- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3843

Avoiding a West Bank Explosion During Ramadan

From al-Aqsa Mosque to the heart of the refugee camps and the barracks of frustrated Palestinian security personnel, the situation remains tense and could worsen dramatically this month if authorities do not tread carefully.

As the Muslim holy month of Ramadan commences on March 10, Israel and the Palestinian Authority will both need to take proactive measures that reduce the potential for escalation. This includes avoiding missteps that provide extremists, especially Hamas commander Yahya al-Sinwar, with an opportunity to unify “all Palestinian fronts” and turn the West Bank and Jerusalem into a new theater of the Hamas-Israel war. How exactly might bad actors exploit the situation? And what should Israeli, Palestinian, and foreign officials do—and, just as important, not do—to counter these efforts?

Hamas Signaling Ramadan Escalation

Recently, Hamas and other “resistance” players have stepped up their campaign to advance both the Palestinian national narrative and the religious narrative of “defending al-Aqsa” from the Jews. In this regard, Sinwar has clear precedents to draw from. In 2017, Israel installed metal detectors at the entrances to the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif, turning security clashes with Palestinians into a crisis with the wider Muslim world. And in May 2021, Gaza terrorists launched rockets from the Strip toward Jerusalem with the declared aim of “defending al-Aqsa,” sparking escalation in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and even Arab Israeli communities. Israel was soon dragged into another major military operation as a result.

Hamas has tried similar incitement tactics during the current war. In response, most Palestinians in the West Bank have stayed on the fence so far and refrained from violence. Yet the situation on the ground has grown increasingly fragile for months, and the wrong spark during Ramadan could turn the West Bank into a third front for Israel, joining Gaza and the Lebanese front. Sinwar is not the only one calling for such action—Hamas political chief Ismail Haniyeh has exhorted Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem to march to al-Aqsa Mosque on the first day of Ramadan and break the Israeli “siege.”

A Closer Look at the West Bank’s Fragile Reality

Ramadan tensions come at a time of rising Palestinian anger toward Israel across the West Bank. In part, this is because the Hamas-Israel war has damaged both the Palestinian Authority’s financial coffers and the wider economic situation. For months, Israel has withheld much of the clearance revenue it collects on the PA’s behalf, while the roughly 150,000 Palestinians who used to work in Israel have not been permitted to return during the war. As a result, unemployment in the West Bank now stands at 29%, compared to 13% prewar. In the fourth quarter of 2023 alone, the territory’s GDP dropped by 22%.

Ramadan is likely to underscore the worsening economy. Typically, consumer activity in the West Bank increases ahead of the holiday, but this year has seen a noticeable decrease in private consumption amid rising prices and scarcity in local markets—and, tellingly, an increase in bounced checks.

Meanwhile, some PA agencies have recently cut their operations to just two or three days per week because they lack the funds to pay public employees their full salary. In November, civil servants in the West Bank received 65% of their salary, up slightly from 50% in October.

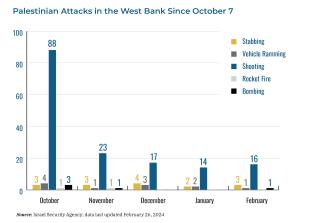

The security situation remains fragile as well. The Gaza war has inspired 180 significant Palestinian attacks in the West Bank since October 7, most of them shootings. Seventeen Israelis have been killed in these attacks. Although these incidents have decreased since their peak at the beginning of the war, Hamas and Iran are steadily trying to smuggle more weapons and explosives into the West Bank through Jordan, providing the tools for even greater violence.

Of course, the West Bank security situation has not been calm for a long time. Pockets of anarchy and terrorism were evident many months before the war, giving operatives a launchpad for attacks against Israeli civilian targets. Another terrorist focal point has been the refugee camps, where networks of Hamas, Fatah, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad operatives frequently target Israel Defense Forces (IDF) personnel conducting arrests or other security operations.

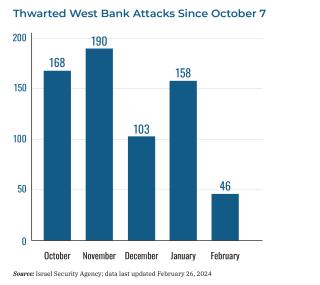

Since December, Israel’s decision to “take off the gloves” against these groups has significantly reduced the number of successful attacks. In all, the IDF has thwarted at least 665 significant attacks since October 7. PA security forces continue to operate against Hamas elements in the West Bank as well. Yet they have been forced to adopt a much lower profile amid the war, and their frustrations are mounting due to ongoing salary cuts.

