Some countries banned the film while others let it screen amid restrictions and criticism, illustrating the region’s widening—but still comparably narrow—spectrum of views on cultural openness.

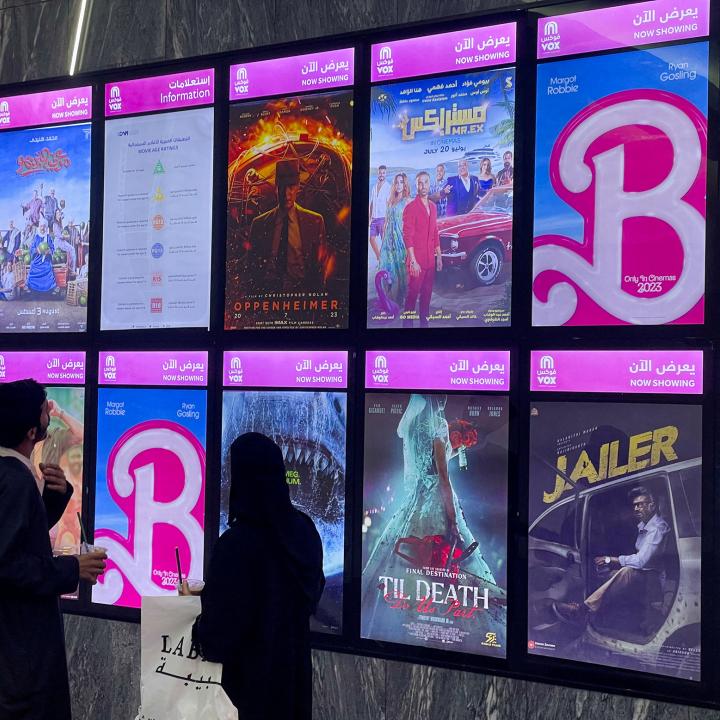

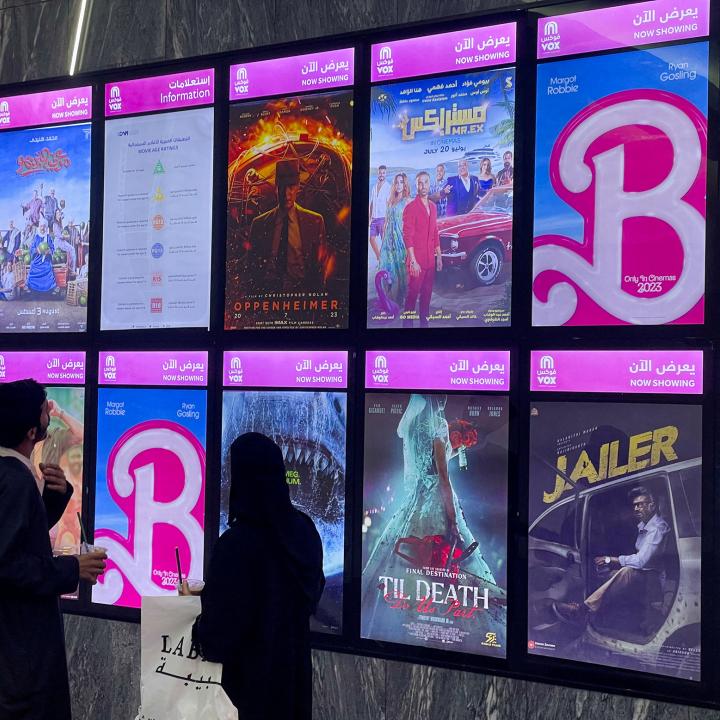

Not all audiences in the Middle East have had equal access to the summer blockbuster Barbie. When the Greta Gerwig-directed film hit theaters in late July, only two Arab countries—Morocco and Tunisia—shared in the premiere. Elsewhere, censors delayed the release, with the key markets of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates holding it until mid-August and Lebanon initially banning it outright because—in the words of Culture Minister Mohammad Mortada—it “promotes homosexuality and transsexuality...supports rejecting a father’s guardianship, undermines and ridicules the role of the mother, and questions the necessity of marriage and having a family.”

