- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3072

For Assad, Manbij Is the Key to East Syria

Reestablishing control in Manbij is the only way to build influence across the Euphrates, and now that U.S. troops are set to leave, both Russia and local Arab tribes may support this regime goal.

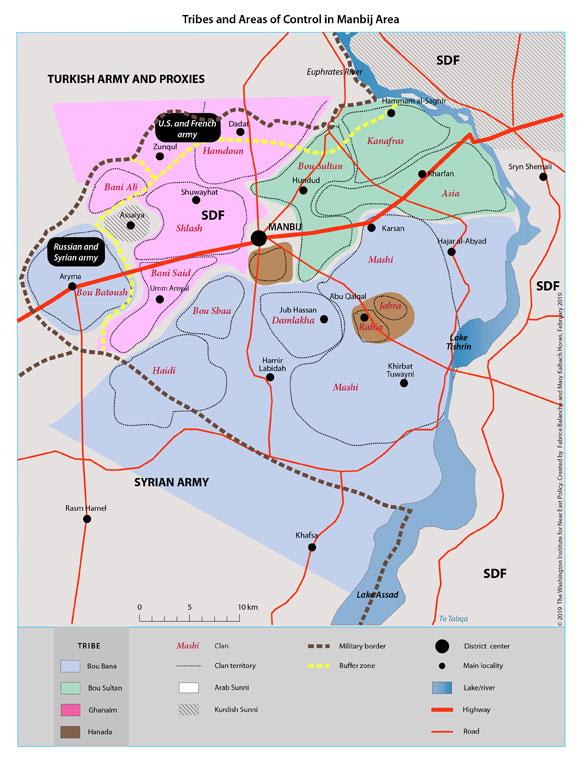

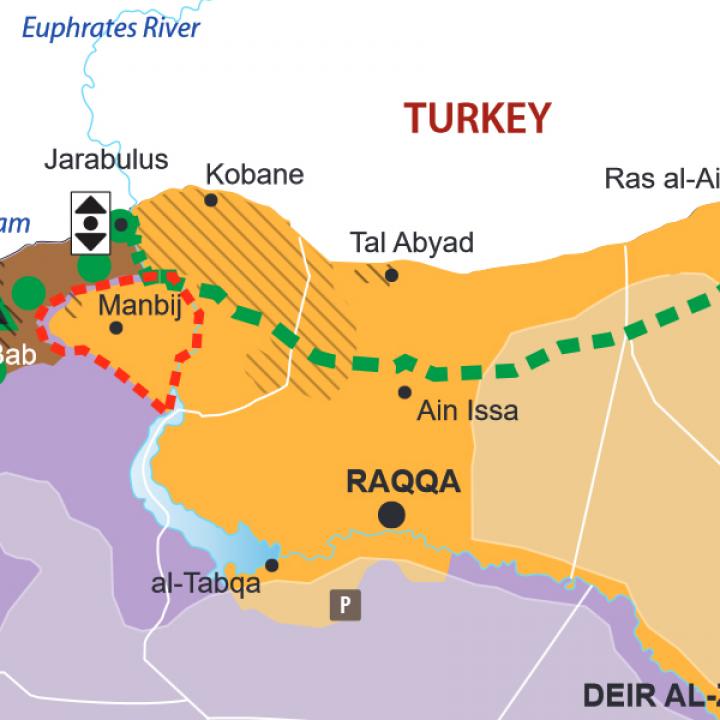

Click on maps for higher-resolution versions.

The terrorist attack that killed four Americans in Manbij on January 16 put the spotlight back on this crucial territory in north central Syria, where U.S. and French troops have been stationed to prevent a Turkish offensive against the Kurdish-led Syrian Defense Forces. By month’s end, however, Russian and SDF troops were carrying out joint patrols on certain local roads typically used by international coalition forces. Is this a prelude to the Assad regime’s return?

Since the Trump administration announced that it would be withdrawing all U.S. forces from Syria, the country’s northern frontier has become the subject of major haggling between Russia, Turkey, and Iran. Ankara is reportedly eager to seize Manbij, but Moscow seems to strongly oppose this outcome. As the tough negotiations play out behind closed doors, it is instructive to take a closer look at the geography and dynamics around Manbij in order to better understand what is most likely to happen there.

ARAB TRIBAL TERRITORY WITH A KURDISH MINORITY

The 500 square miles that comprise Manbij and the surrounding countryside are currently home to around 450,000 inhabitants, 80 percent of whom are Sunni Arab. Kurds represent only 15 percent of the population, despite the predominance of Kurdish-led forces in the area. The remaining 5 percent consist of Turkmen and Circassian minorities. Similar demographics prevail in the city of Manbij: home to 120,000 inhabitants in 2011, its population has swollen to 200,000 with the influx of internally displaced persons, most of them Sunni Arabs from Aleppo province.

The Kurds in Manbij city are generally mixed with the Arab population. In the countryside, one can find a single fair-sized Kurdish pocket around the village of Assalya northwest of Manbij, but for the most part Kurds are scattered in small hamlets among predominantly Arab villages. In short, unlike Kobane and certain other parts of north Syria, Manbij is not a Kurdish bastion for the People’s Defense Units (YPG), the Kurdish armed group that heads the ethnically mixed SDF.

Arab tribal organization is powerful in the Manbij area, including in the city itself, where the majority of neighborhoods have a tribal identity. Four major tribes occupy the area: in numerical order, the Bou Bana, the Ghanaim, the Bou Sultan, and the Hanada. Each of these tribes is in turn divided into clans with tens of thousands of members.

