A veteran U.S. policymaker and two notable Iranian expatriates look back at forty years of fraught relations, discussing ways to advance American interests and reduce bilateral antagonism without letting human rights issues lapse.

On November 8, Stuart Eizenstat, Mehrangiz Kar, and Mehdi Khalaji addressed a Policy Forum at The Washington Institute. Eizenstat held senior positions in multiple U.S. administrations and authored the critically acclaimed book President Carter: The White House Years. Kar is a prominent Iranian attorney, human rights activist, and author. Khalaji is the Institute’s Libitzky Family Fellow. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

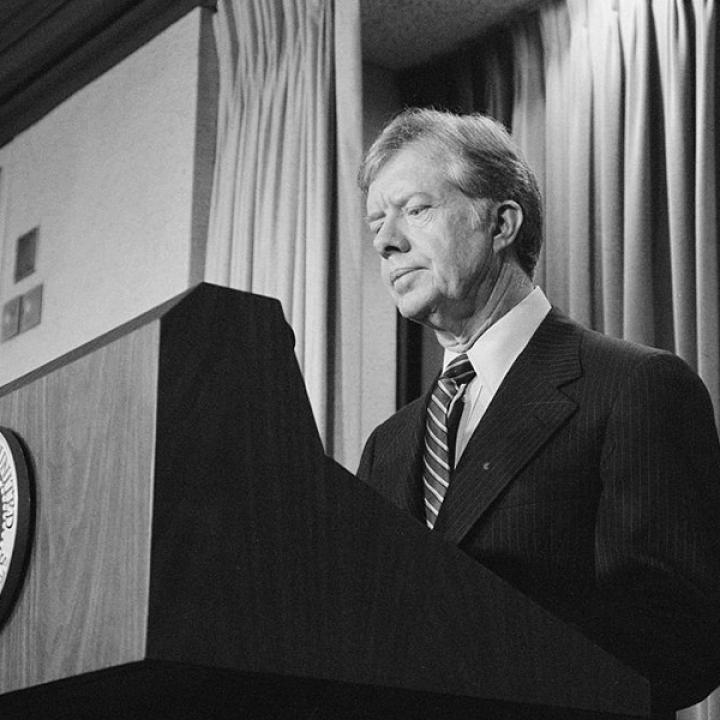

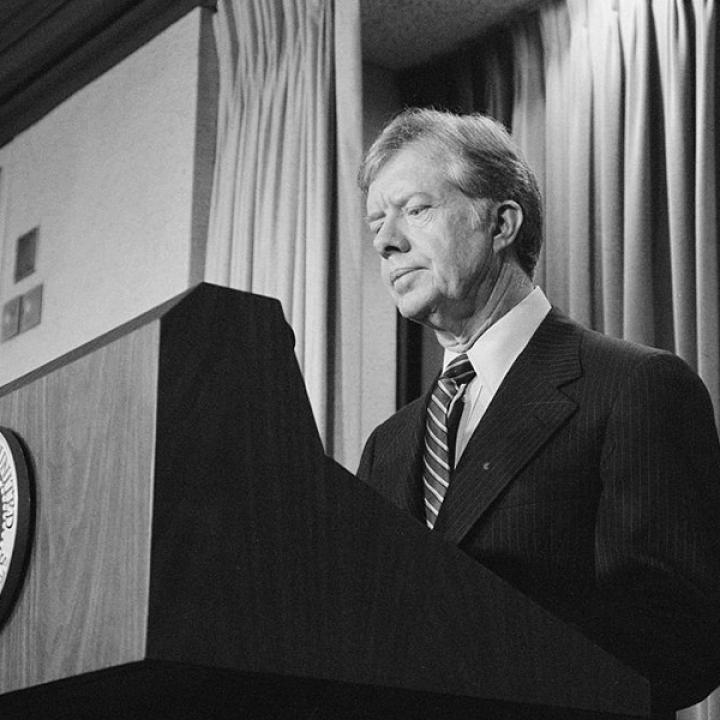

STUART EIZENSTAT

U.S. policy in the years leading up to the Iranian revolution rested in part on the single worst intelligence failure in American history. The United States did not have the on-the-ground information it needed to understand what was happening inside Iran.

At the time, the Carter administration was split between three different proposals on how to move forward in its relationship with Tehran. While Ambassador William Sullivan wrote a cable in 1978 calling for Washington to reach out to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance urged the shah to reach out to the nonviolent and non-fundamentalist opposition instead. For his part, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski advocated restoring order before pushing for reforms. These contradictions show that there are limits to how far the U.S. government can go in controlling political situations abroad when it suffers from intelligence failures.

