- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Manufacturing Extremism in Iraq: ISIS, the Sarkhi Movement, and Popular Discontent

Some reject the idea of a potential ‘ISIS-ification’ of southern Iraq, but radicalization can occur anywhere when the social tensions are sufficiently severe. Southern Iraq certainly faces this dilemma.

Over the course of two years, I conducted a study in Iraq focusing on extremism and why young Iraqis join ISIS. Along with four American scholars specialized in the psychology of terrorism, political science, and social networks, we based our work (to be published later this year) on interviews with fifty ISIS members and thousands of residents of areas that have suffered from ISIS terrorism.

During these interviews, we found that the ISIS recruitment process passes through two stages: social tension, then radicalization or “ISIS-ification.” In the first stage, the community in question goes through political, economic, and social conditions that are chronically harsh and extreme. These pressures lead to societal breakdown amid security, economic, social, and political tensions. This societal failure manifests in poverty, demonstrations, social discrimination, violence, and the degradation of community values.

It is at this stage that many begin to lose their faith in the group to which they originally belong because of its failure to provide social stability or psychological and physical security. Then comes the second stage, where a majority of “followers” are ready to submit to any authority capable of providing security, while a minority of “seekers” search to achieve stability and an alternative to the old social structures by joining extremist organizations.

The idea of a potential ‘ISIS-ification’ of southern Iraq has been criticized or denounced, as Twelver Shia thought does not traditionally suffer from extremist tendencies. Yet this process is one that could take place in any region where the social tensions are sufficiently severe—and southern Iraq certainly possesses these characteristics. ISIS is not, at its core, an intellectual religious phenomenon, but rather a sociopolitical phenomenon that uses religion as a vehicle. And the results of polling by the Al-Mustakella Research Group (IACSS) team in southern Iraq have repeatedly found the social, political, and economic manifestations that can lead to the first stage of extremism. So it is easy to predict that the second phase of extremism is not far, leading the young people of Iraq to join extremist organizations, thought, or activities.

