- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3192

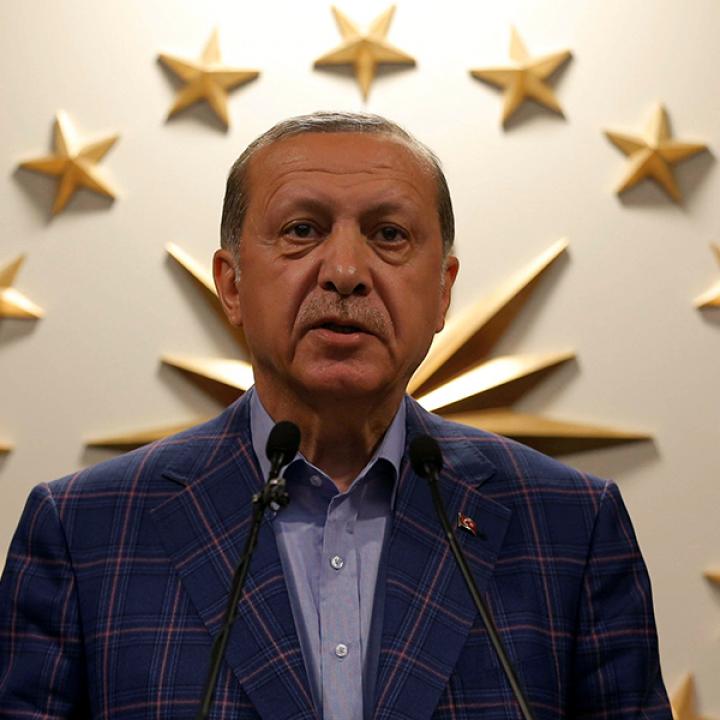

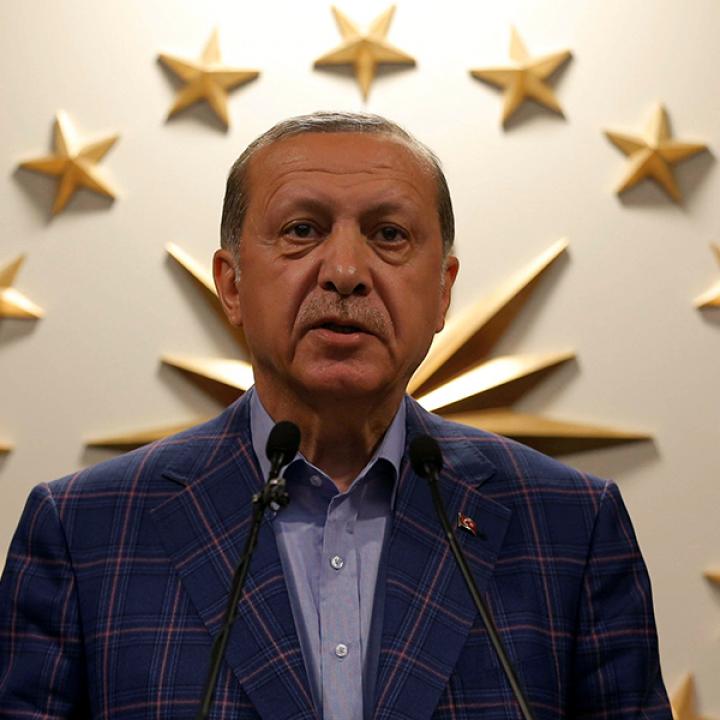

Erdogan's Empire: The Evolution of Turkish Foreign Policy

A lively discussion of how Ottoman history, pro-Western precedent, and sharp regional setbacks have shaped the Turkish leader's shifting approach to foreign affairs and relations with Washington.

On September 24, Soner Cagaptay, Amanda Sloat, Molly Montgomery, and Tomasz Hoskins addressed a Policy Forum at The Washington Institute to discuss Dr. Cagaptay’s new book Erdogan’s Empire: Turkey and the Politics of the Middle East. Cagaptay is the Institute’s Beyer Family Fellow and director of its Turkish Research Program. Sloat is a Robert Bosch Senior Fellow with the Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe. Montgomery is a vice president at Albright Stonebridge Group and a former State Department advisor. Hoskins is the publisher and commissioning editor for politics at I.B. Tauris, an imprint of Bloomsbury. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

SONER CAGAPTAY

Nations that were once great empires often have an inflated sense of their heyday, making their citizens easy to inspire with appeals to the past—but also vulnerable to manipulation by politicians who can speak to this narrative. A romantic view of the collapsed Ottoman Empire continues to shape how Turks view their place in the world today, so understanding this past is essential to understanding modern Turkey.

When compared with the foreign policies of his Ottoman and Turkish predecessors, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s approach to global and regional affairs represents both continuity and change. The Ottoman Westernization that began in the early nineteenth century was a strategic project driven by awareness of the state’s weakness. To revive the empire’s greatness, the sultans decided to copy institutions of statecraft from European global powers. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who established modern Turkey in 1923, further embraced this model, as did his successors. This trend continued after World War II, with Ankara turning toward Europe and the United States. While waiting for their great-power status to return, these late sultans and early presidents often allied with Western powers—with Britain through much of nineteenth century against Russia, with France through much of the interwar period against fascist Italy, and with the United States after World War II against the Soviet Union.

