A demonize-and-polarize strategy has worked for the Turkish president in the past, but it may ultimately tear his country apart.

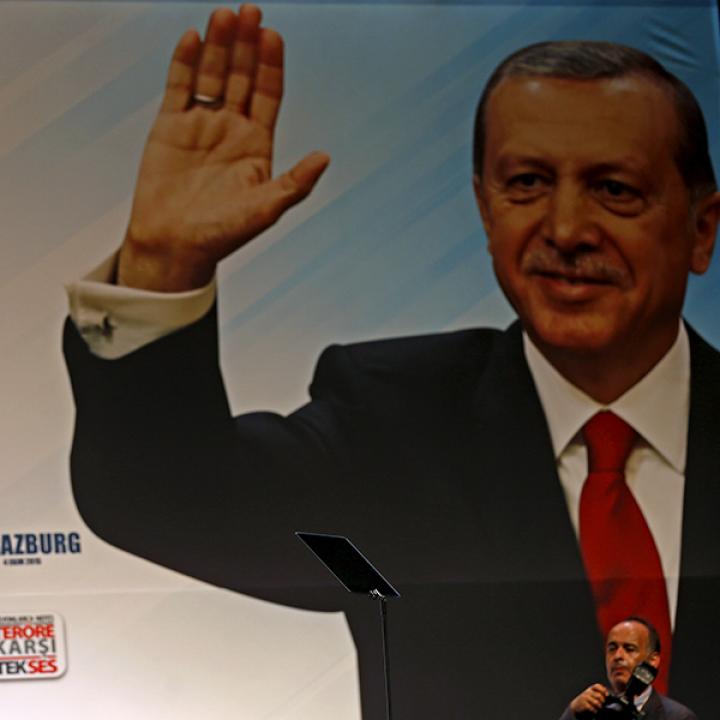

Since 2003, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been a guiding light for the ascendant global class of anti-elite, nationalist, conservative leaders. And all along, he has played the political underdog, rallying support by demonizing those who oppose him. Just weeks ahead of a constitutional referendum that, if passed, would further consolidate his authoritarian grip on the country, he has even taken to internationalizing this strategy, lashing out at various European leaders as "Nazis" for criticizing him.

It may be a reasonable gamble from his perspective; after all, it has brought him success in the past. He has boosted his popularity by relying on a steady supply of domestic adversaries to cast as the latest "enemy of the people." But this has also polarized his society to such an extent that even the security services, the traditional bulwark of Turkish unity, have become politicized and weakened at a time when the country faces violence on multiple fronts -- along with the implosion of Turkey's relationships in Europe. Amid a divisive campaign ahead of the April 16 referendum, terrorist groups ranging from the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) to the Islamic State exploit these divisions to turn Turks even more bitterly against each other.

Today, as evidenced by surveys measuring expected support for Erdogan in the referendum, Turkey is about evenly split between pro- and anti-Erdogan factions: the former, a conservative right-wing coalition, believes that Turkey is a paradise; the latter, a loose group of leftists, secularists, liberals, Alevis (liberal Muslims), and Kurds, think they live in hell.

For years, Turkey's vaunted national-security institutions, including the military and the police, had helped the country navigate its perilous political fissures, first in the civil war-like street clashes pitting the left against the right in the 1970s, and later in the full-blown Kurdish nationalist insurgency and terror attacks led by the PKK in the 1990s. However illiberal and brutal their methods, including several coups d'état and police crackdowns, the military and police kept Turkey from imploding. But this has changed since Erdogan's unprecedented purge of the security services in the aftermath of the failed coup of July 15.

At the same time, Turkey's involvement in the Syrian civil war is having unexpected, destabilizing repercussions back home, which are also severely undermining the country's ability to withstand societal polarization. Ankara has sought to oust the Assad regime since the outbreak of civil war in Syria in 2011. After sending troops into northern Syria in August 2016, Turkey has also conducted military operations against both ISIS and the Kurdish Party for Democratic Unity (PYD). Accordingly, Ankara now has the distinction of being hated by all major parties in the Syrian civil war -- Assad, ISIS, and the Kurds. Syria will no doubt continue trying to punish Turkish citizens for their country's actions: Turkey has blamed the Assad regime for a 2013 set of car bombings in Reyhanli, in the south of Turkey, that killed 51 people, though the Syrian government denied involvement.

