Political Tussles in Algeria on the Eve of Parliamentary Elections

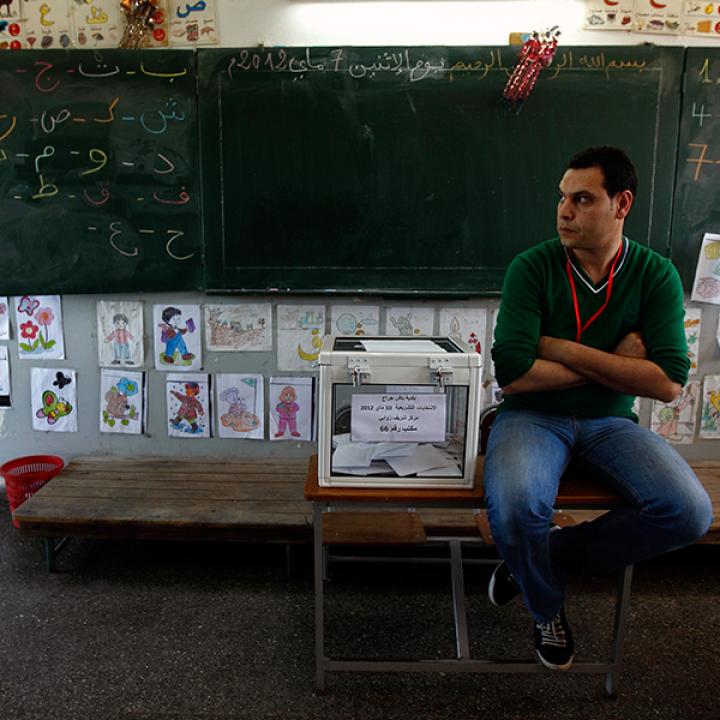

A new constitutional amendment in Algeria failed to establish an independent election body to oversee each stage of the process, from the creation of electoral lists to the announcement of results. Despite their disappointment, most opposition parties have decided to take part in the legislative elections set for May 4.

The Algerian authorities appear to have reached a compromise that avoids a major boycott of the election by the opposition -- a move that would incite unwanted domestic and international repercussions. Opposition figures and parties have long accused the administration of lack of transparency in the way it manages elections, and particularly for skewing the results in favor of pro-regime parties. The Algerian authorities fear that if the opposition boycotted the vote, Western states would sympathize with it and use the boycott as a pretext to criticize the administration, which would weaken the Algerian regime in the eyes of external powers.

Many political insiders see the coming legislative elections as a potential turning point in determining which individuals will rule the country following the next presidential election in 2019. The fact that the presidential election is less than two years away has prompted accelerated political maneuvering with the start of election campaign season, and political blocs are struggling over which people have the most political capital in the street and therefore a chance of bringing their parties to power.

A constitutional amendment stipulates that "the supreme independent authority for monitoring elections (will) oversee the administration's revision of electoral lists and draft recommendations for enhancing the legislative and organizational texts governing the process. It will also monitor the transparency and integrity of elections."

However, the "independent authority" has no power to organize elections or announce their results; this remains under the purview of the Algerian administration. The new electoral law also obliges all parties that win less than four percent of the vote in the previous legislative election to gather the signatures of 250 voters in each constituency before they can run. In order to fend off both domestic and international criticism and show the regime's goodwill in guaranteeing the poll's neutrality, the new electoral law bans several officials who hold diplomatic and judicial posts from running for election until a year after they leave their jobs, either through retirement or resignation. The Voter Records Review committee also erased from the electoral register some 730,000 people it claimed were double entries or deceased. That fits with claims by many parties and political figures that le pouvoir has inflated the electorate to what the administration says is some 23 million voters. But, they say, the real number of voters is closer to 18 million. Within this claim is an implicit accusation that le pouvoir is casting excess votes in favor of pro-regime parties.

Algeria's party spectrum is made up of three main political tendencies. There is the nationalist trend, made up of Bouteflika's National Liberation Front (FLN), the National Rally for Democracy (NRD) with which the FLN shares power, and a number of smaller parties, such as the Independent Front and the Algerian National Front. Secondly, there is the democratic trend, which promotes Berber identity, is strongest in the Kabylia region, and has long been harshly critical of the regime's "undemocratic" practices. Finally, there is the Islamist trend. Political tensions among this group have finally ended after it formed two main blocs, one of which is entering the elections as the "alliance for a peaceful society" and the other labeling itself the "federation for renewal, justice, and construction."

The May election will be the fifth legislative election to take place since the political crisis and violence that rocked Algeria in the early 1990s. However, it is arguably of minor importance given the limited weight of the legislature in the Algerian political system, which is dominated by the executive branch. The executive is represented by the President of the Republic, who has the power to form a government. This government is then headed by a First Minister whose tasks are limited to coordinating between ministries. Because the president also has a constitutional mandate to legislate on many issues, the parliament finds itself without a stable grasp on any significant power. This explains many voters' apathy toward the legislative elections, in contrast to the relatively high turnout in presidential elections, since voters view the president as the country's real decisionmaker. The previous parliament's actions -- most recently its vote for a constitutional amendment that should have been put to the public in a referendum -- caused many analysts to voice doubts about the balancing power of the legislature.

While President Bouteflika's health situation has been a constant undertone in the Algerian political discussion, it will have a particular impact on the May election. Bouteflika's health scares have forced him to stay out of the spotlight for years. In his rare media appearances, he shows signs of illness and exhaustion. That has prompted many politicians and media personalities to demand the truth about his health, in line with Article 102 of the constitution, which deals with situations in which the president becomes ill or incapable of discharging his duties. Those making such demands claim that people close to the president are effectively in charge of the country. Bouteflika's circle denies these allegations and insists that the president, despite being confined to a wheelchair, still retains his mental faculties and is very much aware of developments both inside and outside the country.

Since Algeria's independence in 1962, there has never been clarity around the transfer of power or who actually makes political decisions, runs the government, or makes policy. The army plays the most prominent role in selecting political actors and directs them during their terms in office in sync with the desires and ambitions of the army's leadership. Although Bouteflika came to power after elections in 1999, he was not democratically elected, and in fact was forced to negotiate with army generals led by General Mohamed "Toufik" Mediene in order to secure his position.

After taking power, Bouteflika worked hard to consolidate a strong presidential system by firmly seizing control of the executive and altering the constitution to procure new legislative powers. He also worked to reach a balance between power centers already within the political system, which was reflected in the makeup of his inner circle. The circle contained three prominent personalities with major decisionmaking power: Vice Defense Minister and Army Chief of Staff Ahmed Gaid Saleh, the president's chief of staff Ahmed Ouyahia, and the president's brother and special advisor Said Bouteflika. Said Bouteflika plays an especially important role in the inner circle by exploiting his proximity to the president and his strong relations with state institutions, political parties, media organizations, and business leaders.

Many political parties, particularly those in the opposition, are campaigning for this upcoming election out of necessity, as there are no genuine political alternatives in such an atmosphere of political corruption. Opposition parties have not hidden their fear of official fraud in the elections, especially as Bouteflika's inner circle raises misgivings among many over the way it has dealt with the president's health and its refusal to bow to calls to hold an early presidential election. This suggests that those who really hold power in Algeria are determined to consolidate their positions at the top of the political system and will use every means to protect their interests and stay in power.