- Policy Analysis

- Articles & Op-Eds

Gulf De-escalation and Hedging in the Shadow of US Retrenchment

Also published in Caravan

Although any decrease in tensions is welcome, Washington should be concerned that regional rapprochement is being driven by diminished confidence in the United States.

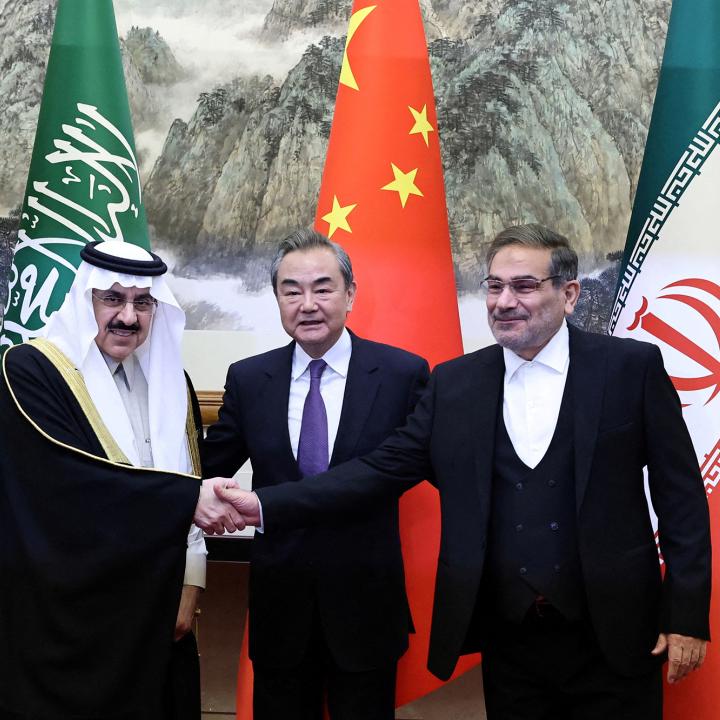

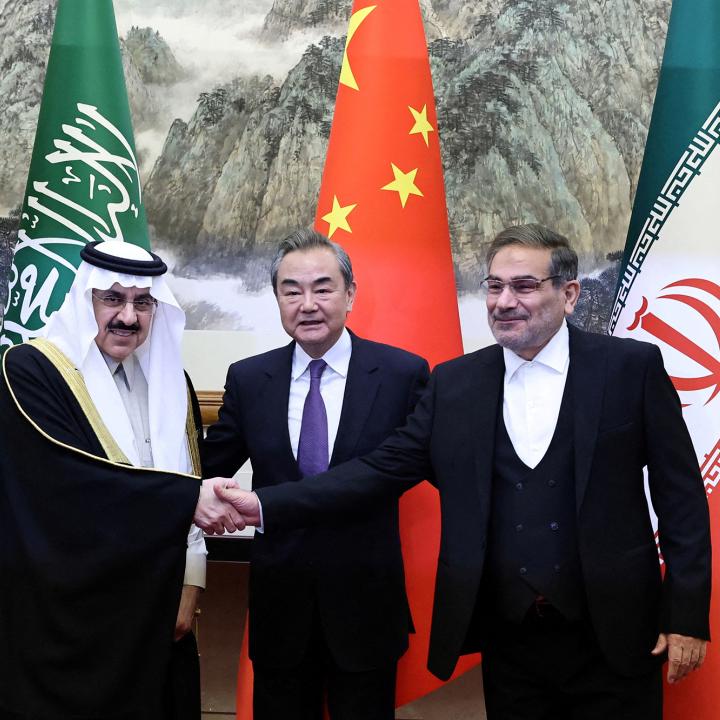

Seven years after ties were severed, the April 2023 China-brokered diplomatic rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran came as a shock to Washington. Even US intelligence agencies were surprised. Indeed, CIA director Bill Burns told Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that the US was “blindsided” by the agreement. Despite being caught unaware, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan nevertheless described the understanding as “not fundamentally averse to US interests,” which include the promotion of “de-escalation” in the Gulf.

De-escalating tensions with Iran has been a policy priority for the Biden Administration since day one. Inauguration signaled the end of the Trump-era “maximum pressure campaign” against Iran. Initially, the new Administration’s efforts focused on intensive diplomacy to cajole a recalcitrant Tehran to re-enter the 2015 JCPOA nuclear deal terminated by Trump. More recently, Washington has aimed lower, offering to release billions in Iranian frozen assets in return for Iran halting progress on enrichment—a critical step toward building a nuclear weapon—and a pledge not to murder Americans.

Notwithstanding the perquisites in the Biden Administration offer, Tehran has shown little interest in lowering the temperature with Washington. Increasingly, however, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have been determined to pursue detente with Iran and other adversaries, to de-escalate regional tensions. This shift—from confrontation toward aspirational “good neighborliness” (in the words of Saudi and Emirati officials) with Iran and other regional foes—occurred for several reasons.

First, confrontation wasn’t working. Not only had Riyadh’s efforts to end its costly war in Yemen against the Iranian-backed Houthi militia stalled, the group was targeting the UAE. At the same time, Iran continued to seize vessels in the Arabian Gulf, and threatened to itself attack the Emirates militarily. At the same time, the Biden Administration’s more conciliatory approach to Iran—which included the de-listing of the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, a lenient attitude toward sanctions enforcement, and unbridled enthusiasm for negotiations—neither reinforced nor supported the inimical policies of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi toward Iran.

