Close analysis of Iranian history textbooks indicates that not even the regime regards the 1953 coup as a seminal event in souring bilateral relations.

When discussing U.S. strategy to counter the threat of Iran, prominent U.S. lawmakers have stated that the regime’s behavior is an understandable demonstration of self-defense brought about by U.S. involvement in the 1953 coup that overthrew then-prime minister Muhammad Mossadeq. During a 2016 Democratic primary debate, Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-VT) characterized the regime’s fundamentalist nature as a reaction to the coup. Rep. Ron Paul (R-TX) similarly stated during a 2007 interview, “I see the Iranians as acting logically and defensively...We overthrew their government through the CIA in 1953.” In 2000, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright suggested that the coup justified the regime’s anti-American stance, saying, “It is easy to see now why many Iranians continue to resent this intervention by America in their internal affairs.”

Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has pushed this narrative multiple times as well. In a tweet comparing current U.S. sanctions to the 1953 coup, he stated that “an ‘Action Group’ dreams of doing the same [overthrowing Mossadeq] through pressure, misinformation, [and] demagoguery.”

Despite the prevalence of this notion, however, analysis of Iranian high school history textbooks shows that this narrative is not what the regime teaches Iranian students. Research for this piece included examination of state-issued eighth- and eleventh-grade textbooks from the 2019–20 academic year, which were available on the Iranian Ministry of Education’s website. Whether they attend private or public school, all Iranian students take the same history curriculum.

Iran’s history textbooks give a more complicated account of the 1953 coup, presenting it not solely as the result of foreign intervention, but rather as a consequence of weak government. Iran’s history curriculum does not assign a great deal of importance to Mossadeq, mentioning his role only briefly in eighth-grade textbooks and devoting only a couple paragraphs to him in eleventh-grade textbooks. In fact, his premiership is often criticized, and his importance often downplayed.

