- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3472

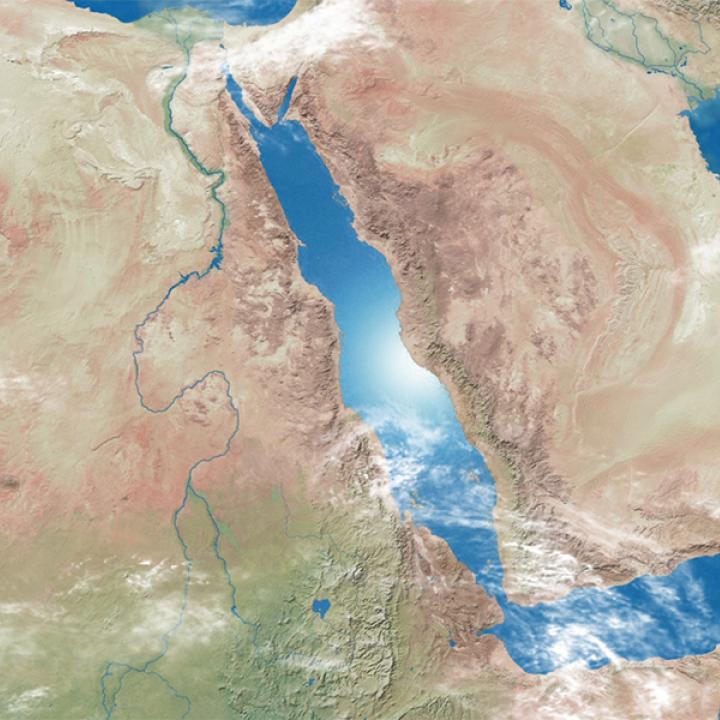

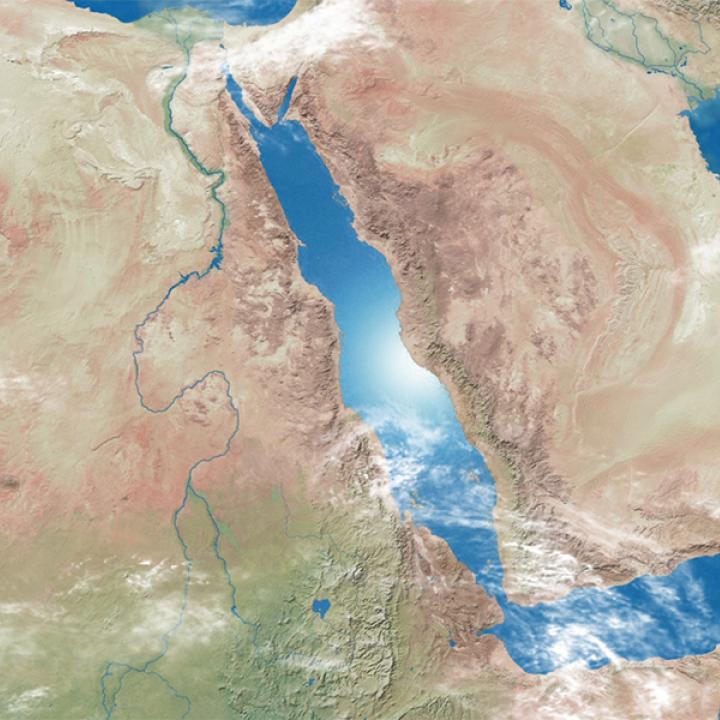

Don't Part the Red Sea: Formulating Holistic Policy Toward a Key Region

A former NAVCENT commander joins a panel of distinguished diplomats and experts to discuss why Washington should approach the region’s disparate economic, political, and security issues in a more integrated fashion.

On April 15, The Washington Institute held a virtual Policy Forum with John Miller, Susan Ziadeh, Tibor Nagy, and Elana DeLozier. Miller retired from the U.S. Navy in 2015 as a vice admiral after serving as head of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command. Ziadeh served for twenty-three years in the State Department, including as deputy assistant secretary for Arabian Peninsula affairs and ambassador to Qatar. Nagy’s three-decade foreign service career included time as assistant secretary of state for African affairs and ambassador or deputy chief of mission to several African nations. DeLozier is the Institute’s Rubin Family Fellow and author of its Transition 2021 memo on the Red Sea region. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

John W. “Fozzie” Miller

Chokepoint security remains the top military concern for CENTCOM and other authorities with regard to Red Sea waterways, namely the Suez Canal, Straits of Tiran, and Bab al-Mandab Strait. Incidents such as Houthi shipping attacks emanating from Yemen have raised serious security concerns, and the days-long blockage of the Suez by the grounded tanker Ever Given showed how crucial these chokepoints are to global trade. Perhaps the best way to prevent the latter type of incident is to expand the Suez for constant two-way traffic.

