- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

Turkey’s Elections: a Referendum on the Future of the Republic

Though the Turkish opposition has a serious shot at unseating Erdogan, their success is far from guaranteed—even if they win in the polls.

This year, Turkey celebrates one hundred years of a secular republic after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1923. However, the results of this week’s elections on May 14 will provide a sense of whether the republic will continue or flounder. Much is at stake for Turkey's 83 million citizens, and the election is viewed by many as a referendum about Turkey's future: democracy versus non-democracy, and a choice between a secular or an Islamist state.

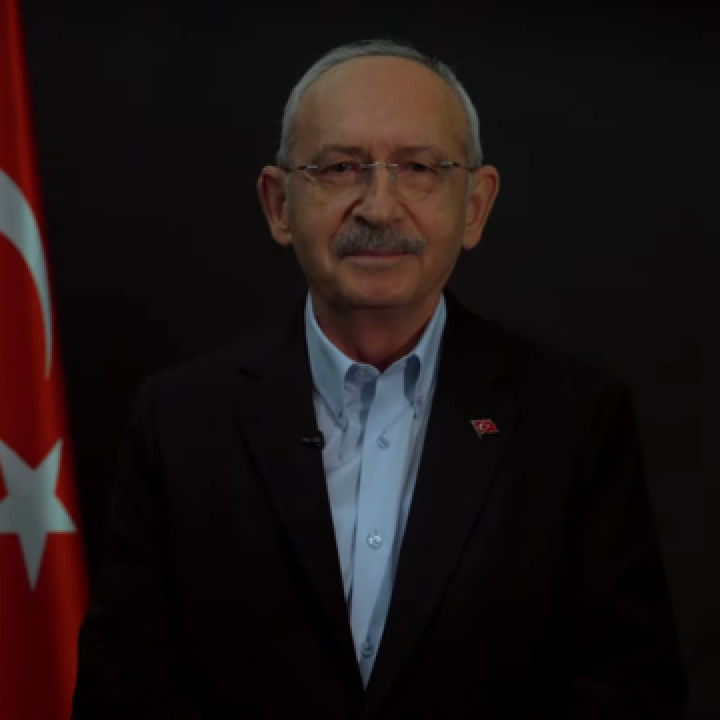

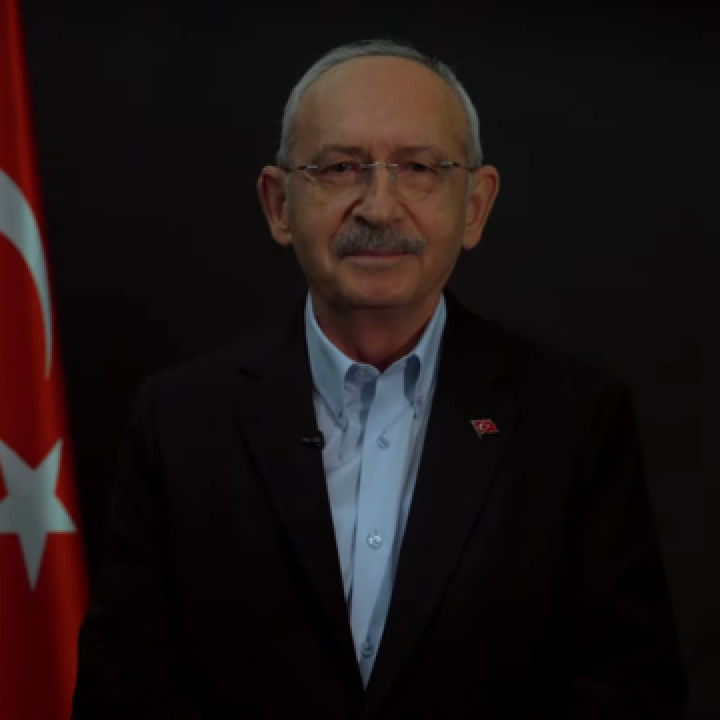

The major participants in the elections are incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his opponent Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the candidate from a large anti-Erdoğan alliance representing a coalition of six opposition parties. This alliance seeks to strengthen the power of the parliament and roll back many of the constitutional amendments Erdoğan has made in his presidency. The alliance is also running on the promise to enhance the legal system and the rule of law, strengthen freedom of speech and the press, and release political prisoners. While other candidates included ultranationalist Sinan Ogan and social-democrat Muharrem İnce—predicted to get about six or seven percent together—the latter has now withdrawn, suggesting that a good portion of İnce’s votes will go to Kılıçdaroğlu instead.

