- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

The Rise of the Taliban and Iran’s Critical Problem in Afghanistan

Facing a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, Iran is likely to pursue pragmatism based on mutual interests and forgo escalation, even in the face of growing terrorist threats.

On October 27, numerous foreign ministers gathered for a meeting in Tehran to discuss the situation in Afghanistan. There, Iranian FM Hussein Amir-Abdollahian emphasized that “it is essential that the Taliban adopts a friendly approach towards its neighbors” while expressing concern for Afghanistan’s economic crisis and calling on the Unites States to lift sanctions.

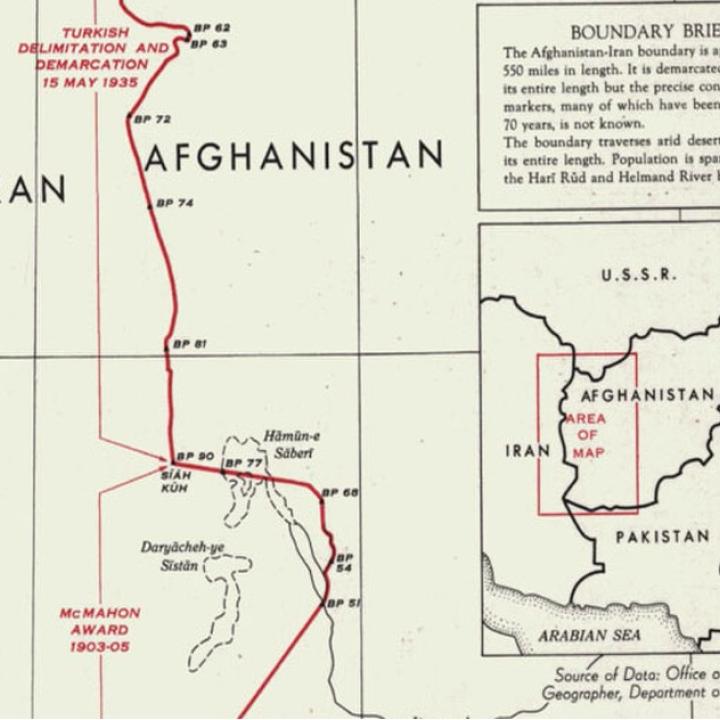

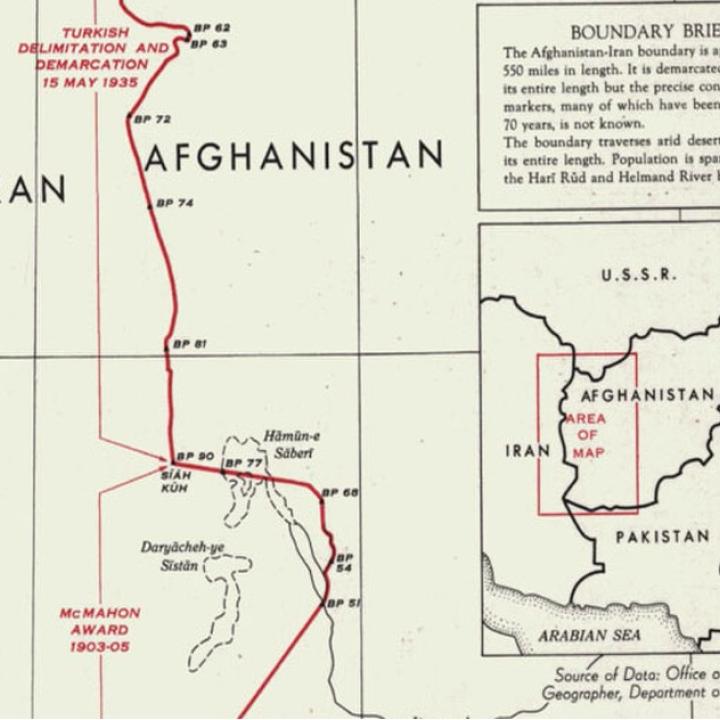

The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s seizure of the reins of power in the country has brought the complex nature of the relations between the Taliban movement and Iran to the fore. While Iran is undoubtedly concerned over its nearly 900 km border with Afghanistan—with the ongoing potential for more refugees, smuggling, and drug trafficking—as well as the Taliban’s treatment of Afghanistan’s Shia minority, the Taliban’s takeover is a reality that Iran must now live with. While Iran is actively looking to use diplomacy to term per the Taliban, provocations are unlikely be answered by force even as Afghanistan’s circumstances become increasingly perilous.