More broadly, countries outside the region are increasingly seeking to build their economic and military ties with Red Sea countries, particularly those that control the most strategically vital locations. For instance, Russia and China are moving into various Red Sea ports, and Beijing has even established one of its few foreign military bases in Djibouti. Yet Washington is constrained because of the seam that separates U.S. military areas of responsibility along the Red Sea between CENTCOM and AFRICOM. Given the realities of geography, such seams will always exist, but they should be drawn in a manner that presents as few barriers as possible to working across separate areas of responsibility.

Susan L. Ziadeh

Dealing with cross-regional issues requires a high level of coordination and integration, so the U.S. government’s ineffectiveness in this regard represents an interagency problem. This problem has become particularly glaring because of the burgeoning relationships between East African and Persian Gulf countries, including non-littoral states. The number of African missions established in the Gulf has grown substantially, and vice versa; commercial flights between the two regions have increased as well. Gulf governments have significant interests in the East African countries lining the Red Sea coast, including investment opportunities, food security, chokepoint concerns, and regional projection of power.

Further abroad, China has become a major trade partner for Saudi Arabia and other Red Sea countries. Yet the United States still plays a key security role that Beijing is unlikely to step into anytime soon, if ever—especially vis-a-vis Iran, which remains a pressing concern for the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. U.S. officials therefore realize that these states will likely turn to Washington and China for different roles.

To address the lack of interagency coordination, one tactical recommendation is for the State Department’s Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs to post an Africa watcher in the Gulf—perhaps at the U.S. embassy in Abu Dhabi, where a large number of African missions are located. The Bureau of African Affairs could replicate this move by stationing a GCC watcher in Africa.

Creating a “special envoy for the Red Sea region” might also help coordinate cross-regional issues, though this position would have to come with specific tasks and possibly a time limit to avoid becoming self-perpetuating. Any such envoy would also need an interagency group in order to reflect a whole-of-government approach.

Tibor Nagy

At present, the U.S. government bureaucracy seems institutionally incapable of handling such cross-regional issues. At the State Department, for instance, many issues on the Africa Bureau’s radar have not been prioritized in the Near East Bureau. These problems are systemic and long-term, so they must be addressed accordingly—they cannot be solved transactionally or on an ad hoc basis.

A special envoy is not the answer either. Besides the fact that these very complicated institutional issues will require a great deal of time to resolve, appointing an envoy can leave heads of state confused as to who represents Washington: the U.S. ambassador to their country, or the envoy who visits occasionally. A better approach is to hand this portfolio to a senior official in the office of the undersecretary of state for political affairs, who is responsible for all regions of the world.

Regarding China, asking Red Sea states to side with Washington or Beijing will not work—these countries can now choose which partner is best for individual initiatives. Yet the United States can compete through private-sector investment.

Elana DeLozier

The scramble is on for footholds in the Red Sea, with various regional and international actors vying for influence in the littoral states. This is largely due to the economic growth in these states, several of which are experiencing high growth in GDP and population. With improved infrastructure, they can become an emerging consumer market.

Yet the region also suffers from political fragility and numerous security risks, including piracy, terrorism (in Yemen and Somalia), environmental issues (e.g., the FSO Safer oil vessel stranded in the Gulf of Aden), and threats to undersea Internet cables, among others. And despite the impressive GDP growth, persistent economic issues are still driving citizens of some states to migrate across both coasts of the Red Sea.

The region has attempted to establish security cooperation via multilateral agreements or institutions, most notably the Red Sea Council launched by Saudi Arabia. Yet one key player—Israel—was not invited to join this council, and getting smaller states to sign on was difficult given their concerns about being drawn into broader regional conflicts (e.g., with Turkey or Iran).

Another crucial issue affecting the region is great-power competition. This can be a positive when it contributes to economic growth. For instance, China and Turkey are involved in various local infrastructure projects, while the United States participates through foreign direct investment. When it comes to bilateral cooperation, economic or otherwise, the Red Sea states believe that China, Russia, Turkey, the United States, and others are all valid options—they do not consider Beijing and Washington as exclusive rivals or feel the need to take sides. Yet competition between foreign actors can be harmful when their rivalries are played out at the local level, as happened when the rift between Qatar and other Gulf states affected Somalia. This is why Washington needs a more holistic approach, to take this wide array of Red Sea issues into account and deal with them more effectively across different institutional seams.

This summary was prepared by Amal Soukkarieh. The Policy Forum series is made possible through the generosity of the Florence and Robert Kaufman Family.