The Israeli leader showed himself capable of making bold policy reversals when he felt the country's welfare as a democratic Jewish state was at stake.

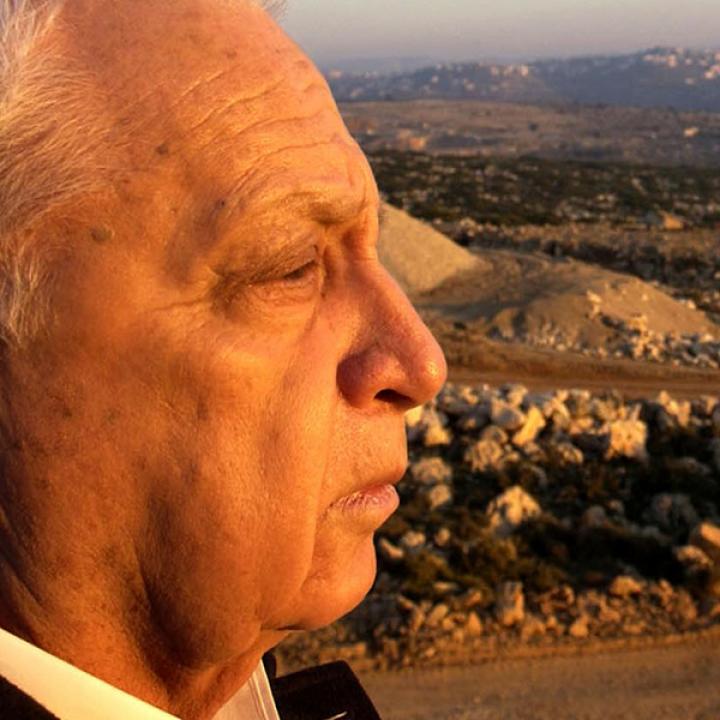

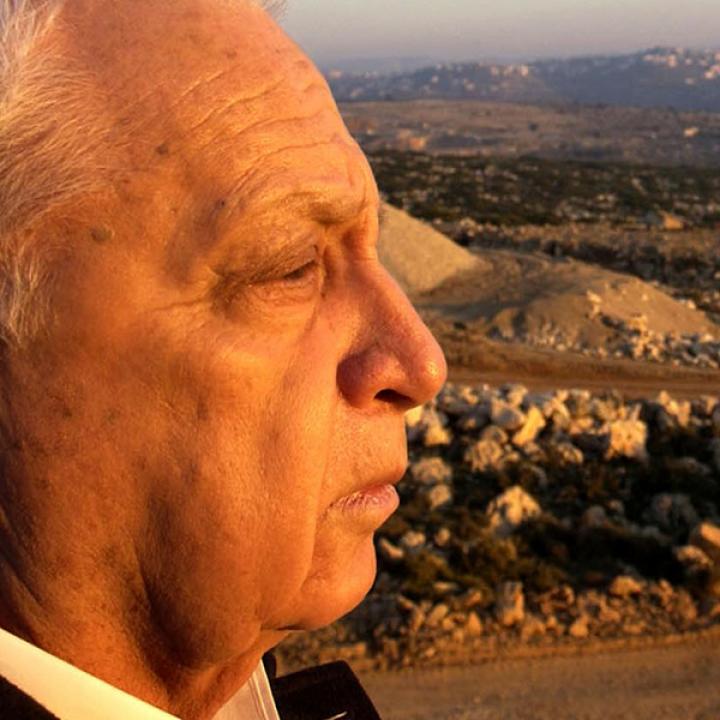

Former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon, at death's door today at age eighty-five after eight years in a stroke-induced coma, incarnated many of the contradictory dimensions of his entire country: courageous, and so unavoidably controversial; steadfast in his core convictions, yet flexible, impulsive, and even unpredictable in carrying them out; supremely self-confident, yet always acutely concerned about his country's security.