Second, and particularly for Saudi Arabia, tensions with Iran were a distraction from domestic priorities. Riyadh’s priority is the implementation of Vision 2030, a highly ambitious development plan focused on diversifying the economy and reforming the social milieu. Among other things, the plan seeks to build a tourism industry beyond the Haj pilgrimage and to encourage the re-location of regional multinational corporate headquarters to the kingdom. The ongoing cold war with Iran and the hot war in Yemen complicated the execution of the Vision.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Saudi and the UAE sought a rapprochement with Iran because they had lost confidence in the US military commitment to its regional partners. Specifically, over time, a series of incidents and developments led Gulf partners to question the credibility of Washington’s implicit security guarantees. The signing of the JCPOA—which consecrated Iranian uranium enrichment—and President Obama’s subsequent musing in The Atlantic that the Saudis needed to “share the neighborhood” with Iran—were unsettling. Skepticism grew with the subsequent retrenchment of US troops and redeployment of equipment from the Arabian Peninsula, and Trump’s lack of kinetic response to high-profile attacks in 2019 on Aramco’s Abqaiq facility and the downing of a RQ-4A Global Hawk drone over the Gulf. More recently, in January 2022, the UAE was irritated by what it perceived as a lackluster Biden Administration response to a Houthi missile and drone attack on the capital, a barrage Emiratis say was their “9-11.”

The Trump Administration’s 2020 targeted killing of Iranian Revolutionary Guard commander Qassem Soleimani temporarily re-inspired Gulf confidence in Washington’s willingness to use force against Iran, but the approach, for better or worse, was not sustained. Like Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s expanding outreach to Beijing, the move toward rapprochement with Iran was indicative of a hedging strategy.

But the rapprochement and efforts to achieve regional de-escalation haven’t only been limited to Iran. In tandem with this Iran outreach, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates have worked to mitigate other tensions in the area. One separate but related effort on this front concerns the reintegration of Syria into the Arab system. Over the past year, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have driven an initiative to politically reintegrate and rehabilitate the Bashar Assad regime, which since 2011 and the brutal suppression of a popular uprising, has largely been treated regionally and internationally as a pariah.

At one time, perhaps, the decision to reactivate Damascus’ suspended participation in the Arab League might have required a consensus vote among the 22 member-states. In May 2023, only 13 states’ representatives showed up in Cairo to vote in favor of Syria’s return.

While the Emirates had in recent years initiated some modest contacts with Damascus, until lately, Riyadh appeared opposed to ending the isolation of Syria. What changed? First, Washington stopped dissuading its partners from engaging Damascus and accepted the end of Syria’s isolation as a fait accompli. Saudi Arabia also likely understood that the re-embrace of Assad would be taken as a goodwill gesture by Tehran, which has maintained a strategic partnership with Syria for nearly four decades. Of course, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi also hoped, unrealistically, that Syria’s reintegration might encourage the regime to end its prolific export of captagon, the amphetamine of choice in the region.

Beyond Syria, these states looked to bury the hatchet with Turkey, another longtime rival. Relations with Ankara under President Recip Tayyeb Erdogan, who has been in power for nearly 20 years, had been difficult for some time, but reached a nadir during the 2017-2021 Gulf Rift, when Gulf states, led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE sought to boycott Qatar for, among other things, supporting the Muslim Brotherhood. During the rift, Erdogan’s Turkey—another supporter of the MB—was a key ally of Qatar, enabling the small peninsula state to survive extreme pressure. Turkey also backed a different side than the UAE in the Libya civil war and was at odds with Egypt, a close partner and client of Saudi Arabia.

Last year, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi started to put aside their animosity toward Ankara and embraced Erdogan. In recent months, these states have provided billions in aid and signed enormous trade deals and defense procurement agreements to shore up the shaky Turkish economy and bolster the president’s elections campaign.

To be sure, Ankara has already benefitted greatly from its reconciliation with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. It’s less clear, however, how the understandings with Tehran and Damascus will pan out. The Assad regime remains uncooperative and is unlikely to ever submit to the precepts of UN Security Council Resolution 2254, which stipulates political transition. It’s equally improbable that the regime will transition away from its status as a narco-state and curtail its distribution of captagon throughout the region. How the diplomatic rapprochement with Tehran will impact the theocracy’s behavior—and that of its proxies—also remains to be seen.

Even before the formal agreement was reached in April, a fragile truce had been secured in Yemen. The rapprochement with Iran could bolster chances for a longer-term ceasefire, and even, perhaps, a formalized peace agreement between the Houthis and the Saudi-led coalition. To date, however, Iran’s renewed diplomatic ties with Saudi Arabia and the UAE have not de-escalated tensions in Arabian Gulf waters. Lately, in fact, tensions have spiked as Tehran has stepped up its efforts to seize oil tankers. Meanwhile in Iraq, Iranian-backed militias known as the Popular Mobilization Units or the Hashd al Sha’bi—which launched drone attacks on Saudi Arabia in 2019 and 2021—are gaining more power and influence.

In the short term, while renewed diplomatic ties may insulate Saudi Arabia and the UAE from direct attack by Iran and/or its proxies, they will not constrain Tehran from pursuing other problematic policies that challenge these states’ regional equities. Even so, given the low expectations, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi might consider this nominal de-escalation to be a success. For the Biden Administration, this slight decrease in tensions between the parties is a welcome development, in spite of it paradoxically coinciding with increased deployments of US troops and military hardware to the Gulf. The concern is that the rapprochement occurred, in large part, due to diminished confidence in Washington.

David Schenker is the Taube Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of its Rubin Program on Arab Politics. This article was originally published on the Hoover Institution website.