The most powerful clan is the Mashi, which dominates the area’s top tribe, the Bou Bana. Muhammad Kheir al-Mashi is chief of the Bou Bana, a member of the Syrian parliament, and head of the Manbij tribal committee, formed in January 2018 to contest the Manbij Civil Council (MCC), considered a YPG puppet. Yet one of his relatives, Farouk al-Mashi, co-chairs the MCC’s legislative council and therefore works closely with the YPG. This divergence is characteristic of tribal policy throughout much of Syria.

The Mashi clan’s relationship with the regime has shown similar ambiguities, often shifting with the tide of war. Its militia sought to repress the uprising against Bashar al-Assad in 2011, but when regime forces left Manbij a year later, it joined the rebel Free Syrian Army (FSA), taking the name Jund al-Haramayn. Later, the militia officially joined the SDF. More recently, however, the clan has become publicly close with the regime once again; for example, when its leader attended the Sochi peace conference in January 2018, he went as part of the “government delegation.”

The Ghanaim is the second most prominent tribe in the area. It was led by the Shlash clan for much of the war, but the family’s fortunes have been declining in recent years. Clan leader Ibrahim Shlash was a member of the MCC’s executive council when he was assassinated in July 2017, with the Islamic State claiming responsibility. The incident was comparable to the fate of Omar Alloush, the Raqqa reconciliation committee member who was killed last March, allegedly for being too close to Kurdish authorities. Some locals suspect that Turkey, the Assad regime, or other elements could be responsible for both assassinations, but no hard evidence has surfaced to back such claims.

Whatever the case, another clan has sought to take advantage of the weakened Shlash since the 2017 murder. The Bani Said hope to emancipate themselves from Shlash dominance by claiming that they are a tribe (qabilah) in their own right rather than just a clan (ashira). They may also intend to strengthen their opposition to the MCC as a way of challenging Slash leadership.

As for the Hanada and Bou Sultan tribes, both are following Muhammad Kheir al-Mashi’s lead in opposing the MCC. The Bou Sultan also have a land dispute with the Kurds on the east bank of the Euphrates River, giving them another reason to stand against the MCC.

ANTI-YPG SENTIMENT IS STOKING PRO-REGIME VIEWS

In general, local Arab sentiment in the Manbij area seems to favor YPG withdrawal and the return of regime control. This tentative conclusion is based on the author’s interviews with numerous Arabs from different social classes and tribes over the past year, both in person and over the phone. Any such conclusions are necessarily speculative given the lack of rigorous polling data in north Syria, not to mention the fact that local attitudes tend to change in accordance with conditions on the ground. Yet anecdotal reporting still holds significant value for those aiming to forecast the near-term future of Manbij.

Until recently, a minority of interviewees expected the establishment of an autonomous region in the north supported by Western forces. Following the U.S. withdrawal announcement, however, they have largely lost hope for that result and sided with the majority who favor the regime’s return. Certainly, some Arab locals are more hesitant on this matter, particularly young men who would be subject to regime conscription and activists who participated in the 2011-2012 uprising—most prominently Ibrahim Kaftan, president of the MCC’s executive council. But such individuals appear to be in the minority.

As for local Kurdish residents, they tend to avoid declaring their opinion because they are accustomed to living as a minority in Manbij and seemingly want to keep it that way. If by chance they were assimilated into the YPG, they would likely be obliged to follow it if it withdraws. These residents should be differentiated from the Kurdish leaders who control Manbij, most of whom hail from elsewhere in north Syria (e.g., Kobane or Qamishli).

This apparent dynamic—anti-YPG and anti-Kurdish sentiment spurring local Arabs to favor the regime’s return—is similar to that seen in the northern border district of Tal Abyad. The economic situation in Manbij is not appreciably worse than in regime-held portions of the country, but public services are much poorer, with many locals complaining about the educational and health systems in particular. Manbij residents are also very disappointed about the lack of Western humanitarian assistance.

As for non-YPG alternatives to regime control, many locals view them with great skepticism. The Turkish protectorate option is largely rejected because Manbij residents have been badly misinformed about the security and economic situation in other areas where that model has been implemented (e.g., Jarabulus and al-Bab). The prospect of the FSA returning under the banner of the Turkish-created Syrian National Army does not reassure them either; many interviewees described the previous period of FSA control over Manbij as a time of anarchy, racketeering, kidnapping, and other ills.

ASSAD NEEDS MANBIJ

A few days after President Trump’s December withdrawal announcement, the Syrian national flag was hoisted in the suburbs of Manbij, seemingly reflecting the strong presence of pro-regime militants in the area and their ties with local tribes. Indeed, the loyalty of Arab fighters in the SDF remains with their tribes, not with their YPG commanders or the MCC. They will not fight the Syrian or Turkish army to keep Manbij in Kurdish hands. Once international coalition troops withdraw, Assad’s forces should therefore be able to reoccupy the territory easily. To be sure, the United States might still decide to hand the keys over to Turkey, but the recent SDF-Russian patrols in northern Manbij suggest that this option is obsolete—Moscow may now want Manbij for Assad, not for Ankara.

This outcome is vital for Assad, who must prove to the local notables who back him that he is able to fulfill his commitments. This would in turn send a strong signal to tribal leaders and Arab residents east of the Euphrates who are still reluctant to pledge allegiance to him. In contrast, Turkish occupation of Manbij would be a grave humiliation for him, likely spurring the tribes to wait for Ankara to rid them of YPG domination instead. This is why Russia has been sending troops to Manbij and strongly opposing a Turkish offensive there, contrary to its support for the past Turkish intervention in Afrin.

Fabrice Balanche is an assistant professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, and author of the 2018 Washington Institute monograph Sectarianism in Syria's Civil War: A Geopolitical Study.