He rose to prominence, as the title of his 1989 autobiography succinctly notes, as a warrior: fighting with great ferocity and distinction in Israel's 1948 War of Independence, the 1956 Suez war, the 1967 Six Day War, and the 1973 Yom Kippur War; and then overseeing the 1982 Lebanon war, with a much murkier outcome, as minister of defense. But in his final years in political office as prime minister, even while ruthlessly and effectively striking back at Palestinian terrorists, Sharon demonstrated a very different side. He agreed to limit Israeli settlements in the West Bank, accepted the idea of an independent Palestinian state, and initiated the unilateral Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip. The contradiction, or at least irony, was merely a superficial one; for only a man with Sharon's unrivaled reputation for toughness could have pulled off such switches so successfully. That was when and why President George W. Bush famously, and correctly, called Sharon a "man of peace."

Even much earlier, from his first days as a military commander, Sharon was usually determined to go his own way, at times regardless of higher authorities far from the field. The results were decidedly mixed. He first earned attention as the spearhead of Israel's battle against Palestinian infiltrators, leading the unit that launched the bloody reprisal raid on the West Bank village of Qibya in 1953. He then led a costly and unnecessary commando raid, far into enemy territory, on the Mitla Pass in Sinai during the 1956 war. Yet he also led a brilliant counterattack, again far behind Egyptian lines, across the Suez Canal in the 1973 war. Although little remembered today, Sharon's division actually advanced to within about sixty miles of Cairo to turn the tide of war and contribute to an honorable ceasefire -- and ultimately to Egyptian-Israeli peace.

Yet a decade later on Israel's northern front, as defense minister during the 1982 war against the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Lebanon, Sharon ordered Israeli troops far beyond the initial forty-kilometer objective near the Litani River, all the way to the outskirts of Beirut. Prime Minister Menachem Begin, asked whether Sharon had misled him about the scope of this campaign, reportedly offered this laconic reply: "Well, Arik always tells me about his plans -- sometimes before, and sometimes after." The result was a brutal siege of Lebanon's capital city, which succeeded in expelling Arafat and the PLO but failed to crush their movement, or to reorder Lebanese politics to Israel's advantage. Quite the contrary; this Lebanon war left Israel with a new and more dangerous enemy: Hezbollah.

The Lebanon war also left a large stain on Sharon's reputation, because of the large death toll, culminating in the massacre of Palestinian refugees in the Sabra and Shatila camps around Beirut. All through his career, Sharon was tagged with leading military operations that inflicted civilian casualties, sometimes disproportionately. But this charge was misplaced. It was not Israelis, but Lebanese Phalangist militiamen, who murdered the Palestinians in those camps. An official Israeli commission of inquiry nevertheless found Sharon "indirectly responsible," and he was forced to resign as defense minister, although he remained in the cabinet a while longer. But Time magazine charged that Sharon had actually "encouraged" the massacre -- featuring a cover illustration of a Jewish star dripping with blood -- even though Christian guerrillas had actually committed the crime. Against all the odds, Sharon sued the American magazine for libel -- and won a symbolic judgment in his favor.

Sharon's last military venture was much more successful, with favorable political results that continue to shape the prospects for Israeli-Palestinian peace talks to this very day. A man who began his political life as a protégé of David Ben-Gurion and then rose to influence under Begin finally achieved the pinnacle goal of sweeping Likud to electoral victory shortly after the failure in late 2000 of the second Camp David summit and the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising. New prime minister Sharon then conceived and led Operation Defensive Shield, a series of large-scale incursions to root out Palestinian terror cells from West Bank cities at the height of the second intifada, in 2002-2003. Once again there were wildly exaggerated media accounts of Israeli responsibility for massacres, most infamously in Jenin. The accusations were false; and despite all the naysayers inside and outside Israel, the military campaign largely succeeded.