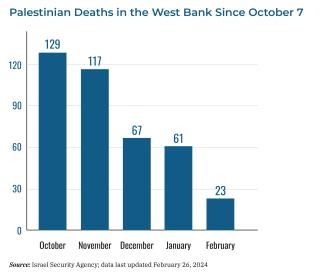

Moreover, thwarting attacks has come at the cost of dramatically increasing arrests. Around 3,300 Palestinians have been detained in the West Bank during the war, a process that inevitably increases friction between the IDF and the local population. Another consequence is higher casualties and a deepened sense of personal insecurity among Palestinian residents. Since October 7, about 400 West Bankers have been killed and another 4,550 injured.

Another factor in the West Bank security equation is the actions by a small group of extremists in the Israeli settler movement. Emboldened by the patronage of certain ministers and eager to respond to the announcement of U.S. sanctions against a handful of movement leaders, extremists have kept up their provocations against Palestinians in the West Bank. In the view of many Palestinians, Israel is using the cover of war to expand its settlements and outposts.

Prospects for Escalation in East Jerusalem

Heated wartime sentiments have likewise been swirling in East Jerusalem, especially amid Israel’s recent debate about restricting access to the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif during Ramadan. Yet here too, Palestinian residents have largely refrained from responding to Hamas’s calls for a mass uprising (though local perpetrators have carried out six significant attacks since October 7).

In deciding how to approach this population, authorities must remember that East Jerusalemites tend to identify as “defenders of al-Aqsa.” As such, they might join the violence at any time if sufficiently provoked—whether by Hamas’s ardent calls for Ramadan escalation, an Israeli attempt (real or perceived) to change the status quo at al-Aqsa, or an Israeli response to a provocation emanating from within the Haram itself. Even imposing Ramadan entry restrictions could spark a mass response—as Sheikh Kamal Khatib of the Israeli Arab Islamic Movement told Al Jazeera on February 20, such restrictions would be like “an earthquake” in the current climate, with unprecedented repercussions for the entire region. Thankfully, the Israeli government decided last week to impose cabinet control over access to the Haram during Ramadan, stripping National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir of that authority.

Policy Implications

From now until the close of Ramadan on April 9, numerous developments crucial to Israel’s national security could unfold, including a prisoner exchange with Hamas, a ceasefire in Gaza, a major IDF operation in Rafah, and possible escalation with Hezbollah. Adding a West Bank explosion to that pile would be dangerous, so Israel should be extra careful in its conduct over the next month. This means reducing tensions with the Palestinian public, deterring political or religious provocations by actors at home or abroad, and perhaps even postponing certain security measures if they do not seem worth the risk during Ramadan.

This approach is particularly important at the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif given the risk of dangerous blowups there. As part of this effort, close coordination between Israeli police in Jerusalem and the Jordanian-run religious foundation that administers the site (known as the Waqf) is essential. It is also important for outside actors—in Washington, Europe, and perhaps Arab capitals—to warn against the possibility of Hamas and other extremists exploiting Ramadan sensitivities to escalate tensions and provoke violence.

Appropriate action on the economic file is important as well, both to reduce local tensions and to prevent a wider PA economic collapse. Specifically, it would be wise for Israel to reconsider two of its wartime policies: withholding tax revenue it collects for the PA and barring virtually all Palestinian laborers from entering Israel for work.

On the security front, the low-profile but essential efforts by the PA security apparatus to prevent terrorism deserve recognition and support. Officials should not forget how useful this activity is in terms of saving lives, even when it is carried out more quietly than normal.

Finally, the diplomatic angle needs the right mix of attention and caution as well. Palestinians in the West Bank have become more pessimistic over the years about the chances for real change in their political and economic status, and few of them still believe that the United States or Israel will be the actors who bring this change. In contrast, Hamas’s October 7 attack, combined with Israel’s growing international isolation and the group’s ability to withstand months of IDF counterattacks, has fed expectations among many Palestinians that armed struggle rather than diplomacy might be the path to achieving their national aspirations. In this context, it is important for Israel to project a positive formula for eventual resolution of the Palestinian issue, perhaps by responding flexibly to American diplomatic proposals. At some point, the absence of any political pathway may generate sufficient disappointment to move West Bankers off the fence and into violent activism.

Neomi Neumann is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute and former head of the research unit at the Israel Security Agency.