- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Reclaiming Iraq’s Jewish Heritage

Amid growing calls for pluralism in Iraq, the U.S. should take steps to promote preservation of Iraqi-Jewish heritage, before it is too late.

On September 24, 312 Iraqi religious and civil society leaders gathered in Erbil to call for reconciling with the displaced Iraqi Jewish community and seeking peace with Israel. Although met with harsh criticism from the Iraqi government, the remarkable event was a rare demonstration of the significant extent to which Iraqis at the grassroots level identify with the country’s Jewish heritage.

That heritage is now increasingly being lost. When the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, only 35 Jews remained in Baghdad, a shadow of the over 150,000 who inhabited Iraq towards the beginning of the 20th century. The community shrunk due to mass emigration in the 1940s, driven by rising antisemitic persecution, stemming from the success of the Zionist movement and the establishment of the State of Israel.

Successive Iraqi rulers made life increasingly hard for Jews, suspecting them of collaboration with Israel and instituting a series of anti-Jewish laws. The emigration process began in earnest after 1941, when a new government, formed following a pro-Nazi coup, enabled the anti-Jewish pogrom known as the Farhud. This event rattled the sense of safety that had generally characterized the community in years prior, and brought home to many Iraqi Jews that their community had a bleak future.

As Iraqi Jews fled, the government revoked the citizenships and confiscated their properties while shaping legislation that pressured Jews to leave. For those who remained, Zionist affiliation was criminalized in 1948 and the government executed numerous Iraqi Jews accused of being Zionist or communist agents, most prominently the Basrawi businessman Shafiq Adas, who was falsely accused of both. Life for Iraq’s remaining Jews became increasingly intolerable—in the early 1960s, Iraq’s several thousand Jews were required to carry yellow cards. After the 1967 Six-Day War, Jews were banned from attending universities, receiving employment from non-Jews, or starting their own businesses. Fourteen Jews were hanged outright for their religious identity in 1969.

The overthrow of Saddam Hussein and beginning of a democratic government brought optimism that the dynamic would change, but the swift rise of an insurgency composed of former regime members, jihadists, and Shia supremacists followed by the rise of the Islamic State (IS) had all but destroyed hopes for renewing Iraqi Jewish heritage. Yet today—with the IS caliphate in Iraq defeated and growing calls within Iraq for pluralism—it is time to finally reclaim the country’s Jewish heritage.

