The Nineveh Plains and the Future of Minorities in Iraq

February 7, 2016

When the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) stormed northern Iraq and took over Mosul in the summer of 2014, it ran a parallel campaign of genocide against the minorities of the Nineveh Plains. For many of these groups, including Christians and Yezidis, this was the worst of a long list of genocides going back over a thousand years. As a result, calls for autonomy were renewed and strengthened. More Christian, Yezidi, Turkmen and other Iraqi leaders have expressed support for creating a region exclusively for minorities of Northern Iraq composed of three provinces. This could be a good path for preserving these endangered communities and could help better facilitate compensations for the loss of land, wealth, and belongings.

When discussing Christians in Iraq during the rise of ISIS, Syriac Orthodox Archbishop of Mosul Nicodemus Daoud Sharaf stated that “a Christian cannot live where law does not prevail. We can only live in a place governed by law.” Even with the relatively stable number of Christians living in Kirkuk and Erbil in the Kurdistan Region, the number of Christians has declined from an estimated 1.5 million in 2003 to around 200,000. Giving these groups the opportunity to create their own stability might be the answer to preserving their existence in Iraq.

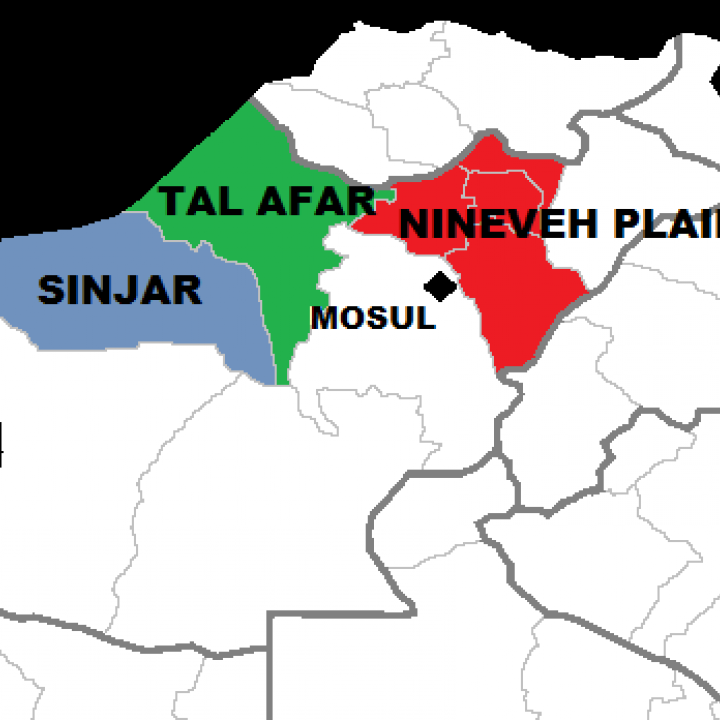

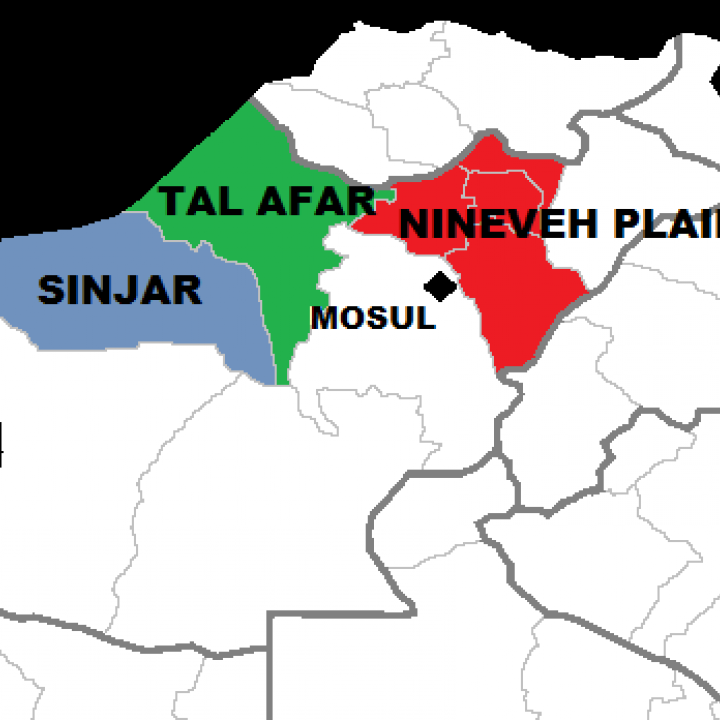

The solution for Christians, Yezidis, and other minorities in the face of persecution under ISIS can neither be to emigrate to the West, nor to stay and suffer. In order to help preserve a lasting presence of targeted Christians and Yezidis, creating a province in the Nineveh Plains for Christians and a Yezidi province in Sinjar (and Shekhan district of the Nineveh Plains) might stem their flow out of Iraq. Repurposing the districts of Tel Keif, al-Hamdaniyah, al-Shikhan and Shekhan for the Nineveh Plains province, Tel Afar district for a Turkmen province, and Sinjar district for a Yezidi province would be good ways to empower local communities. This is in line with other efforts to decentralize power in Iraq to build peace after the liberation of Mosul. Even Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi stated in April 2015 that “if we don’t decentralize, the country will disintegrate. To me, there are no limits to decentralization.”