Erdogan has picked a more unorthodox model, however. His goal is to make Turkey great as a standalone power, not as a nation that simply relies on the West. Accordingly, his foreign policy has not been monolithic. When he first came to office in 2003, he felt cornered by Turkey’s secularist establishment, including the military. He therefore sought to be a better version of his Kemalist predecessors, promoting more internationalist, pro-American, and pro-EU policies. For instance, his early initiatives included attempts to unify Cyprus and normalize ties with Armenia.

That period came to an end by 2011, after Erdogan defanged the military, passed a series of laws placing the judiciary under his control, and began undermining his opponents—with help from the Gulen movement, his ally at the time. No longer boxed in by the secularists, he launched a new set of global and Middle Eastern initiatives aimed at reviving Turkey’s Ottoman-era power, with the region-wide “Arab Spring” uprisings setting the stage.

Yet this policy failed, primarily because Ankara ignored the role of “historical antibodies” in the Middle East—Erdogan did not realize that many Arabs, like many Greeks, still view Turkey quite negatively as their former colonial overlord. Moreover, Ankara wound up supporting just one actor during the Arab Spring: the Muslim Brotherhood. When the group lost influence in Egypt and other countries, so did Erdogan. Turkey’s support for the Syrian opposition backfired as well, putting it at odds with Russia and Iran.

Erdogan has tried to offset some of these losses in recent years, forcing Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu to resign in 2016 and restoring ties with Iraq and Israel. Nevertheless, Turkey is still isolated from most of the Middle East, with the exception of Qatar. Its ties with Washington have been zigzagging, and it can no longer rely on its traditional friends in the West, leaving the country exposed to threats from Moscow.

To alleviate these risks, Erdogan has entered into ad hoc deals with Russia, ranging from Syria policy to the purchase of S-400 air defense systems. President Vladimir Putin has been particularly responsive to these overtures since the failed Turkish coup of 2016, but his current courtship is serving the same purpose as Russian hostility did in the past: to bully Ankara. Erdogan has also built important relationships in Eurasia and Africa, however, so if Turkey’s economy recovers soon, he may be able to continue his recent approach while leveraging Moscow and Washington against each other.

AMANDA SLOAT

The current U.S.-Turkey relationship is marred by longstanding, accumulated grievances. Ankara takes issue with Washington’s refusal to extradite cleric Fethullah Gulen, whom Turkish officials claim was behind the 2016 coup attempt. They are also wary of U.S. cooperation with the People’s Defense Units (YPG), the Kurdish group that controls large parts of north Syria. For their part, U.S. policymakers are increasingly questioning whether Turkey is a reliable partner given its democratic backsliding, its decision to purchase S-400s from Russia, its delay in joining the campaign to defeat the Islamic State, and other factors.

Looking back, Washington was quite optimistic when Erdogan first rose to power and took steps to modernize Turkey’s economy, democracy, and bureaucracy. This sentiment was echoed in Brussels with the start of EU accession talks. Yet Turkey’s ties to the West have continuously deteriorated over the past decade, with each side trying to “muddle through” in order to maintain relations without resolving their grievances. Ankara is unlikely to link back up to the West anytime soon, so restoring relations to where they were in Erdogan’s early years is not in the cards right now.

MOLLY MONTGOMERY

Misconceptions about American policymaking make it difficult for Turkey to understand the U.S. government’s behavior on issues like Gulen’s extradition. As power is consolidated in Ankara, it becomes easier for Turkish officials to believe that Washington operates in the same fashion, and to see a single thread of intentionality behind discrete U.S. actions.

Similarly, Washington often fails to understand the drivers of Turkish foreign policy, including how the country’s national identity and history shape Erdogan’s decisions. His foreign policy is both a reaction to Kemalism and a conscious reassertion of Turkey’s place as a Muslim and Middle Eastern power.

In addition to tensions over Gulen, the YPG, and the S-400s, Washington has taken issue with Ankara’s handling of human rights, democracy, and rule of law since the attempted coup. These concerns have not yet been resolved, and are unlikely to be dealt with under Erdogan. Until these problems are fixed, there will be no genuine relinking between Turkey and the West. Yet Ankara’s East-West balancing act has become increasingly precarious, and the consequences of falling would be grave, potentially forcing Turkey to fold under Russia.

TOMASZ HOSKINS

A critical lesson for policymakers is that they cannot predict where things are going in Turkey until they know where they came from. The country’s rich history and often-contentious East-West relations are crucial to understanding its current politics—and to understanding the Middle East as a whole. There is a great line in Dr. Cagaptay’s book about the “in-between-ness” of modern Turkey: “From the East, Turkey looks like a Western country, and from the West, it looks like an Eastern country.” This dynamic lies at the center of how Ankara relates with its neighbors and views its place in global politics. Erdogan’s Empire provides a comprehensive education on the Turkish leader that was previously missing from the scholarly and policymaking worlds.

This summary was prepared by Deniz Yuksel. The Policy Forum series is made possible through the generosity of the Florence and Robert Kaufman Family.