One fact is indisputable: Erdoğan, who currently controls the legislative, judicial, and executive powers, may well lose the elections based on several recent opinion polls. The deteriorating economy, the empty treasury, the falling currency, the regime’s ineffective actions during the biggest earthquake in Turkish history on February 6, and Erdoğan's demonizing and polarizing rhetoric may well push voters to support an end to the Erdoğan era.

The country’s recent devastating earthquake is one especially stark example of the issues deeply frustrating Turkish voters. Erdoğan has extensively supported building roads, tunnels, airports, and houses, but the earthquake clearly illustrated that Erdoğan engaged in fraudulent construction with the help of five oligarchs close to the president. Poorly constructed buildings that did not meet safety codes collapsed like houses of cards, crushing the people inside. The criticism of Erdoğan's permits for these projects is harsh, although the government has tried to silence criticism against management of the disaster. Erdoğan—who came to power two decades ago because of a failed rescue effort following another earthquake—well knows the power of this type of event on the electorate. On top of it all, the earthquake has hit provinces where Erdoğan traditionally has had the most support. The botched rescue effort in these areas may cost Erdoğan.

Erdoğan has also deeply eroded his popularity with Kurds and women, voters who once helped carry him to power. Erdoğan has likely alienated some female voters with his disparaging remarks about women, but the loss of the Kurdish vote is especially probable. Erdoğan rules with the support of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the Islamist Hüda-Par, whose rhetoric demonizes Kurds, and Ankara's support of violent Islamist groups in Syria against the People's Defense Units (YPG) has terrified and angered many Kurds inside Turkey.

With all of these factors working against Erdoğan in the polls, there is one pressing issue discussed in the weeks leading up to the election: what happens if Erdoğan does not respect the results? The recent extradition of former Peruvian ex-president Alejandro Toledo to prison in Peru after corruption scandals is a frightening precedent for Erdoğan. Several observers have suggested that Erdoğan will not give up power easily. There is a potential risk, for example, that Erdoğan's private security apparatus SADAT will take up arms on election night.

Moreover, even if Erdoğan does lose the elections and accepts the results, it will not necessarily be smooth sailing for the new government. Erdoğan’s years in power have fueled ethnic, religious, and political resentments across the board. His incremental Islamization of Turkey has polarized the country and heightened tensions domestically. And his military incursions in Iraq and Syria have dragged Turkey into costly and dangerous missions with no clear end result.

Furthermore, the anti-Erdoğan Alliance will face its own challenges were it to come to power, specifically from Turkey’s Kurdish minority. Although Turkey’s largest pro-Kurdish party, the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), has endorsed Kılıçdaroğlu, they are not formally included in the coalition. Some within the opposition alliance follow an ultranationalist and a Kemalist vision for Turkey that does not condone any form of Kurdish self-rule or even more liberalization. None of the parties in the alliance want to recognize the Kurds' right to its own language and identity in the Turkish constitution. Neither do the secular parties in the alliance recognize the genocide of Christian Armenians, Assyrians, Syriacs, Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks during WWI.

On questions of foreign policy, none of the parties in the alliance have presented plans to withdraw Turkish soldiers from Libya, Iraq, or Syria. To avoid losing nationalist Turks' support, the alliance parties adopted the same foreign policy as Erdoğan during the election campaign. At present, there is no clear answer to what kind of foreign policy changes—if any—a new Turkish government without Erdoğan will pursue. All these factors point to a situation whereby a number of conflicts will still be present in Turkey, even if Erdoğan loses the election.

The only thing to be said for certain, therefore, is that the Turkish elections will concern and affect many more people than just the Turkish voters. Meanwhile, the combination of domestic criticism of Erdoğan's mishandling of the earthquake—and the corruption highlighted in the aftermath—along with heightened unease of the open-ended military missions abroad make for a volatile mix that will probably persist regardless of who wins the election.