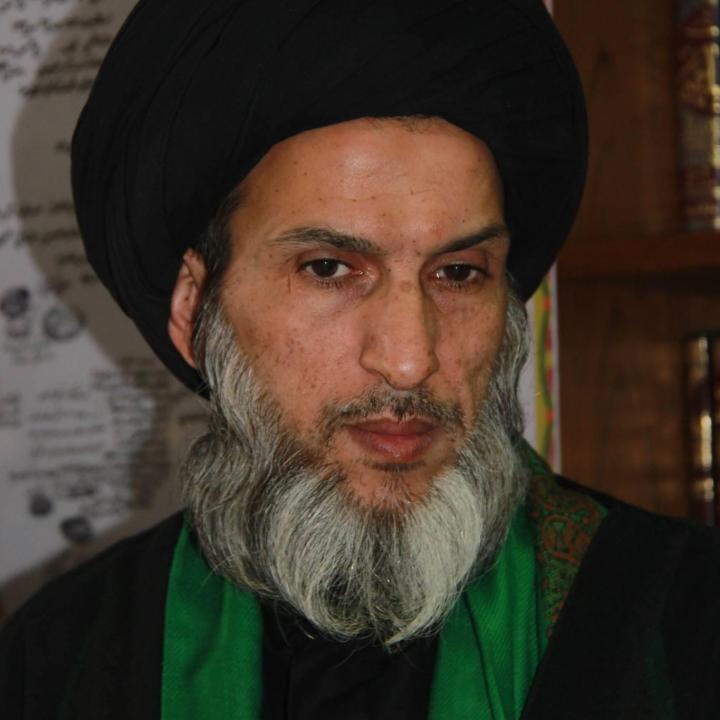

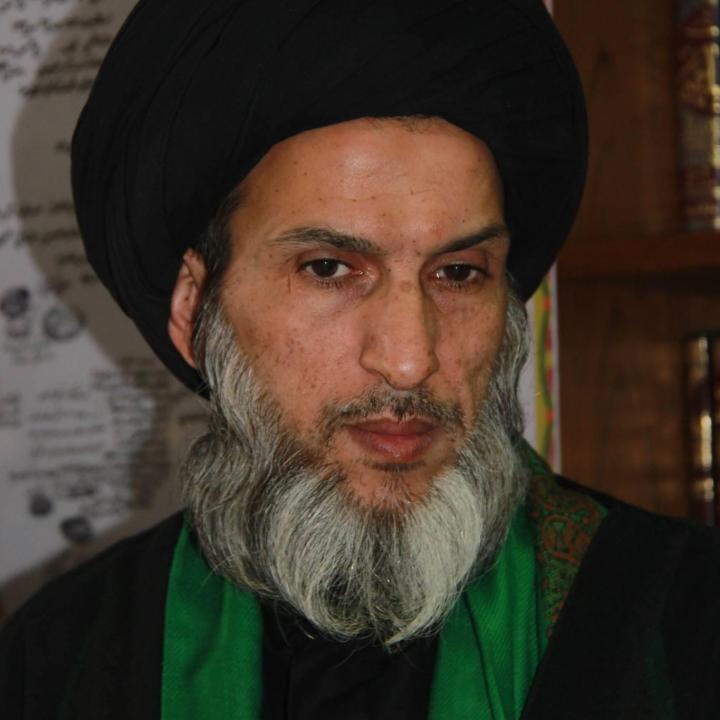

Certainly, the Sarkhis (followers of Shia cleric Mahmoud al-Sarkhi) will be neither the first nor the last symptom of this disease. During last Friday’s sermon, the Sarkhi affiliate Ali Al-Masoudi called for the destruction of Shia religious shrines, prompting angry protests and his arrest. The main thing that caught my attention as I watched the videos of the sermon, which had clearly been unified, coordinated, and deliberately timed, was not only the extremist message it contained. Rather, it was that those bearing this message were all young men. I likewise noticed this phenomenon when interviewing ISIS members in prison—most of the members had joined ISIS in adolescence or early youth.

The main characteristic that distinguishes these young men is their profound psychological need for significance. This is a natural need that drives all human beings to try to prove themselves or satisfy their sense of importance, whether constructively (work, academic success, etc.) or destructively (crimes, extremism, etc.). This need is particularly elevated among young people.

Given these circumstances, relying on security measures alone to deter youth from these movements is not an adequate approach, and will in fact inevitably increase it. It is also wrong to rely solely on an intellectual religious approach to address extremism. No matter how vigorously moderate clerics try to prove that the religion and/or sect is intellectually centrist and moderate—as is true of all religions—it will not be difficult for the theorists of extremist religious movements, including the Sarkhi movement, to pick out the religious texts and events that support their extremist view. Religious texts written ten to fourteen centuries ago are ripe for this activity, and not enough care has been taken to revise them. In short, social approaches, not religious or security ones, should be the focus of our research to address ideological religious extremism.

It is evident that ISIS itself understands this phenomenon. During an interview, one of ISIS’s intellectuals posed me this question: Haven’t you asked yourself how ISIS was able to recruit tens of thousands of fighters within a short period of time, extend its influence in this way in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere, and establish “the caliphate” while Al-Qaeda, the intellectual father of ISIS and decades its senior, was not able to realize this ‘ISIS achievement?’ When I asked him how, he replied: because we did not simply focus on the intellectual and doctrinal dimension in recruiting followers, but rather on the social, political, and psychological dimension. Anyone who has a grievance or animosity against the regime is first recruited and then ideologically brainwashed afterwards.

Like ISIS, the Sarkhi movement is only a vehicle. Anyone who wants to fight the regime, take revenge against the status quo, or express discontent and opposition to the situation he suffers from can jump onto this vehicle. Thus, fixing the political, economic, and social conditions is the key to solving the problem while acknowledging that some security approaches may be required.

And all signs indicate that Iraqis in the south are increasingly vulnerable to viewing extremism as a viable option to their societal challenges. The surveys conducted by the Al-Mustakella Research Group indicate a significant shift over the past five years in the attitudes and satisfaction of Iraqis in the south regarding the political situation, compared to the rest of Iraq’s areas. The October 2019 uprising was not a passing event, but rather the culmination of years of anger and dissatisfaction. The figures of the Iraq Opinion Thermometer, the second wave of which were published a month ago, have shown that Shia are less satisfied with their lives (and in all three components of the scale) than their brethren in central and northern Iraq. They are less happy and more distrustful of others, and feel they have less income.

Shia also showed lower levels of trust in all state institutions. While 41% of Sunnis expressed trust in the central government, 33% of Shia expressed the same. While 35% of Sunnis said the country is heading in the right direction, no more than 18% of Shia agreed. And while 47% of Sunnis gave a positive assessment of the government’s work in the security field, among Shia the percentage drops to just 31%. Only 18% of Shia, versus 31% of Sunnis, feel that the government treats them fairly and equitably.

In terms of political participation, it is clear that the people of southern Iraq and Baghdad are less inclined towards peaceful political participation to change the situation, as appears clear from participation rates in the recent parliamentary elections. More serious than that, while 57% of Sunnis expressed their opinion that armed groups are stronger than the state, the percentage among Shia jumps to about 75%. And while nearly a quarter of Sunnis support using violence against armed groups or even the government to preserve their dignity, the proportion jumps to about one third among Shia.

If we take into account the higher amount of frustration Shia feel—with Shia parties leading the government since 2003, and with southern governorates being the primary producer of Iraq’s oil wealth—then it can easily be predicted that this frustration will manifest itself further. Shia youth already took to the streets during the October 2019 protests and demonstrations. This frustration with the state will likely continue to find expression through extremist intellectual movements, both that of the Sarkhis and others, or insecurity and social breakdown accompanying the waning role of the state and the returning control of tribes, militias, and armed gangs. Here, it must be noted that the numbers expressing dissatisfaction with the political situation—and which warn of the emergence of symptoms of extremist thought and groups—have also started to clearly emerge in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The main conclusion that can be drawn from qualitative interview and polling data is that Iraq will remain a factory generating extremism in every region—south, center, and north. No ethnic or religious group will escape it so long as political deterioration and confusion prevails throughout the country. Contrary to what some believe—that the use of violence, tyranny, or despotism is the best way to tackle extremism—the only true remedy to this challenge is for Iraq to undertake a comprehensive process of political, economic, and social reform.