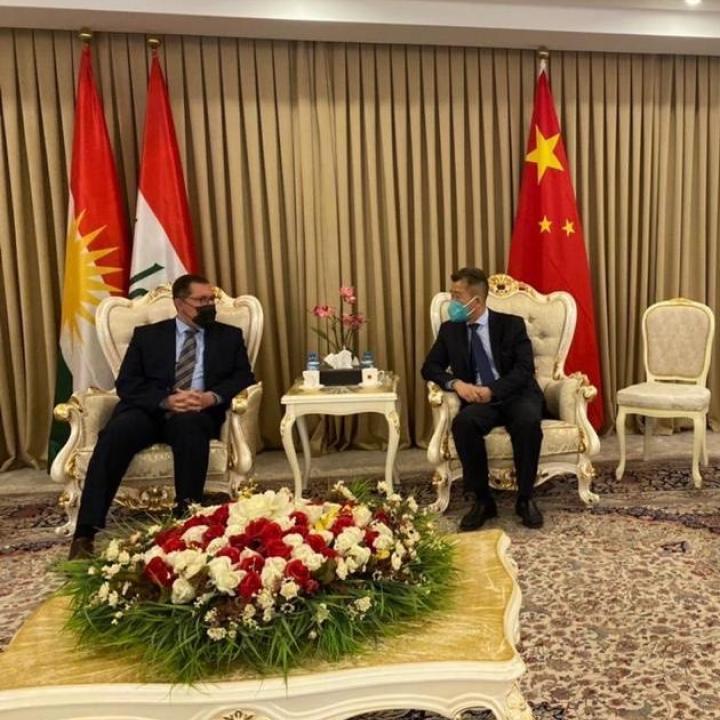

However, Chinese diplomats present an entirely different story when asked about the discrepancy. In 2021, Chinese Consul General to Erbil Ni Ruchi said the KRG had not opened an office in Beijing because the KRG had not made such a request. Former ambassador Sabir said this was diplomatic talk rather than the actuality.

Falah Mustafa, senior advisor to the KRI president, said that the KRG had plans to increase its number of representations globally, including in East Asia, but that this initiative faced numerous challenges and setbacks. Mustafa explained that Baghdad’s cut of Kurdistan’s share of the national budget, the ISIS incursion, an influx of refugees and IDPs, and decreases in global oil prices collectively prevented the KRG from submitting a request to open an official office in Beijing. Other senior KRG diplomats corroborated this explanation, saying that they did not submit a request to Beijing due to the funds and resources required to open the mission at a time of extreme austerity in the KRI.

According to China-Middle East scholar Yitzhak Shichor, "one of the basic components of post-Mao China’s policy, domestic and international, is opposition to separatism. These rules also apply to the Kurds." However, recent events are providing China with more room to maneuver when it comes to an official KRG presence in Beijing. Relying on Iraq’s constitutional recognition of the Kurdish-ruled entity and the international reaction to the 2017 referendum, China could quell its prior concerns about the potentially harmful ramifications of KRG representation in Beijing.

While China still seems to be leary of official relations, the Chinese consulate in Erbil is attempting to strengthen its relationship with the KRI through unofficial channels by focusing on ties with political parties rather than with the government. The Chinese government is specifically attempting to attract the cadres of the prominent Kurdish political parties—the, PUK, KDP, and the Gorran party. According to interviews with senior party officials, each year two delegations are invited to China: one of senior party members and the other of mid-level party officials.

Even so, there is growing skepticism about China's presence and expansion in Kurdistan and Iraq. While both Iraq and Kurdistan are attracted to Chinese megaprojects, and many Iraqi political forces prefer development discourse over democracy, rising global tensions between China and the United States concern local leaders.

In this context, the failure to open the KRG representation in Beijing could be attributed to mutual disinterest on the part of the Chinese and the KRI, each for their own reasons. Kurds cannot sacrifice security for economic development, especially at a time when other regional powers are preparing to intervene and expand in Iraq.