Erdogan's Syria policy is also a driver of ISIS and PKK terror attacks in Turkey. Each time Ankara makes a gain against the PYD in Syria, the PKK targets Turkey. And each ISIS attack in Turkey similarly seems to be a direct response to a Turkish attack against jihadists across the border. For instance, the June 2016 ISIS attack on the Istanbul airport, which killed 45 people, occurred just after Ankara's Syrian-Arab proxies took territory from the terrorist group. The New Year's Eve attack on an Istanbul nightclub that claimed at least 39 victims came just as Turkey-backed forces launched a campaign to take the strategic Syrian city of al-Bab from ISIS.

ISIS and the PKK represent the extremes of Turkey's two halves, each intent on widening the country's political chasm -- a chasm that, in turn, prevents the country from holding a candid debate on its Syria policy, and that policy's impact on domestic security. Consider ISIS's chosen targets: venues like the nightclub, frequented by secular and liberal Turks; foreign tourists, who have been targeted in multiple attacks in Istanbul; Kurds and leftists like those killed in a July 2015 twin suicide bombing in the Turkish border town of Suruc; as well as liberal Muslim sects like the Alevis, a key bloc in the anti-Erdogan opposition and the main victims in the most devastating ISIS attack in Turkey to date, which killed 103 people at a peace rally in Ankara in October 2015.

By targeting foreigners and members of the anti-Erdogan bloc, ISIS seems to be sending a message to pro-Erdogan nationalists that the jihadists do not pose a danger to them -- that they are focused instead on "cleansing" the country of the kind of Western influence the Islamist government also sees as a threat. But as ISIS continues targeting Turkey's anti-Erdogan elements, the PKK and its offshoots will continue reciprocating. Kurdish militants routinely conduct deadly attacks on police and military forces. Their own message is to the country's anti-Erdogan bloc -- that as the Turkish leader consolidates his power, the PKK, however unpleasant, is their only hope against "Erdogan's troops."

Erdogan's policies may hasten this trend. At present, as seen in pro-Erdogan media, his government recognizes those killed by the PKK as "martyrs," granting them special status. He has so far refused to endow those killed by ISIS with such special recognition. Left unchanged, this policy could help create a two-tier taxonomy for deaths from terror attacks, further entrenching Turkey's divisions along a PKK-ISIS axis.

The failed coup, meanwhile, gave Erdogan license to consolidate power over the military and police forces, pulling them further onto the pro-Erdogan side of Turkey's divisions. The next time the military intervenes in politics in Turkey, it will probably not be to topple Erdogan, but to defend him. The 22-year-old man who assassinated the Russian ambassador in Ankara on December 19, a member of Ankara's elite police force who came of age in Erdogan's Turkey, is a sign of the politicization of the police forces as well as the consequences of Erdogan's Syria policy. This was an explicitly political murder: Before pulling the trigger, he declared he was punishing his victim for Moscow's policy in Syria.

For Erdogan, chaos may breed opportunity. If the constitutional referendum passes, it would vastly expand the powers of the office of the president, making Erdogan head of government, head of state, and head of his ruling AKP party, consolidating power over the entire country. (Currently, he is only head of state, and as such lacks de jure control over the government. The country's constitution also stipulates that the president be a nonpartisan figure, barring him from formally heading the ruling AKP.) But even if he does win, only half of the country will embrace his agenda. The other half will work to undermine it politically -- and in the case of the PKK and other leftist militant groups, violently.

Turkey is a country divided against itself. If terror attacks, societal polarization, and violence catapult it into an unfortunate civil war, the country will have no one to save it from itself.

Soner Cagaptay is the Beyer Family Fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute.

Atlantic