Curbs on Barbie are hardly surprising given the region’s history of censoring cinematic sexuality, LGBTQ themes, and other content seen to contradict local religious and cultural beliefs. The movie’s PG-13 rating, relatively tame treatment of sexuality, and absence of overtly LGBTQ characters did little to assuage the censors, who were likely unnerved by its female director and unflinching treatment of feminist issues. Arab female directors do, of course, exist, but their films rarely confront women’s issues so directly. The negative official reactions were also predictable given other recent restrictions on LGBTQ content, including the Saudi and Emirati ban on the PG-rated summer movie Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse for a scene featuring a transgender flag in the background.

Where Barbie Was Delayed

Besides Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, other governments that held up the film’s release until August included Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, and Qatar. All of them had initially announced August 30 as their target date, but their reasons for delaying release until then stemmed from concerns over the film’s content rather than any distributor issues. Vox Cinema, the local distribution partner for Warner Bros., negotiated with censors over possible cuts. In the end, they reportedly refrained from removing any major material, even allowing scenes with transgender actress Hari Nef to pass and preserving a faithful translation of the word “patriarchy.” Yet certain regional agencies assigned a more restrictive rating—Plus-18 in Egypt, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia, rendering it inaccessible to underage viewers, and Plus-15 in the UAE.

The film is nevertheless a smash hit in Saudi Arabia, where movie theaters were outlawed as recently as 2018. The kingdom had banned previous straight-to-DVD Barbie movies for portraying equal gender roles. Over the past month, however, Saudi women could be seen posting images of themselves clad in pink while driving to see the new movie, while restaurants in Riyadh introduced Barbie-inspired menu items. The film’s success reinforces the notion that Saudi society is gradually liberalizing and quite hungry for Western content.

The Emirati response has been similarly exultant. According to local chain Roxy Cinemas, the film “broke all records” in ticket sales, with showings scheduled every half-hour shortly after release. Emirati “Barbie-mania” has included lists of where to find related fare throughout Dubai.

Indeed, much of the region’s public response contrasts sharply with the official response. News coverage has highlighted enthusiastic praise from moviegoers, especially young women, one of whom said, “This movie is exactly what we needed right now.” Grassroots backlash has been limited, with the usual suspects—such as Jordan’s Islamic Action Front and hardline Bahraini cleric Hassan al-Husseini—unsurprisingly venting their condemnation. Some of the film’s themes faced similar criticisms in the United States, but the fact that certain Middle Eastern governments were willing to permit screenings and public debate about these issues is a revealing shift in their approach to cultural trends they may have previously deemed threatening.

Where Barbie Was Banned

Kuwait and Oman prohibited the film entirely, while Algeria removed it from theaters after it premiered and Lebanon agreed to screen it after an initial ban. In Kuwait, the state-run news agency argued that the film presented “ideas and beliefs that are alien to the Kuwaiti society and public order.” Residents have nevertheless found ways around the ban, such as pirating the film using tips from sites like Reddit or crossing the border into Saudi Arabia—a highly ironic twist given that Saudis had to make the reverse journey in past years if they wanted to watch movies on the big screen.

Oman’s ban came without official explanation. Yet media reports indicate that the government based its decision on scenes it deemed “unsuitable for children, such as drug use or other illicit content.”

Algerian authorities banned the movie after it had already been showing across the country for weeks. The Ministry of Culture, which usually announces censorship information prior to a movie’s premiere, has offered no comment as of this writing. According to one media report, authorities belatedly concluded that the film “promotes homosexuality and other Western deviances” and “does not comply with Algeria’s religious and cultural beliefs.”

In Lebanon, some officials evidently sought to prohibit the film for its LGBTQ themes and presentation of marriage and family, echoing the rise in anti-LGBTQ sentiment propagated by Iran-backed Hezbollah, which controls much of the government. On September 1, however, the General Security Directorate released a decision allowing the film to be shown.

Anna Brown is the media relations associate at The Washington Institute.