Washington should use the State Department's upcoming annual "Trafficking in Persons" report to amplify international calls for strategic Persian Gulf partners to reform their expatriate labor practices.

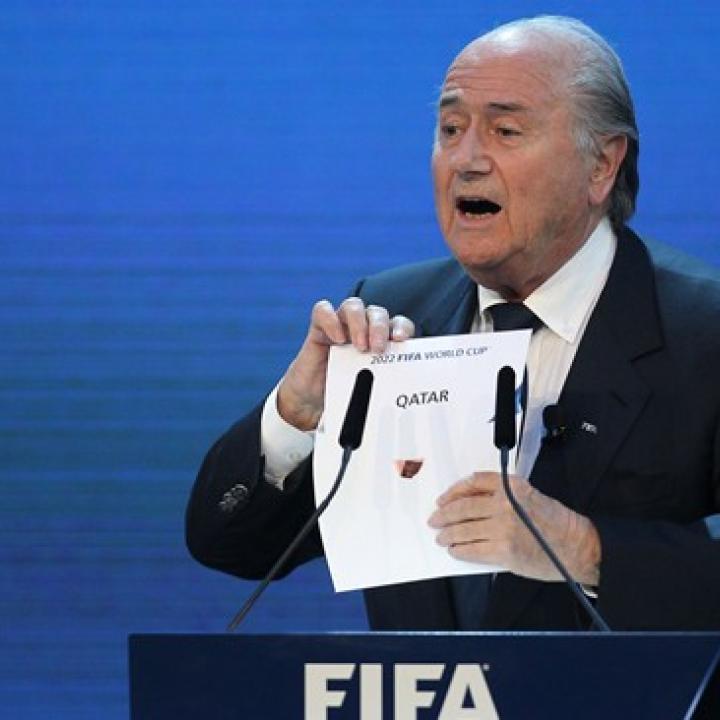

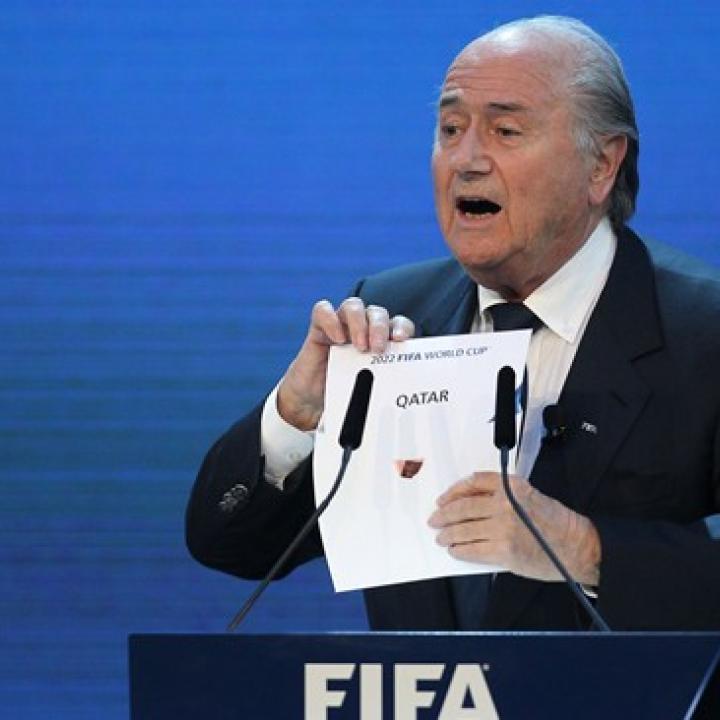

Last week's reports that the 2022 FIFA World Cup could be moved from Qatar to the United States in connection with corruption allegations came at an awkward moment, as the quadrennial games began in Brazil. In light of these reports, the other irrationalities surrounding the choice of Qatar as host -- including the fact that local temperatures in the small Gulf state average 106 degrees during the World Cup months of June and July, and that all of Qatar's 250,000 current citizens could not fill the eight stadiums being built for the games -- are taking a back seat to the corruption problem.

Yet one of the most important issues regarding Qatar's selection remains how the country intends to build the necessary infrastructure and otherwise prepare for the event: by relying on hundreds of thousands of expatriate workers living and working under often-abusive conditions. However the corruption charges play out, Washington should build on current momentum in the international community to encourage expatriate labor reform measures in Qatar and other Gulf states.