Regarding sanctions, the United States has become much more effective at projecting financial power following two past pressure campaigns: one after the hostages were taken in 1979, and another by the Clinton administration. During the former campaign, Washington received virtually no support from its allies and had not yet begun using secondary sanctions. During the latter, secondary sanctions drastically improved Washington’s ability to influence Iranian commerce. Today, the international community is witnessing a third iteration: one in which American financial power is so far-reaching that it seems virtually inconceivable that any bank in the world would buck U.S. secondary sanctions. The latest financial campaign will be much more effective, and the pain on Iran will be severe.

The Obama administration applied this type of pressure ahead of the 2015 nuclear deal. Yet when Washington relied on unilateral sanctions alone, Tehran did not budge—the regime came to the table only after the administration convinced the European Union to halt oil imports from Iran, sanction the Central Bank, and bar the SWIFT network from clearing Iranian financial transactions. If Washington can reestablish this multilateral front today, it would have more success in forcing Iran back to the negotiating table.

In light of the Trump administration’s strategy, the United States would have been better off remaining party to the nuclear deal, using it as a foundation for cooperation with Europe in confronting Iran’s other malign behavior. In any case, the need for tougher sanctions on Iran’s terror sponsorship, human rights abuses, and missile program persists. Washington should play an active role in pushing back against Tehran because the regime is a threat to both regional stability and America’s closest allies.

MEHRANGIZ KAR

Looking at Iran through the lens of the Cold War, one can understand why it was a closed society before the revolution. The shah was allied with the United States in opposing a serious threat to its immediate north, the Soviet Union. Even if he had wanted to bring about democracy in Iran, he would not have been able to institute full freedom of expression and similarly dramatic reforms in such an environment. Any change would have to be slow so as to avoid undue chaos. Despite this, he invited disorder in 1978 by permitting a rapid opening within society.

Months after the revolution, the hostage crisis broke out, splitting the opposition to the shah. One faction was embarrassed by the incident and hoped Washington would take action to weaken the new regime. This faction was convinced that a great power such as the United States would place great importance on freeing the hostages. Once it became clear that Washington would not take prompt action, the regime became more confident about continuing its behavior. Not only did this inaction consolidate and embolden the regime, it also crushed the hopes of Iranians who rejected extremism, demonstrating just how profound an impact the United States can have even through its mistakes.

Today’s Iran resembles none of the ideals inherent to open societies. The regime faces no threat of invasion as it did under the shah, yet it still asserts itself abroad while brutally stamping out dissent at home. Yet the country is more open today in some respects. Social change and ever-increasing access to social media have made Iranian society far more capable of rapid change. In other words, such change would be far less destabilizing today than it was under the shah.

MEHDI KHALAJI

Despite the shah’s shortcomings, there is no comparison between his rule and that of the Islamic Republic. For example, statistics indicate that around 3,000 Iranians were killed for political reasons during the shah’s twenty-seven years in power. Yet the Islamic Republic killed more than 5,000 prisoners in the summer of 1988 alone.

Today, the lack of a clear political alternative and the traumatic experience of 1979 make another revolution unlikely in the near future. A recent poll conducted by a political reformist revealed that roughly 85 percent of Iranians have no hope in the government.

Even so, drastic changes are occurring in Iranian attitudes, particularly on women’s rights and religion. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Middle East witnessed the rise of Islamism, but today’s Iran is one of the most socially secular countries in the region. For example, statistics show that roughly 50 percent of Iranians do not fast—and have no problem demonstrating this refusal in public despite it being a criminal offense. The experience of life under the Islamic Republic is largely responsible for this social change, so the idea of regime change should be placed within this cultural context.

For now, the U.S. administration has made clear that its pressure campaign is geared toward bringing Tehran back to the negotiating table. Yet while this may compel the regime to compromise on some foreign policy issues, many Iranians feel that Washington does not care about their rights. As a result, they tend to have ambivalent feelings about U.S. policy: they want Tehran to curb its destabilizing behavior, but they do not want that shift to come at the cost of their human rights and their hopes for freedom.

Sanctions have become a sort of obsession in Washington today, but there are many other ways to pressure the regime, including effective public diplomacy. Washington’s broadcasting efforts in Iran are terrible and need to be fundamentally changed. For example, Voice of America has performed miserably in explaining U.S. policy to Iranians—part of a wider failure to use the political impact of sanctions as an avenue for promoting American values.

This summary was prepared by Arjan Ganji.