Since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, the Iraqi state has successfully weathered a series of security crises that united the public against a common enemy. For example, during the war with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Iraqis from different backgrounds joined forces and rallied behind the government. Yet after the fighting ended, national politics became marred by corruption and self-serving agendas once again, while the public’s support of the country’s leaders morphed into a wave of protests against poor governance.

Indeed, the government have so far failed to solve or unite the country around the types of challenges that are currently holding Iraq back in the same way it did around security challenges. Nonetheless, the current wave of protests may actually provide Iraqi leadership with an opportunity to incorporate popular criticisms and enact a new agenda that would once again bring the country together.

Applying the methodological framework of leadership expert Keith Grint, it appears that Iraqi leaders focus on critical problems (crises) while neglecting ‘tame’ challenges—recurring problems fixable through the steady application of the logically appropriate solution—and ‘wicked’ challenges—those issues that can only be addressed with imperfect solutions, which must be weighed against the original challenge.

This strategy has had dire consequences for the general level of Iraqi governance. Critical problems require a different management strategy than the other types of challenges: the swift and decisive mode of authority applied to the country’s security crisis since 2003. However, the reliance on authority has come at the expense of the competent administration, patience, and flexibility required to manage ‘tame’ problems, such as the continued weakness of Iraqi services infrastructure.

Moreover, successive Iraqi governments have made no progress dealing with Iraq’s wicked problems. To be sure, these challenges are naturally the most difficult to address, especially given that the relationship between cause and effect is often unclear. Iraq’s corruption and the stifling bureaucracy are good examples of these relatively intractable issues. In order to manage these types of challenges, vision is paramount—a quality that Iraqi leadership has lacked.

Iraq’s governments have demonstrated just how key vision is in what has and has not been accomplished in the past fifteen years. Iraq had a strongman in Maliki and a unifying figure in Abadi, yet neither leader displayed ‘vision’ to tackle the country’s issues beyond its security crises. This is why Iraq struggles to have a clear candidate for the premiership every four years other than the incumbent prime minister and has had an unexpected compromise candidate chosen in two of the last three government formations.