Iraqi minorities, like the rest of Iraqi society, are people with diverse opinions and identities influenced by national, local, ethnic, and linguistic factors. In a minority-haven province, these differences will be celebrated.

Part of Kurdistan?

Federal and decentralized models of governance have been touted by many as possible solutions for post-conflict rebuilding in Libya, Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. During the US occupation of Iraq, the US encouraged tribes in the Anbar province to use self-governance and self-defense to form the Awakening Councils to fight al-Qaeda. Self-governance can serve as a safeguard from one sect overreaching their rule.

The Peshmerga recently announced it will not withdraw from the Nineveh Plains after the liberation of Mosul, so it is likely that any future for a semi-autonomous Nineveh Plains province will fall under the control of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). With Kurdistan as the main example of decentralization creating prosperity and relative stability, it is likely that the generally pro-decentralization Kurds would back a Christian-Yezidi province as long as it falls under KRG control. The KRG would also benefit from harvesting the oil found in the Nineveh Plains.

There have been Christian complaints in the past of land seizures and harassment by the KRG, as well as irritation among Yezidis at being labeled Kurds for political reasons. Both groups are also wary of Peshmerga soldiers after they abandoned positions in Christian and Yezidi villages during the ISIS onslaught. But the generally positive treatment by the KRG towards Christians and Yezidis has led to greater approval of the regional government. Furthermore, the issues Christians and Yezidis have with the KRG pale in comparison to those with other powers in the area, and many are grateful for the stability provided by the KRG.

The State of Nationalism, Diversity, and Unity

As nationalism and foreign influences spread throughout the Ottoman Empire, Christians became easy targets of violent discrimination since they were viewed as outsiders. Turkish and Kurdish forces carried out massacres of hundreds of thousands of Christians, pushing them to scatter from their homelands and congregate in safe areas, such as the Nineveh Plains.

In response to these massacres, the Church of the East shaped themselves as a modern-day Assyrian nation with claims to sovereignty and independence. Christians of the Chaldean Catholic, Syriac Catholic, and Syriac Orthodox churches did not make the same strong ethnic distinction as the Church of the East did after these massacres, but each have a degree of denominational pride. For instance, among Syriac Catholics and Orthodox there exists an Aramaic/Syriac movement based in Europe and Israel with its own flag and an emphasis on teaching the Syriac language.

It is worth noting that many Christians are followers of none of the movements and view themselves as Iraqi Christians first and foremost. Despite all of these unique differences, unity amongst Christians has been high since the ISIS attacks began. For the first time in generations, many patriarchs and representatives of the various churches have been gathering to pray and discuss their community’s situation, such as when the non-profit 'In Defense of Christians' facilitated a meeting for the patriarchs with President Obama or when an assorted group Christians met at the Chaldean Patriarchal headquarters in Erbil to discuss unity and the daunting task of returning to their destroyed homes after the liberation of Mosul.

Security Forces

If properly trained and equipped, there do exist militias that would serve as groundwork for police and security forces in a Nineveh Plains Province. There are four main Christian security forces in the Plains, all with various political leanings and party alignments: the Nineveh Plains Protection Units (NPUs), Nineveh Plains Forces (NPFs), Dwekh Nawsha, and the Babylon Brigades, who fight under the Hash’d al-Shaabi. Yezidis mostly fight under the Sinjar Alliance, which is composed primarily of the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS).

Chaldean Patriarch Louis Raphael Sako has expressed doubts about Christian militias, urging Christians who want to fight to do so with institutionalized forces such as the Iraqi army or the Peshmerga. Many Iraqi Christians similarly believe that it would be best for them to remain stewards of scholarship and civil society, and continue work towards the well-being of Iraq as a whole.

The lack of proper numbers or polling among Christians, or Iraqis as a whole, adds to the difficulty of trying to gauge the number of proponents and opponents to building a province. However, it is clear that many Iraqi Christians, regardless of background, understand the need to take action to preserve their people.

Rebuilding

Currently, Iraqi law contains parameters for a province to unite under a region (i.e. Kurdistan) but no legal pathway exists for districts to become provinces. In order for the provinces to be created, many districts of the Nineveh Province would need to devolve into smaller provinces before they are able to create a region. Whatever the future of the Nineveh Plains, it should be decided by the people who have lived there for thousands of years.

One fear is that creating a province will place an even bigger target on the backs of minorities and that in the future, the same populations who turned on their neighbors will do so again. The reality is that the target already exists, and the situation cannot get much worse than it has already. Establishing a province could help better expedite the aid process so that church organizations or Yezidi community organizations could directly aid the people. With over 70% of the towns in the Nineveh Plains destroyed, direct aid is indispensable. Diasporas would likely return to establish businesses or would invest in the province if there were guaranteed security. This sort of economic movement is necessary for people to return to their villages.

Organizations in the United States, like the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), must be called to lead during the reconciliation process. Until Iraq is politically and economically stable, decentralization may be the only way to save the fledgling country and its embattled communities. When stability returns, the diverse mosaic of Iraq’s minorities and ideas will surely return as well. In the meantime, however, Christians’ and Yezidis’ only chance of survival is self-determination and self-governance.

Photo courtesy of the Iraqi Christian Relief Council and the Philos Project.