This time Sharon followed up, not with a protracted reoccupation of Palestinian cities, but with the security barrier separating these cities from Israel and its own cities and settlements just to the west. The naysayers were proved wrong yet again; the barrier -- sometimes a wall, more often a fence -- has worked to stop terrorists. It literally reinforces the verbal calls to stop terrorism uttered by Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, who replaced Arafat even as the barrier was being built. And the dramatic decline in Palestinian terrorism produced by the barrier, IDF action, and cooperation with Palestinian security services is what has enabled Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, currently promoted by Secretary of State John Kerry, to resume, long after Sharon himself was struck down by the stroke that forced him from the political scene.

On a personal level, I recall the first time I met Ariel Sharon, and the lasting impression it produced of a man who could dream large and act accordingly, triumph over great adversity, and most of all, change course courageously as new circumstances required. In 1985, I sat with Sharon at one of his legendary, lavish private dinners. To my astonishment, he maintained at length that one million or more Jewish olim (immigrants) could quickly be brought to Israel from the Soviet Union -- and this was still at the height of the Cold War, before Gorbachev, and long before the collapse of communism and its notorious walls. I mentioned this prediction to a much more senior colleague, who called it fascinating but wildly implausible. And yet, within less than a decade, Sharon's dream of mass Soviet Jewish immigration came true.

Even more impressive to me, however, is the epilogue to this little story. At the time he made that rash but prescient prediction, Sharon explicitly intended it to rationalize Israel's continued hold over the West Bank and Gaza. Soviet Jewish immigration, he meant, would largely "solve" Israel's "demographic problem" of including so many Arabs within its expanded borders. He was the one, after all, who had driven the creation of Likud in 1973, and invested so heavily in Israeli settlements across the 1967 Green Line.

Yet many years later, when Sharon realized that this part of his dream was unrealistic, he reversed course and decided that for Israel's own sake, he had to uproot the settlements in Gaza -- along with four tiny, isolated West Bank settlements -- as he had at Yamit in Sinai for the sake of peace with Egypt in 1982. And for the sake of peace with the Palestinians, or at least separation from them, he had to build a wall dividing Israel from the West Bank, and concentrate further settlement only in the sliver of land around Jerusalem and Israel's "narrow waist" near the Mediterranean coast -- precisely the area that Palestinians and other Arabs have finally agreed could be swapped to Israel as part of a final peace agreement with a Palestinian state.

In order to accomplish this historic reversal, Sharon had to make one last military-style surprise maneuver, but in the political arena. That was his bold decision to break from Likud and form his own party, Kadima, to oversee the planned withdrawal from Gaza and the further concessions to come. Critics of some of these steps, including myself, fault Sharon not for pulling out of Gaza but for doing so unilaterally instead of by agreement with the Palestinian Authority. This arguably gave Hamas an advantage there that it has retained ever since, albeit more precariously now. Perhaps Sharon did not fully realize, back in 2005, that he could try to make a deal with the newly installed and untested Abbas, rather than with the tested-and-proved-untrustworthy Arafat. For his part, Sharon argued that he could not let any Palestinian leader determine whether Israel would remain both Jewish and democratic.

That is an important detail, but a detail nonetheless. The larger point is that Sharon, and almost certainly only Sharon, could get Israel out of Gaza. The Israeli public trusted him to take care of all that, giving Kadima a solid vote of confidence in what turned out to be Sharon's last electoral campaign. It is a measure of Sharon's personal political power and credibility that, without him, Kadima has virtually disappeared from the Israeli political map.

And so, to the last, Sharon was decisive -- and therefore also divisive. With leadership, of course, comes controversy. Given all these seemingly contradictory twists and turns, what really is Sharon's legacy? His own career trajectory sums it up well: first be a fearsome warrior, in order to turn later to the work of peace. Because of this legacy, Israel today can contemplate its future more confidently, even as the region all around it implodes, or explodes. Whether that national confidence produces a new paragon of personal courage and political decisiveness in the spirit of Ariel Sharon is still an open question.

David Pollock is the Kaufman Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of Fikra Forum.