- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

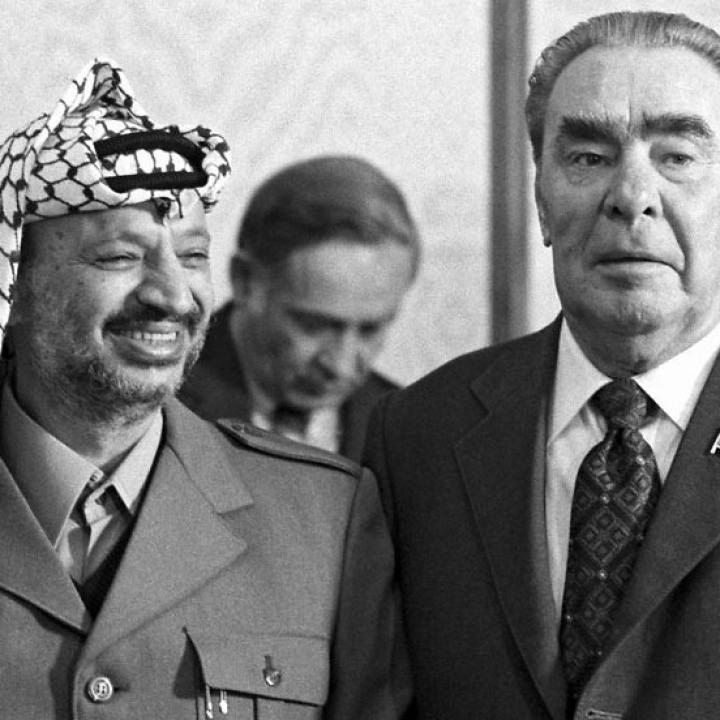

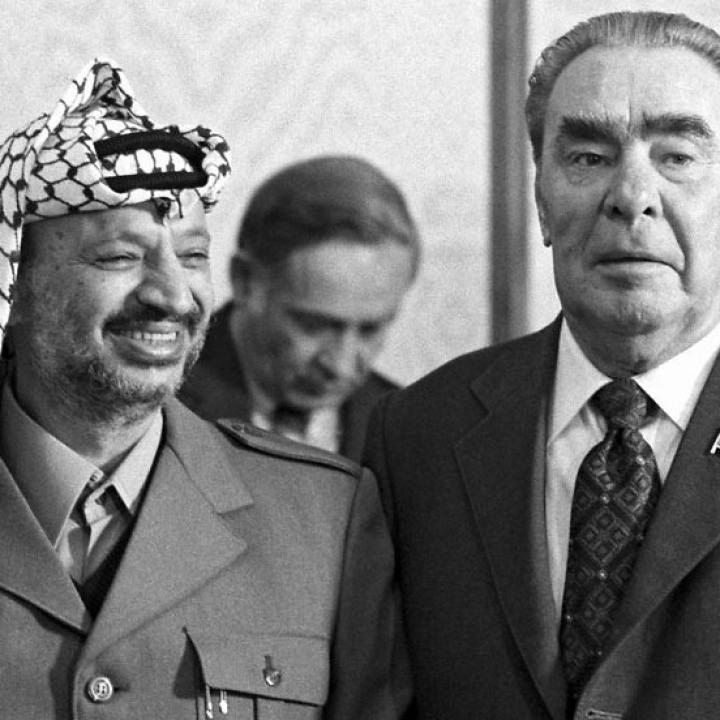

Book Review: The Soviet-Israeli War, 1967-1973

New evidence sheds light on Soviet involvement in Egypt and helps frame Vladimir Putin’s current efforts in the Middle East.

Conventional wisdom holds that the U.S. policy of detente restrained the Soviet Union in the Middle East, including in Egypt. This perspective also holds that Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s expulsion of thousands of Soviet military advisors in July 1972 was a major Soviet Cold War defeat. In their book The Soviet-Israeli War, 1967-1973: The USSR’s Military Intervention in the Egyptian-Israeli Conflict (Oxford University Press, 2017), Isabella Ginor and Gideon Remez challenge these fundamental concepts. The authors argue that, far from being a source of moderation, the Kremlin aggressively encouraged and enabled Egypt to challenge Israel.

They maintain that Sadat’s expulsion of Soviet advisors (who in fact fought alongside the Egyptian army) was a skillful deception because the Soviets never truly left. As Egyptian Maj.-Gen. Adel Suleiman Yusry recounted twenty-five years later, “‘the most effect[ive] part’ of Sadat’s deception moves was ‘his renunciation of Soviet advisors and experts. This deceived both Israel and the USA, which concluded that under the conditions thus created, a military solution to the Middle Eastern problem was hardly possible.’”

Ginor and Remez dissect traditional sources such as Henry Kissinger’s memoirs and find them misleading and self-serving. The authors also find contemporary newspaper accounts inadequate since during “most of the period in question, there was no American and little Western press presence in Egypt; none of either in the combat zone.” They also argue that the Kremlin often did not document key meetings. Archival documents alone are thus inadequate and also remain largely unavailable, especially given renewed intense censorship in Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Instead, they rely on newly available sources including interviews, memoirs, journals, and testimony from Soviet soldiers on the ground. The authors thoroughly cross-check these against one another and against newly declassified American, Israeli, and other sources.

The full extent of Soviet involvement in 1973 is unknown, and the emerging record remains incomplete. But Ginor and Remez’s new evidence not only brings us closer to understanding history but helps frame Putin’s current involvement in the Middle East. Their focus on primary sources from Soviet veterans raises critical questions about previous ideas on the Soviets’ role in Egypt. Although the Soviet Union spoke of a desire for peace and stability in the Middle East, the Kremlin pursued a different agenda. Washington underestimated the Kremlin’s commitment to undermining it and its allies. Now as before, our knowledge of the Kremlin’s current activities in the region is incomplete, but as the authors note, “the sense of deja vu is overpowering.”

Middle East Quarterly