Iraq and its Jewish Community

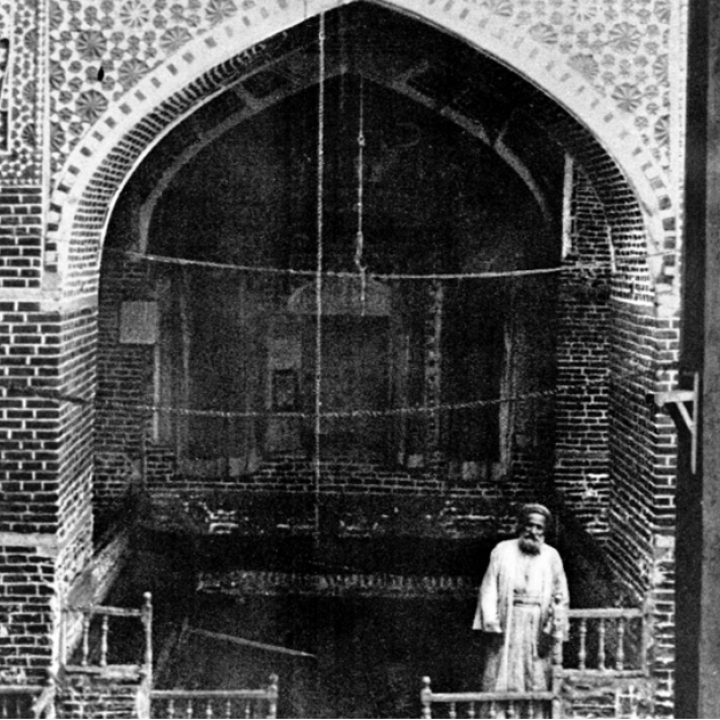

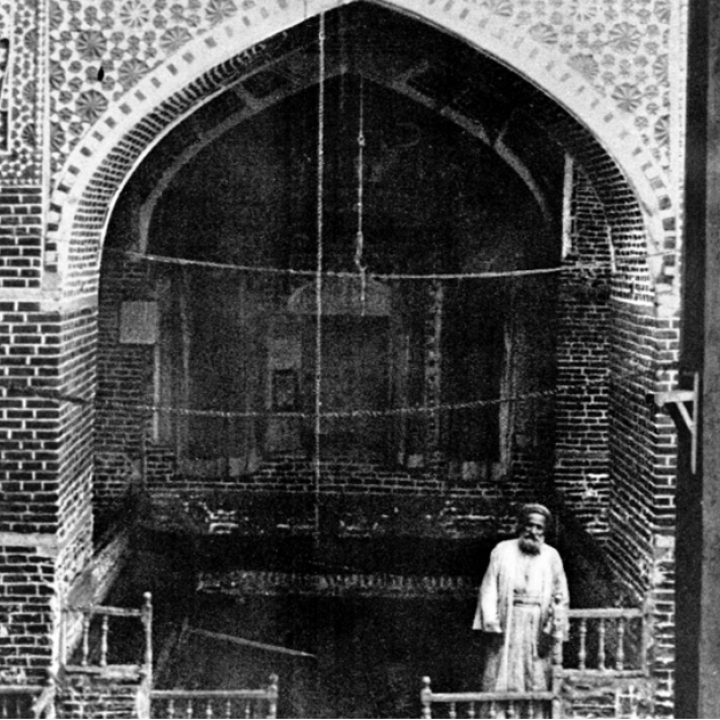

This heritage is a rich and vibrant one; the history of Jews in Iraq dates back 2,600 years. Jews first came to Babylon after the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem in the 6th century BCE. Despite intermittent periods of persecution, Jews often prospered in the Babylonian exile and were an integral part of Iraqi society, becoming successful doctors, lawyers, government officials, merchants, and artisans. In Baghdad’s markets, Jews were prominent jewelers, smiths, and cloth dealers while in Basra, many Jews worked at the important port authority. By the early 20th century Jews made up a significant portion of Iraq’s three largest cities: making up to 40 percent of Baghdad’s population, as well as a quarter of Basra’s and a significant portion of Mosul’s populations. By the late 1940s in Baghdad, the Jewish community was funding over 60 synagogues, schools, hospitals, and health clinics.

Iraqi Jews also prominently participated in Iraqi society during the interwar period. In 1921–when the Kingdom of Iraq under British Administration was established—Jewish financier and government official Heskel Sassoon was appointed its first minister of finance, and was instrumental in creating the new Iraqi state’s institutions. Jewish musicians gained much popularity in Iraq, and the ensemble representing Iraq at the 1932 First International Congress of Arabic Music in Cairo was composed mostly of Jews. One member of the ensemble was famous Jewish ‘ud player Ezra Aharon, who was presented gifts as late as 1948 and 1949 by Iraqi regent Abd al-Ilah and prime minister Nuri al-Said, respectively.

Pluralism in Iraq had reached a high point. In his first speech, King Faisal I invoked the integral place of Jews in Iraqi society, “there is no meaning for words like Jews, Muslims, and Christians within the concept of nationalism. This is simply a country called Iraq and all are Iraqis.”

Reviving Interest in Iraqi Jewish Heritage Today

Today, there are few living reminders of this past. Only three Jews remain in Iraq and efforts to reinvigorate the Jewish community have been few. There are exceptions, such as the preservation of the tomb of the Jewish minor prophet Nahum in Alqosh with the support of the U.S. government, the Kurdistan Regional Government, nongovernmental organizations, and private donors. This is particularly important considering a report published last year by the Jewish Cultural Heritage Initiative that almost 90 percent of Jewish cultural sites in Iraq are in severe disrepair or beyond repair.

