- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Kuwaitis Dislike Trump, but Favor the United States over Iran Despite Sectarian Mix

Of all the Gulf monarchies, Kuwait’s actively elected parliament and opposition groups distinguish it as the one where public opinion matters most. A rare recent poll shows that much of the country’s public lines up with its government on many (though not all) key issues, despite the country’s mixed Sunni/Shia population and widespread popular concern regarding corruption.

Overall, attitudes within Kuwait have changed very little in the past five years when compared with previous polls. These findings suggest continued stability in both foreign and domestic policy—but with surprising, recent receptivity to a role in Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking.

Among Kuwait’s roughly 1.5 million citizens, U.S. President Trump gets an approval rating of just 5 percent—exactly on par with Russian President Putin, if that is any consolation. In sharp contrast, Turkish President Erdogan enjoys favorable ratings from 64 percent of Kuwaitis. Chinese President Xi comes out almost as well, with 49 percent approval.

Yet when asked if their country needs good relations with the United States, a much larger proportion of Kuwaitis answer in the affirmative: 49 percent, including 27 percent who consider those relations “very important.” By comparison, a mere 7 percent say good ties with Iran are “very important,” with barely another 10 percent describing such ties “somewhat” so. This total, however, masks a stark sectarian divide: among Kuwait’s nearly one-third Shia minority, fully 52 percent say good relations with Iran should be valued.

At the same time, Iran’s regional allies get largely negative ratings even from Kuwait’s Shia. Lebanon’s Hezbollah rates only 11 percent positive among its Kuwaiti coreligionists. Yemen’s Houthis fare somewhat better, although just approximately one-quarter of Kuwaiti Shia give them favorable reviews. The country’s Sunni majority overwhelmingly disapproves both of these Iranian-backed foreign movements.

When asked about their priorities for American policy in the region, Kuwait’s general public divides almost evenly among a wide variety of issues: counter-terrorism, containing Iran, the Yemen civil war, or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Significantly, however, only 15 percent at most want the United States to “reduce its interference in the region.” This low proportion is approximately in line with findings from seven other Arab countries polled in the past two years, notwithstanding wide popular disapproval of current U.S. policy as a whole.

In another unexpectedly encouraging finding, a solid majority of Kuwaitis—63 percent—agree with the latest U.S. suggestion that “Arab states should play a new role in Palestinian-Israeli peace talks, offering both sides incentives to take more moderate positions.” This figure, too, is similar to those found in polls of other Arab states, regardless of Kuwait’s more reticent official policy and reputation as the most anti-Israeli of the GCC states today.

A few cautionary notes regarding this connection, however, come from the results of two related questions. Only 14 percent of Kuwaitis, the lowest among all eight countries recently polled, say that Arab states should already “work with Israel on issues like technology, counter-terrorism, and containing Iran,” even before any agreement on the Palestinian problem. And 52 percent of the Kuwaiti public, among the highest proportions in the region, voice a favorable opinion of Hamas—the Palestinian Islamist movement that rejects any peace deal with Israel altogether.

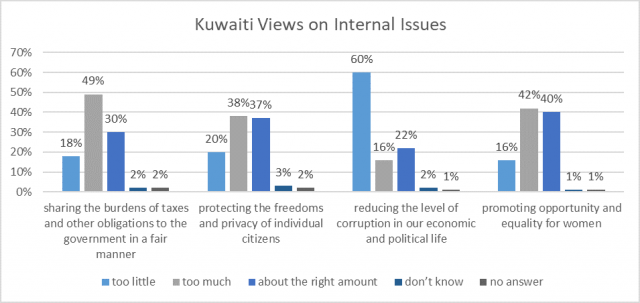

On internal affairs, there is one issue where a clear majority in Kuwait, as in all the other countries surveyed think their government is doing “too little”: combating corruption. On other issues—from women’s rights, to individual privacy, to sharing the burden of taxes and other civic obligations—attitudes are much more mixed, with 30-40 percent saying government efforts are “about right.” Similarly, 36 percent of Kuwaitis agree that “we should listen to those among us who are trying to interpret Islam in a more moderate, tolerant, and modern direction.” Sixty percent disagree, although just one-quarter say they are “strongly” opposed.

More broadly, 60 percent of Kuwaitis say that “right now, internal political and economic reform is more important for our country than any foreign policy issue.” While this is a majority, it is a smaller one than in any of the other seven Arab countries polled in the past two years. Also supportive of a suggestion of Kuwait’s domestic harmony is that on all of these issues, there exist only modest differences of opinion between the country’s Sunni majority and Shia minority. In this sense, Kuwaiti society continues to represent an unusually clear-cut case of consensual sects.

Nevertheless, there is a very wide sectarian divergence on one important internal issue. When asked for their opinion of the Muslim Brotherhood, a Sunni fundamentalist political movement tolerated in Kuwait but outlawed in some other Arab states, nearly half of Kuwaiti Sunnis (45 percent) report a favorable opinion. This is the highest percentage registered in any recent survey in the region.

In stark contrast, the Brotherhood gets a positive rating from just 3 percent of Kuwait’s Shia. Yet this divide probably works to the Kuwaiti government’s advantage: some of the Sunnis are allowed a relatively popular opposition voice; some of the Shia seek protection against it; and the overall majority tend to look to the government as the arbiter between the two.

Thus, in this counter-intuitive interpretation, a major social divide revealed by this survey data is precisely one of the factors behind Kuwait’s political stability.

These findings are from a reliable commercial survey conducted by a regional firm in November 2018. The survey comprised personal interviews with a representative national sample of 1,000 Kuwaiti citizens, randomly selected using standard geographic probability techniques. Comparisons are from similar surveys conducted in late 2017 and late 2018 in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon. Full methodological details, including field texts of the survey instrument, demographic breaks, sampling frames, refusals and “don’t know” response rates, and other information, are readily available from the author on request.