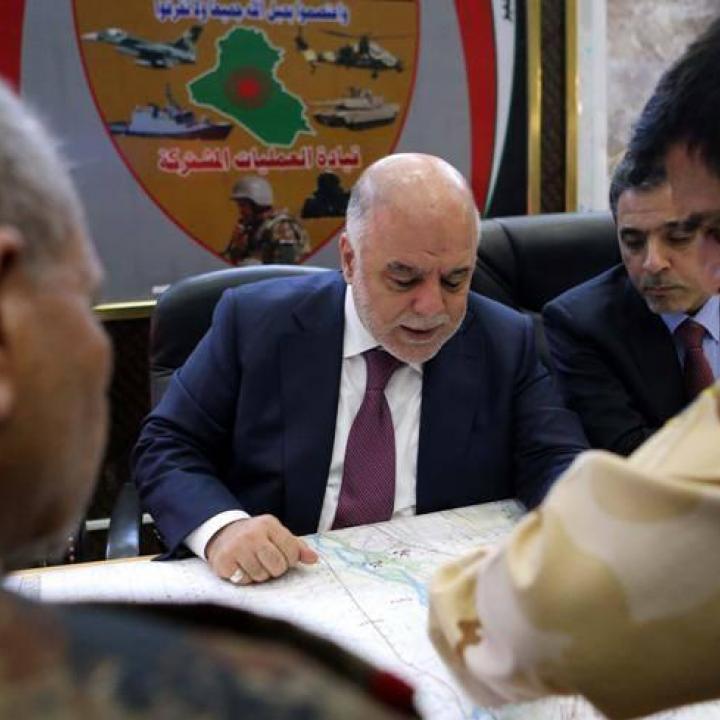

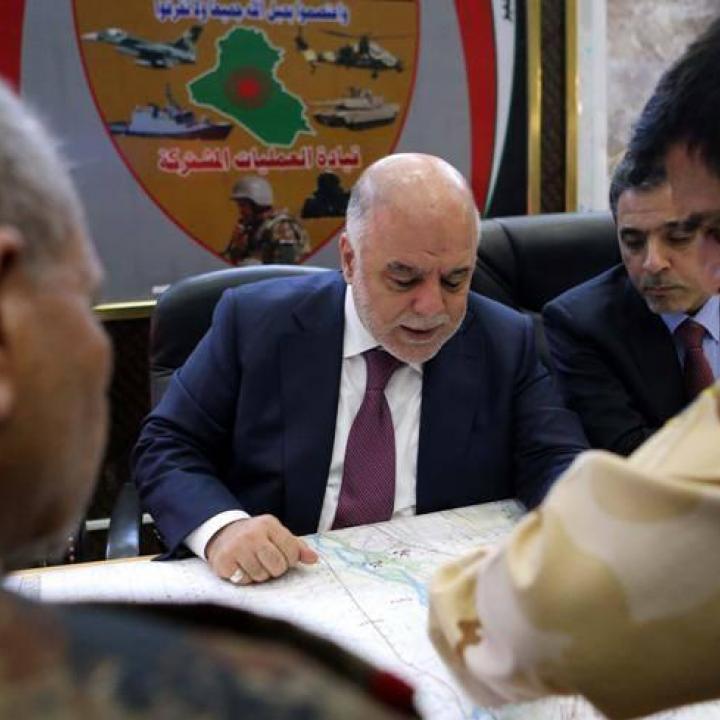

When Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi first took office in 2014, his diplomatic demeanor was interpreted as a suitable leadership style for peace rather than war. However, Abadi proved his ability to unite different factions to govern alongside him. ISIS was defeated under his leadership, and the crisis of Iraqi Kurdistan’s referendum was managed in a way that prevented subsequent destabilization of the entire region.

Abadi has demonstrated that he possesses many of the qualities that characterize a good leader, but the task ahead of the next prime minister will need more than just individual qualities. The position requires someone who provides a uniting vision rather than a threat for Iraqis to rally behind, and through this vision tackle the country’s critical, tame, and wicked problems in a competent way. Now in a time of improved security, the government’s continuing failure to provide services or tackle corruption and bureaucracy can tarnish not just Abadi’s legacy, but that of post-Ba’athist Iraq altogether.

However, there is some sense of optimism in the popular demands for visionary leadership spreading from the south of Iraq. Ongoing protests have shown that Iraqi citizens will not allow the government to continue neglecting Iraq’s wicked and tame challenges any longer.

There are certain strictures on what type of government can respond to protesters' demands in a satisfying way. A vision for Iraq must come from a political leader; the religious establishment cannot and will not become directly involved because the Iraqi system is not a theocracy. Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani has intervened in political discourse only when the existence of the Iraqi state was in question, and did so to emphasize the country’s democratic qualities. And while Sistani’s representatives give weekly political sermons, these function as advice for citizens and political leaders rather than a kind of de-facto law. Thus, Iraq’s political leaders must fix the issues of their own governmental structures, like unreliable services, corruption, and bureaucracy.

Given the dangers of foreign intervention and a developing tendency among youths towards authoritarian nostalgia, a continuation of the status-quo in governance will not only push the people into further hardships, it could ultimately threaten Iraq’s democratic system if a ‘visionary’ authoritarian regime emerges that promises the services Iraqis so desperately need.

In order to avoid this potential future, the next Iraqi government should take heed of the appeals of the current demonstrations: unified in demands and larger in scale, these protests are unique and, if better organized, could create a ‘sense of urgency’ essential for governmental change. As transformation experts suggest, these voices may provide the necessary pressure to force Iraq’s leaders to develop a vision for change, ironically turning the country’s wicked and tame problems into a crisis in and of themselves.

The vision Iraq needs is one with an objective and diverse economic and energy policy to strengthen the Iraqi state and improve its ability to balance foreign policy between regional actors as an independent partner. A stronger Iraqi state accompanied with better services and less corruption and bureaucracy will allow a democratic leader to rally all factions of Iraqis behind him or her.