More hopeful is the broader shift in Iraqi society toward greater pluralism along with a rising awareness of Iraq’s Jewish history. For example, Omar Mohammed—the Iraqi historian known for his covert reporting on the IS occupation of Mosul (2014-2017)—rediscovered the city’s Jewish history while doing research for his Mosul Eye blog. He now works to revive interest in Mosul’s Jewish heritage through his work and highlighted the work of a group of young volunteers in Mosul to restore synagogues and other historical sites last year. Also indicative of this trend is the 2016 publication in Iraq of a two-volume Arabic history of Iraqi Jews and other later works on the topic by Iraqi author Nabil Abd al-Amir al-Rubei’i.

On the political level, there has also been an important gradual shift toward pluralism. Since 2014, Iraqi prime ministers have been fairly moderate, even if politically weak compared to European prime ministers. Especially after the devastation of cultural sites by IS, there has been a desire to revive a collective sense of Iraqi national identity inclusive of minorities and a rejection of sectarianism and increasing Iranian influence. This is reflected in the success of Moqtada al-Sadr’s nationalist nonsectarian Saairoon bloc in the 2018 Iraqi parliamentary elections, as well as Sadr’s statement that year that he would welcome the return of Jews expelled from the country given “their loyalty was to Iraq,” the first time an Iraqi politician has addressed the issue in years.

While Muqtada al-Sadr is hardly a political figure interested in normalization, there are even signs that some in Iraq are interested in reversing the country’s strongly antagonistic policies towards Israel. The bulk of the Iraqi Jewish community—over 220,000—lives in the Jewish state, and dialogue with Iraq would facilitate efforts to preserve Iraqi Jewish heritage. Israel has certainly expressed informal interest in reaching out to Iraqis, including promoting dialogue with its Arabic-language “Israel in the Iraqi Dialect” social media campaign, which received some positive engagement from Arab users. In addition, following the recent normalization of relations between Israel and several Arab countries, some Iraqi politicians have shown a willingness to explore normalization themselves, but this issue is fraught with heavy opposition from influential Iran-aligned militias in the country and anyone for normalization has generally not publicly stated so out of a justified fear of reprisal. These militias have already responded to the recent Erbil conference with threats against those who attended and “jihad” against “Zionist-American dens.” Nonetheless, the growing, albeit cautious, openness toward Israel is another sign of hope for recovering Iraqi Jewish heritage.

With the Jewish community almost nonexistent within Iraq while Iran-aligned forces are on the rise, time is running out for preserving Iraq’s Jewish heritage. Consequently, the United States should see promoting interest in the subject as important both as a way to foster efforts towards pluralism in Iraqi society and as a humanitarian issue. Promoting the restoration of cultural sites like the tomb of Nahum—among other decrepit synagogues, cemeteries, and tombs—is one important line of effort. U.S. State Department and USAID support can be focused through collaboration with NGOs and individuals working on restoration. To raise awareness of the issue, U.S. personnel might highlight restoration efforts in press releases or offer to help with security for visitors promoting them. The same goes for efforts to restore the historical sites of other minorities, like the Lalish Yazidi temple or Mosul’s Christian churches and monasteries, to preserve Iraq’s multicultural, pluralistic heritage.

Ultimately, visits by people previously displaced from Iraq should accompany these efforts, but this is dependent on the security situation. The children and grandchildren of displaced Iraqi Jews (myself included) were passed down very positive stories about life in Iraq before 1941. They generally do not seek to move to Iraq, but there is great interest in visiting the place their ancestors called home for over two-and-a-half-millennia and perhaps actively assisting in reconstruction. From this perspective, the U.S. presence in Iraq is essential since its counterterrorism mission has the second-order effect of safeguarding cultural sites and Iraq’s remaining minorities, as it did in Afghanistan before its withdrawal.

Aside from security, the Iraqi government would make a major statement by facilitating travel for Jews displaced from Iraq, possibly by offering special visas or citizenship to those whose families had fled. U.S. government personnel can help by assisting in organizing meetings between leaders in the field of Iraqi Jewish heritage and Iraqi authorities interested in the topic.