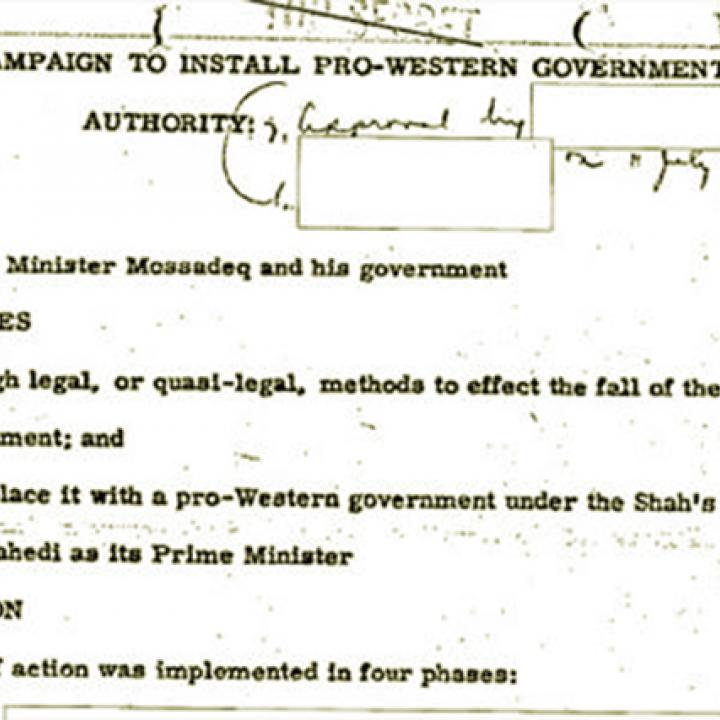

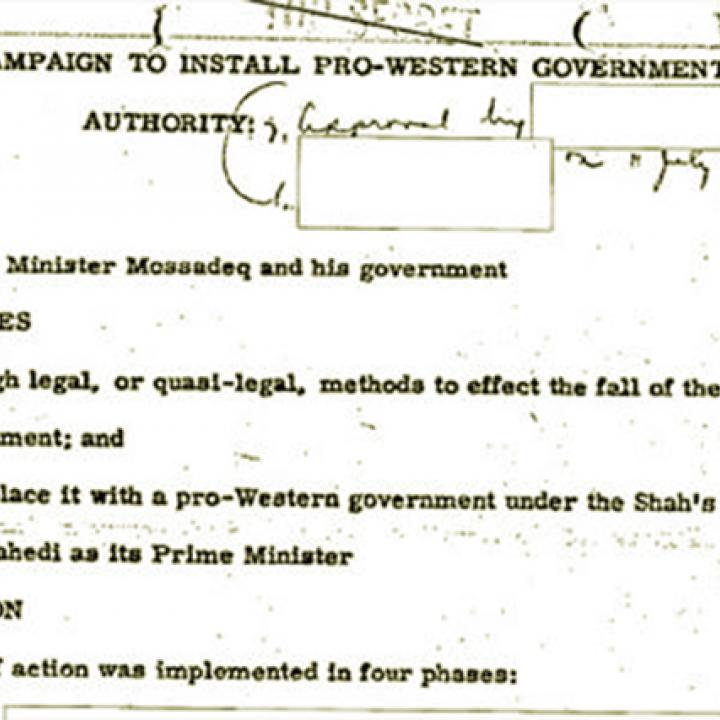

Mossadeq’s role in the nationalization of Iran’s oil, for example, is minimized in favor of Sayyed Abul Qassem Kashani, a distinguished Shia cleric, a mentor to future Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, and a prominent anti-Western, anti-capitalist voice. Furthermore, declassified documents have shown that Kashani was at times conspiring against Mossadeq with funding provided by the CIA.

With regard to Iran’s history of foreign interference, textbooks teach that Britain and the Soviet Union were the actors primarily responsible for the 1953 coup. At one point, the eleventh-grade books even say that the United States was “dragged” into the plot. This account would suggest that the regime does not want to teach children that the coup was merely a unilateral U.S. plot to interfere in Iran’s domestic affairs, but rather the result of a variety of factors that led to the removal of a secular leader.

Textbooks address the nationalization of oil and the 1953 coup in both eighth and eleventh grade, but a student’s focus on either the humanities or STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) determines the extent to which he or she is taught about this time in history. Humanities-focused history textbooks dedicate merely one short chapter to the subject, briefly discussing the Kashani-Mossadeq relationship, 30th of Tir Revolt, and British-American coup. But the eleventh-grade STEM-focused history textbook discusses oil nationalization and the coup in more detail, dedicating two chapters to the subjects. A four-page chapter briefly discusses Britain’s interest in preserving its stake in Iran’s oil production; it also touches on the leaders of the pro-nationalization movement, Kashani and Mossadeq. However, even here the chapter dedicates a mere brief paragraph to Mossadeq’s biography.

The STEM textbook’s chapter on the coup glorifies Kashani’s role, saying his return from exile in 1950 “boosted the anti-imperialism morale which urged the public to join the discourse,” and that his call for holy war in favor of Mossadeq and against his British-backed opponent, Ahmad Qavam, would enable Mossadeq to return to power. This take effectively downplays Mossadeq’s leadership in favor of extolling a religious leader’s wisdom and guidance.

Further, that same chapter partially blames Mossadeq for the coup itself, saying, “Against Kashani’s advice, Mossadeq used foreign interference as an excuse to dissolve the parliament. This empowered pro-coup activists, enabling them to argue that dissolving the parliament delegitimized Mossadeq’s government.”

Kashani would turn against Mossadeq in mid-1952, but the chapter does not provide a reason for their falling out. It does, however, vaguely list “disunity within the movement” as a key factor that led to the coup. Iranian students are taught that this “lack of cohesion” among the movement’s leadership is what enabled Britain to interfere with Iranian domestic politics, thus paving the way for continued foreign interference.

The chapter goes on to explain that a series of external and domestic factors led to the coup, all of which center around British and Soviet policies rather than those of the United States. Although those external factors included British and American agendas, the chapter suggests that London and Moscow persuaded the United States to change its stance on Iran: “Initially, the U.S. was seeking to mediate between Iran and Britain to prevent an economic crisis. Britain agreeing to include American companies in Iranian oil reserves and the rise of communism transformed U.S. foreign policy toward Iran.” The chapter continues, naming the activities of the BEDAMN intelligence network as yet another factor that led to the coup, characterizing it as “a British-founded intelligence network in Iran to counter the influence of the USSR,” without mentioning the United States.

The eleventh-grade STEM textbook also places a great deal of blame on the Tudeh Communist Party of Iran, stating that it supported Soviet interests. “The Tudeh Party only advocated for nationalizing Iran’s southern oil fields, as it saw the northern oil fields belonging to the USSR.” The chapter ends with a few summary questions on various domestic elements, then asks students about British efforts to weaken Mossadeq by persuading Washington to partner with London.

It is clear that Tehran is interested in teaching a narrative that portrays the infallibility of clerical leaders and thus the legitimacy of the current Islamic regime. At the same time, the government does not appear interested in teaching this part of history in great detail, much less in portraying it as the beginning of U.S. attempts to control Iran. After all, the leader of the Islamic Revolution, Ruhollah Khomeini, undermined Mossadeq’s role in Iranian politics, labeling him a “non-Muslim” in a 1981 speech.

In short, the driver of the regime’s anti-American sentiment cannot be the 1953 coup. If Tehran perceived Mossadeq’s overthrow as a key turning point in relations with Washington, it would be raising the third generation of the Islamic Revolution to believe in that notion.

Jonathan Sameyach is a researcher in the Viterbi Program on Iran and U.S. Policy at The Washington Institute. A refugee from Iran, he received a degree in political science from the University of California at Berkeley.