EXPATRIATES IN THE GULF

Qatar is home to the largest proportion of noncitizens relative to citizens in any country in the world: foreigners make up 88 percent of its 2.1 million population. To one degree or another, this phenomenon is prevalent across the six monarchies in the Arabian peninsula. In the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, foreigners also make up significant majorities of the populations, about 80 and 70 percent respectively. In Bahrain, they make up approximately 55 percent. In Saudi Arabia and Oman, the figure is around 30 percent. In no other region of the world do citizens constitute such a small proportion of the population as in these Gulf countries, according to World Bank estimates. And in many cases, the foreign workers in these states are asked to perform their duties under internationally illegal circumstances.

Recent revelations of poor foreign labor conditions in Qatar and the UAE -- home to the glossy cities of Dubai and Abu Dhabi -- have underscored how foreign workers sometimes live and work in situations where sufficient food is not provided, housing is squalid, working hours are unusually long, wages are decreased or withheld altogether for months at a time, and, most chillingly, changing jobs or leaving the country is prohibited, in a situation akin to forced labor. To be sure, many expatriates in the Gulf do not experience these problems, such as the various foreigners who serve as skilled professionals in government ministries, the oil sector, and private businesses. The bulk of those subjected to such conditions are unskilled migrants primarily from poor countries in South and Southeast Asia, with construction and domestic workers particularly vulnerable to abuse.

SYSTEM DRIVERS

A major driver of the Gulf foreign labor system are the wealthy and powerful members of the business elite and other local businessmen, including important government allies. Gulf nationals and international partners head the companies with which Gulf governments and other private firms contract, making tremendous financial gains by employing foreign labor inexpensively. Gulf and foreign recruitment agencies also profit by providing the required local "sponsorship" of foreign workers, including travel, visa, and other logistical arrangements. Against this backdrop, Qatari businessmen responded with deep concern to last month's announcement that the government intended to reform its expatriate labor law, in part by scrapping the requirement for a sponsor's approval to leave the country and increasing fines for sponsors who confiscate worker passports. The business community emphasized that this would allow workers to abscond from the country with debts owed to sponsors and employers.

Qatar and the UAE have made widespread efforts to reform their foreign labor practices in recent years, yet they and other Gulf governments have also enabled the current system. The Qataris and Emiratis in particular have sought to boost their political and economic might with attention-grabbing national projects, international commercial and other investments, and, in Qatar's case, unusual political liaisons and alliances. Qatar's lobbying campaign to host the World Cup is a case in point, and represents part of Doha's effort to build prestige and business through sponsorship of international sport.

Another driver of Gulf labor problems is the widespread local disdain toward expatriate workers. Beyond human-rights activists and other advocates for noncitizens, there is little popular interest in reforming the sponsorship system to advance foreign worker entitlements. Domestic concern about the social, cultural, and political implications of empowering extraordinary numbers of non-Arab migrants, or even expatriate Arabs who are not from the Gulf monarchies, helps fuel this attitude. In December 2012, a rare public opinion survey conducted in Qatar and financed by Qatar University found that nearly 90 percent of the citizens surveyed did not wish to see the sponsorship system weakened, with 30 percent supporting changes that would make foreign workers even more dependent on their sponsors.

U.S. POLICY

Gulf governments are sensitive and reactive to international criticism of their foreign labor laws and practices. For example, when Qatar's Interior and Labor Ministries announced the previously mentioned labor reforms on May 14, they were apparently responding to pressure from international rights organizations, press reporting, and other sources. And on May 18, when the New York Times ran a story on expatriate labor conditions linked to the construction of New York University Abu Dhabi, the international version of that day's edition was not published in the UAE; ten days later, the country's Foreign Ministry issued an extensive report on expatriate labor law reforms in recent years.

To be sure, announcements about reforms do not necessarily indicate actual structural reforms -- for example, the Qatari proposals publicized last month must still be passed by the country's Shura Council (an advisory legislative body) and other government departments, and they do not include minimum wage requirements or address basic working and living conditions. Yet because Gulf governments' attention to poor foreign labor conditions appears driven by an interest in protecting their international reputation, Qatar, the UAE, and other regional states that are hosting major international events in the next decade are now captive audiences to international calls for reform on this issue.

Accordingly, Washington should use the State Department's annual "Trafficking in Persons" report, scheduled to be released this month, to bolster the push for such reform. This important report -- which details expatriate labor conditions, laws, and practices worldwide and is the department's self-described "principal diplomatic tool to engage foreign governments" in advancing reform on such issues -- carries special potential to advocate for change in the Gulf.

Lori Plotkin Boghardt is a fellow in Gulf politics at The Washington Institute.