While characterized by enmity during the first period of Taliban control of Afghanistan, Iran’s relations with the group became more conciliatory in past decades as former Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani developed working relations with the movement. Soleimani made efforts to unite against the American forces deployed in Afghanistan out of a common hostility to the United States. Iranian messaging has always criticized the U.S. presence in Afghanistan as part of its broader opposition to the U.S. presence in the region, which heightened further after the U.S. killing of Soleimani.

Aside from a regional perception of U.S. failure in Afghanistan, Iranian officials’ rhetoric also emphasizes the country’s solidarity with liberation movements—including the Taliban—across the world, often regardless of other ideological orientations. Leaders of Iranian-backed militias view the Taliban’s swift victory as a model for their own interests, and have called for a similar outcome in Syria and Iraq. This is even as Iran has linked its formal recognition of the Taliban government to its implementation of an ‘inclusive government’ and condemned the Taliban’s fight against oppositionists in the Panjshir valley, which the Taliban has just announced as “under our command.”

While Iran is nominally supportive of the Taliban as a governing body, it also fears the movement, both for its tenuous grasp on the country and hardline elements inside the organization. This is especially the case as the Taliban has demonstrated its failure to prevent the bombing of several Shia mosques in October, claimed by Islamic State Khorasan Province. And while Iran may not fear the rise of the Taliban as a whole, it is likely nervous about the hardline approach of the Haqqani Network—a branch of the Taliban that maintains ties to al-Qaeda and other Sunni extremist groups—and what may happen to Taliban-Iran relations if this network becomes ascendant. Its leader is currently the Interior Minister of Afghanistan’s government—theoretically responsible for countering terrorism inside of Afghanistan—and could well tilt Afghan-Iran ties if he continues to gain ground in the new government.

Still, there are several reasons why Iran is likely to avoid any kinetic action, even if the security situation within Afghanistan worsens. Were Iran to escalate against the Taliban, its best option for confronting the organization would be utilizing the The Liwa Fatemiyoun—an Iranian-backed Afghan militia currently fighting in Syria and originally established in 1996 under Ahmad Shah Massoud—but doing so would entail risks likely unpalatable to an Iranian government facing its own internal challenges. Notably, Iran’s ability to recruit for this brigade is severely curtailed given the small Shia population in Afghanistan and the absence of strategic depth linking Iran directly to the areas of deployment. On the other hand, Iran has reason to fear that the Taliban could successfully mobilize Afghani Iranians against Tehran in the case of soured relations.

Furthermore, escalation with the Taliban could encourage a swath of armed jihadist groups to put their doctrinal differences aside and join Taliban-led efforts against Iran. These include the Baluchi armed movements in southeastern Iran, which consist of ethnically Afghani Iranians. Most notable is Jaish al-Adl, a group with ideological and methodological links to the Taliban, that engages in sporadic confrontations with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Iran is wary of repeating the scenario in Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998, when the Iranian consulate was targeted by Taliban militia and eight Iranian diplomats were killed, almost triggering open conflict between Afghanistan and Iran.

Iran’s foreign policy pragmatism has so far allowed it to navigate many of the strategic inconveniences that a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan entail. The state of conciliation that brought the movement together with Iran in the post-invasion stage indicates that Iran may well successfully re-weave the threads of this old relationship by capitalizing on mutual interests, such as opposing ISIS, oil sales, and cross-border drug trade. As the recent conference demonstrated, Iran will also seek to leverage the role that China, Qatar, Russia, and Pakistan can play in refining the Taliban’s discourse and behaviors, given that the Taliban is looking for international recognition and political/economic support to maintain control of the country. However, the success of these efforts depends on the ability of the Taliban to successfully navigate the economic, extremist, and humanitarian crises fast approaching the country.