- Policy Analysis

- Fikra Forum

What to Expect from Cairo’s Strategy with the New U.S. Administration

Sisi may need to respond to U.S. pressure over human rights issues, but he knows that Biden will not willingly damage relations with Egypt.

The unfortunate events in Washington DC, where a mob attempted to storm the Capitol building and prevent members of Congress from endorsing Joe Biden’s victory in the presidential election, echoed widely in Cairo. Caught between sympathy, anxiety, amazement, cynicism, and apparent gloating, opinions were divided. But it was noticeable that many media professionals affiliated with the regime found this moment as an opportunity to promote, in sarcastic language, the idea that the democracy demanded by the opposition and activists is useless and unstable. They go on to say that the stronghold of democracy is being violated, and therefore the iron hand is the best guarantor of national stability.

The Egyptian regime itself sees what happened as a fortunate distraction for the new U.S. administration that could keep it from focusing on issues of freedom and human rights that worry Cairo. In late December, Mahmoud Badr—an Egyptian MP close to the regime—tweeted his comments on recent European resolutions regarding Egypt’s human rights situation, stating that “the resolutions adopted by the European Parliament are a sign of what is to come and the political blackmail that Egypt will face. These resolutions are a token of love from the European Parliament to Joe Biden.” These two resolutions call for a transparent investigation and comprehensive review of the EU’s relations with Egypt in light of the ongoing crackdown on human rights defenders, members of the opposition, and civil society leaders in Egypt.

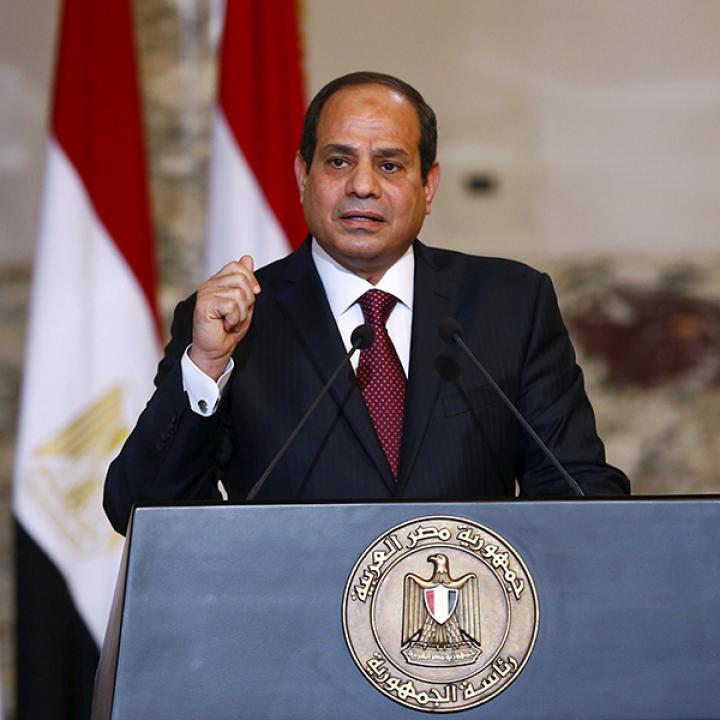

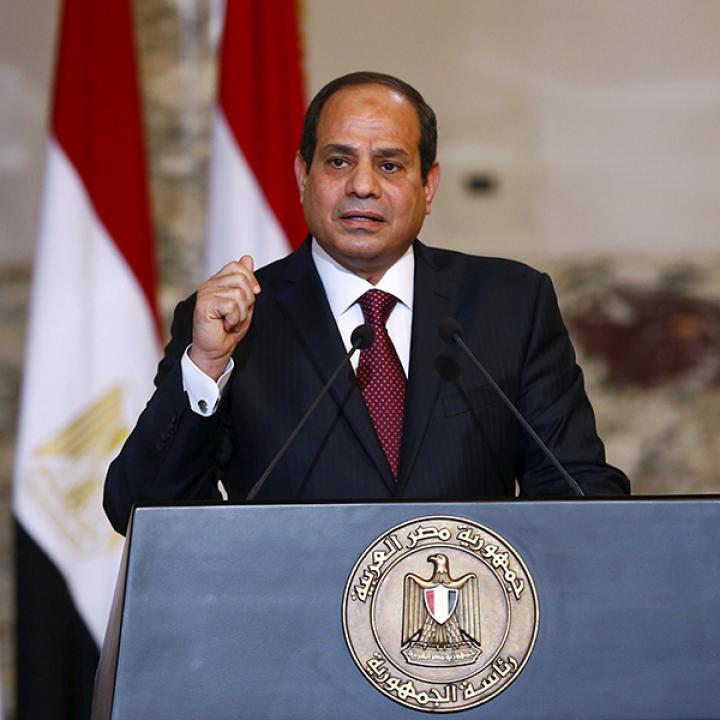

MP Badr’s tweet is a clear indication that the Egyptian regime fears the international pressures it may face from the new U.S. administration when Biden takes office. During the past four years, Cairo has enjoyed warm relations with Washington due to the convergence of views between the U.S. president and his Egyptian counterpart Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, who Trump once joked was his “favorite dictator.”

Sisi has been counting on Trump since the beginning of the president’s first campaign in 2016, when Sisi clearly stated his support during a television interview with CNN. There, he stated that “there is no doubt” when asked if he believed Donald Trump would be a strong leader. It was an unusual step for a world leader to take—foreign leaders rarely support one candidate over another during U.S. elections, since this could damage relations with the new president.

Sisi’s eagerness to show a preference for the Republican candidate was a response to Hillary Clinton’s attacks on his regime, which she described as an “army dictatorship.” Some press reports have indicated that there were federal investigations underway regarding whether Sisi’s support for Trump also included financial contributions. The investigations examined links to a state-run Egyptian bank after $10 million was sent to Trump’s 2016 campaign.

Regardless of the extent of Sisi’s support for the Trump campaign, it is clear that the Egyptian regime has benefitted from good relations with the White House during the Trump presidency. The Trump administration has openly supported Sisi on a number of issues, turning a blind eye to repeated human rights violations and taking Egypt’s side on the issue of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

However, the Egyptian regime realizes that this warm relationship will not continue once the Democrats take office. The first sign of the end of this honeymoon period between Cairo and Washington may have come from Joe Biden himself, who tweeted on July 12, 2020: “No more blank checks for Trump’s favorite dictator,” in reference to the human rights situation in Egypt.

Since the Democratic victory in November, the Egyptian media has also expressed clear concerns that the new U.S. administration might intervene in its internal affairs, particularly with regard to civil liberties. As a result, the Egyptian government has tried to lobby Washington to support its perspective, hiring the firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck to provide public relations services in a $65,000-per-month contract.

In an effort to test the waters of the international community immediately after Biden’s victory, Egypt decided to arrest three members of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR). These members of Egypt’s most prominent human rights organization, with widespread international recognition, were arrested after meeting with several European ambassadors in their headquarters and publishing photos of the meeting on their official social media pages. This reckless move on the part of the regime was intended to send a clear message that it had no intention of loosening its grip domestically because of the new occupants in the White House, nor would it under any circumstances allow for the return of the kind of external pressures that had been employed against Egypt during the Mubarak era.

The Egyptian regime’s initial evaluation of the situation was that there was likely to be pressure to release the EIPR leadership, but that key countries such as Germany and France would not want to risk losing Egypt over a few cases like this. Egypt is a key customer for Western arms sales and serves as a safety valve for illegal immigration to Europe. The regime therefore believed that if it could withstand this wave of criticism with minimal losses, it would send a clear message that Cairo’s arm could not be twisted.

Nonetheless, the regime was taken aback by the tremendous subsequent pressure from international organizations and public figures. Even EIPR was surprised by the backlash. The issue was further complicated by the fact that this international campaign coincided with Sisi’s scheduled visit to France, which was then threatened by this powerful wave of criticism. This forced the regime to reverse its decision and release the EIPR leaders before Sisi travelled to meet with Macron, who gave him a very warm state welcome in keeping with the profound shared interests between the two countries.

Whether it was the international pressure alone or the combined effect with Sisi’s visit to Paris that led to the release of the EIPR leaders, this trial balloon had clearly shown the regime that entirely disregarding these outside pressures is not possible. This leads us to the most important question on this issue, namely, how will Cairo deal with the anticipated pressures from the Biden administration on the matter of civil liberties in Egypt?

Though it is understood that there will be considerable pressure regarding civil liberties in Egypt when Biden takes office, the regime believes that there are inherent limits to these pressures. The Biden administration may play its most important card here, i.e., leveraging aid to Egypt, but it will not go so far as to cut off aid. That would mean losing Cairo entirely and pushing it toward China and Russia, and the United States will certainly not want to lose an important strategic ally.

The major problem that the Egyptian regime will face is that the danger of complying with the new U.S. administration’s wishes may be far greater than the consequences of disregarding them. From the beginning, President Sisi has focused on establishing an image within Egypt of a strong and stable regime that is able to maintain a tight grip on its affairs, and to crush any force that poses a threat to the stability of the country or that could propel it toward the fate of Syria or Iraq. The regime’s backing down in this case, particularly in light of a change in U.S. administrations, suggests to its enemies that it has been shaken and is unable to maintain its ground. Such a perception poses a real threat to the regime, and backing down under pressure is therefore a risk that it cannot take. At the same time, the recent experience of detaining the EIPR leadership and then reversing the decision and releasing them has demonstrated that it is not possible to fully ignore foreign pressures.

Therefore, the ideal solution for the regime is to negotiate a middle ground between confrontation and compliance by creating the illusion of a space for civil liberties and releasing some political detainees, provided that this happens quietly and over an extended period of time. In this way, it will be able to placate foreign powers to some extent whenever pressure increases or criticism intensifies. At the same time, the regime would not appear to be turning back in the face of internal opposition, which could cause opponents to mobilize against it. This strategy seems to be logically consistent with Sisi’s philosophy of ruling by force. However, it will depend to a great extent on Cairo realizing that no matter how much resistance is shown, the Democrats will not engage in confrontation past the point of no return.

Maged Atef is a freelance journalist based in Egypt. He has contributed to a number of publications, including BuzzFeed, Foreign Affairs, and the Daily Beast.